History of the Second World War (60 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

THE BATTLE OF THE CORAL SEA

The Japanese ground and air forces for the first move assembled at Rabaul in New Britain, and the naval forces at Truk in the Caroline Islands, a thousand miles to the north. Behind the amphibious groups destined for the two invasions lay a carrier striking force ready to beat off any American intervention. It comprised the carriers

Zuikaku

and

Shokaku

, with an escort of cruisers and destroyers, and carried 125 naval aircraft (42 fighters and 83 bombers). A further 150 aircraft at Rabaul could aid it.

American Intelligence, the Allies’ chief advantage, had discovered the main threads of the Japanese plan, and Admiral Nimitz sent all his available forces southward — the carriers

Yorktown

and

Lexington

from Pearl Harbor, with 141 aircraft (42 fighters, 99 bombers), and two groups of cruisers to escort them. (The two other American carriers,

Enterprise

and

Hornet

, returning from their part in the Tokyo raid, were also ordered to hurry down to the Coral Sea, but arrived too late for the battle.)

On May 3 the Japanese landed on Tulagi and took that island unopposed — as the small Australian garrison, forewarned, had been withdrawn. At that moment the

Lexington

was refuelling at sea while the

Yorktown

under Rear-Admiral Fletcher was farther away from the scene. But the next day it launched a number of strikes when about 100 miles distant from Tulagi. These had little effect beyond sinking a Japanese destroyer. The

Yorktown

was fortunate in escaping retaliation. For the two Japanese carriers had been sent to deliver a handful of fighter planes to Rabaul — sent off the scene merely to save an extra ferrying mission. It was the start of a series of mistakes or misunderstandings on both sides from which the Americans eventually profited on balance.

Admiral Takagi’s carrier group now came south, passing to the east of the Solomons and round into the Coral Sea, hoping to take in rear the American carrier force. Meanwhile the

Lexington

had joined the

Yorktown

and the two were steering north to intercept the Japanese invasion force that was on the way to Port Moresby. On May 6 — the black day of Corregidor s surrender — the opposing carrier groups searched for one another without making contact, although at one time they were only seventy miles apart.

Early on the 7th the Japanese searching planes reported that they had spotted a carrier and a cruiser, whereupon Takagi promptly ordered an all-out bombing attack on the ships, and speedily sank both. But, actually, they were only a tanker and escorting destroyer, so that time and effort were wasted. That evening Tugaki tried another and lesser strike, but the result was that twenty of the twenty-seven planes he employed were lost. Meanwhile Fletcher’s carrier aircraft, likewise led astray by a false report, expended their effort in an attack upon the close-covering force of the Port Moresby invasion. In this stroke they sank the light carrier

Shoho,

and did so in ten minutes — one of the quickest sinkings on record in the entire war. A more important effect was that the Japanese were led to postpone the invasion and order their force to turn back. It was an ironical benefit from the mistake of attacking the wrong ship. It was, also, one of several blind shots that day.

On the morning of May 8 the two opposing carrier forces at last came to grips. The two sides were closely matched, the Japanese having 121 aircraft and the Americans 122, while their escorts were almost equal in strength — four heavy cruisers and six destroyers on the Japanese side, five heavy cruisers and seven destroyers on the American side. The Japanese, however, were moving in a belt of cloud while the Americans had to operate under a clear sky. The primary consequence of this was that the carrier

Zuikaku

escaped attention. The

Shokaku,

however, suffered three bomb-hits and had to be withdrawn from the battle. On the other side, the

Lexington

suffered two torpedo-hits and two bomb-hits, and subsequent internal explosions compelled the abandonment of this much cherished ship — which sailors called the ‘Lady Lex’. The nimbler

Yorktown

escaped with only one bomb hit.

In the afternoon, Nimitz ordered the carrier force to withdraw from the Coral Sea — and the more readily as the threat to Port Moresby had vanished for the time being. The Japanese also retired from the scene, in the mistaken belief that both the American carriers had been sunk.

In absolute losses the Americans came off slightly better in aircraft, seventy-four compared with over eighty, while their loss in men was only 543 compared with over a thousand, but they had lost a fleet carrier whereas the Japanese had lost only a light carrier. More important, the Americans had thwarted their enemy’s strategic object, the capture of Port Moresby in New Guinea. And now by a superiority in technical achievement they managed to repair the

Yorktown

in time for the next stage of the Pacific conflict, whereas neither of the two Japanese carriers in the Coral Sea fight could be got ready for use in the second and more decisive fight.

The Battle of the Coral Sea was the first in history fought out between fleets that never came in sight of one another, and at ranges that had been extended, from the battleship’s extreme limit of about twenty miles, to a hundred miles and more. A greater repetition was soon to follow.

THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY

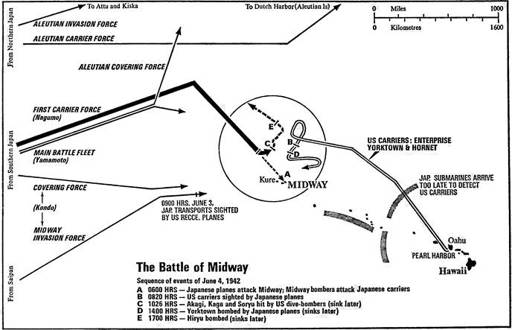

Imperial General Headquarters in Japan had already set this next stage going by its order of May 5. The plan produced by the Combined Fleet staff was extraordinarily comprehensive and elaborate, but lacking in flexibility. Almost the entire Navy was to be used in the operation. The total of some 200 ships included 8 carriers, 11 battleships, 22 cruisers, 65 destroyers, 21 submarines. They were assisted by more than 600 aircraft. Admiral Nimitz could scrape together only 76 ships, and of these a third, belonging to the North Pacific Force, never came into the battle.

For the main, the Midway operation, the Japanese employed (1) an advanced submarine force, patrolling in three cordons, and intended to cripple American naval countermoves; (2) an invasion force under Admiral Kondo of twelve escorted transports, carrying 5,000 troops, with close support by four heavy cruisers, and more distant cover from a force comprising two battleships, one light carrier and a further four heavy cruisers; (3) Nagumo’s First Carrier Force of four fleet carriers — carrying over 250 planes — escorted by two battleships, two heavy cruisers and a destroyer screen; (4) the main battle fleet under Yamamoto, comprising three battleships, with a destroyer screen, and one light carrier. One of the battleships was the recently built giant, the

Yamato

, of 70,000 tons and mounting nine 18-inch guns.

For the Aleutians operation the Japanese allotted (1) an invasion force of three escorted transports, carrying 2,400 troops, with a support group of two heavy cruisers; (2) a carrier force of two light carriers; (3) a covering force of four older battleships.

The battle was to open in the Aleutians, with air strikes against Dutch Harbor on June 3, followed by landings at three points on the 6th. Meanwhile, on the 4th, Nagumo’s carrier planes were to attack the airfield on Midway, and next day Kure Atoll (sixty miles to the west) was to be occupied for a seaplane base. On the 6th, cruisers would bombard Midway, and the troops be landed, the invasion being covered by Kondo’s battleships.

The Japanese expectation was that there would be no American ships in the Midway area until after the landing, and their hope was that the U.S. Pacific Fleet would hurry northward as soon as news came of the opening air strike in the Aleutians. That would enable them to trap it between their two carrier forces. But in pursuing this strategic aim, the destruction of the American carriers, the Japanese handicapped themselves by their tactical arrangements. Because of the favourable moon conditions of early June, Yamamoto was unwilling to wait until the

Zuikaku

had replaced her aircraft losses in the Coral Sea and could reinforce the other carriers. As for the eight available carriers, two were sent to the Aleutians and two more were accompanying battleship groups. At the same time, fleet movements were tied to the speed of slow troop transports. Moreover, it is hard to see the point of a diversionary move to the Aleutians if the Japanese main object was the destruction of the American carriers, and not merely the capture of Midway. Worst of all, by committing themselves to the capture of a fixed point at a fixed time, the Japanese forfeited strategic flexibility.

On the American side, Admiral Nimitz’s main worry was the Japanese superiority of force. Since the Pearl Harbor disaster he had no battleships left, and after the Coral Sea battle only two carriers fit for action, the

Enterprise

and the

Hornet

. But by an astonishing effort they were increased to three through the repair of the

Yorktown

in two days instead of an estimated ninety.

Nimitz’s one great, and offsetting, advantage was the superiority of his means and supply of information. The three American carriers, with their 233 planes, were stationed well to the north of Midway, so as to be out of sight of Japanese reconnoitring planes, while they could count on getting early word of Japanese movements from their long-range Catalinas based in Midway. Thus they hoped to make a flank attack on the Japanese forces. On June 3, the day after the carriers were in position, air reconnaissance sighted the slow-moving Japanese transports 600 miles west of Midway. Gaps in the search patterns flown by Japanese aircraft allowed the American carriers to approach unseen, from the north-east. They were also helped by the belief of Yamamoto and Nagumo that the U.S. Pacific Fleet would not be at sea.

Early on June 4, Nagumo launched a strike by 108 of his aircraft against Midway, while a further wave of similar size was being prepared to attack any warships sighted. The first wave did much damage to installations on Midway, with little loss to itself, but reported to Nagumo that there was need for a second attack. Since his own carriers were being bombed by planes from Midway, he felt that there was still need to neutralise the island’s airfields, so ordered his second wave to change from torpedoes to bombs for this purpose, as there was still no sign of the American carriers.

Shortly afterwards, a group of American ships was reported about 200 miles away, although it was at first thought to consist only of cruisers and destroyers. But at 0820 came a rather more precise report saying that the group included a carrier. This was an awkward moment for Nagumo, as most of his torpedo-bombers were now equipped with bombs, and most of his fighters were on patrol. He had, also, to recover the aircraft returning from the first strike at Midway.

Nevertheless, the change of course north-eastward which Nagumo made on receiving the news helped him to avoid the first wave of dive-bombers despatched against him from the American carriers. And when three successive waves of torpedo-bombers — relatively slow machines — attacked the Japanese carriers between 0930 and 1024, thirty-five of the forty-one used were shot down by the Japanese fighters or anti-aircraft guns. At that moment the Japanese felt that they had won the battle.

But two minutes later thirty-seven American dive-bombers from the

Enterprise

(under Lieutenant-Commander Clarence W. McClusky) swooped down from 19,000 feet, so unexpectedly that they met no opposition. The Japanese fighters that had just shot down the third wave of torpedo-bombers had no chance to climb and counterattack. The carrier

Akagi,

Nagumo’s flagship, was hit by bombs which caught its planes changing their own projectiles and exploded many of the torpedoes, compelling the crew to abandon ship. The carrier

Kaga

suffered bomb-hits that destroyed her bridge and set her on fire from stem to stern; she eventually sank in the evening. The carrier

Soryu

suffered three hits with half-ton bombs from the

Yorktown’s

dive-bombers, which now arrived on the scene, and was abandoned within twenty minutes.

The only still intact fleet carrier, the

Hiryu,

struck back at the

Yorktown

and hit her so badly in the afternoon as to cause her abandonment — she was weakened by the damage, hastily repaired, that she had suffered in the Coral Sea battles. But twenty-four American dive-bombers, including ten from the

Yorktown,

caught the

Hiryu

in the late afternoon and hit her so severely that she had to be abandoned in the early hours of the 5th, and sank at 0900 hours.

This battle of the Fourth of June saw the most extraordinarily quick change of fortune known in naval history, and also showed the ‘chanciness’ of battles fought out in the new style by long-range sea-air action.

Admiral Yamamoto’s first reaction to the news of the disaster to his carrier force was to bring up his battleships, while bringing back his two light carriers from the Aleutians — still in the hope of fighting a sea-battle more in the old style to restore the prospect. But the subsequent news of the loss of the

Hiryu,

and Nagumo’s gloomy reports, led to a change of mind, and early on the 5th Yamamoto decided to suspend the attack on Midway. He still hoped to draw the Americans into a trap, by withdrawing westward, but was foiled by the fine combination of boldness with caution shown by Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, who commanded the two American carriers

Enterprise

and

Hornet

in this crucial battle.