History of the Second World War (61 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

Meantime, the Japanese attack on the Aleutian Islands in the North Pacific had been delivered as planned early on June 3, when the two light carriers allotted for the operation launched twenty-three bombers, with twelve fighters, against Dutch Harbor. It was too small a force for serious effect except by luck, and did little damage, as cloud obscured the ground. A repetition next day, in clearer weather, achieved some hits but nothing drastic. Then on June 5 the carriers were called southward to help in the main operation. On the 7th, however, the small seaborne force of Japanese troops landed on, and captured unopposed, two of the three islands — Kiska and Attu — which had been assigned as objectives. Japanese propaganda made the most of this minor achievement, to offset the crucial failure at Midway. Superficially, the capture of these points looked an important gain, as the Aleutian chain of islands stretching across the North Pacific lay close to the shortest route between San Francisco and Tokyo. But in reality these bleak and rocky islands, often covered in fog or battered by storms, were quite unsuitable as air or naval bases for a trans-Pacific advance either way.

In sum, the operations of June 1942 were a crushing defeat for the Japanese. They had lost in the Midway battle itself four fleet carriers and some 330 aircraft, most of which went down with the carriers, as well as a heavy cruiser — whereas the Americans lost only one carrier and about 150 aircraft. The dive-bombers had been the key weapon on the American side — in contrast, over 90 per cent of the torpedo-bombers had been shot down, while the large B.17 bombers of the Army had proved quite ineffective against ships.

Beside the basic strategic errors earlier mentioned, the Japanese also suffered from other handicapping faults of various kinds. Among ‘command’ faults was Yamamoto’s virtual isolation, on the bridge of the battleship

Yamato

, Nagumo’s loss of nerve, and the naval tradition that led Yamaguchi and other leaders to go down with their ships instead of seeking to recover the initiative. Nimitz, by remaining on shore, was able to keep an overall grip on the strategic situation, in contrast to Yamamoto.

Japanese troubles were multiplied by a string of tactical errors — the failure to fly sufficient search planes to spot the American carriers; lack of fighter cover at high altitude; poor fire precautions; striking with the planes of all four carriers, which meant that they had to recover and rearm their aircraft at the same time, so that there was a period when their carrier force had no striking power; steering towards the enemy when the changes were taking place, which gave the American planes the chance to locate Nagumo’s force more easily and to hit it before it could hit back or even defend itself with its fighters. Most of these faults could be traced to complacent overconfidence.

Once the Japanese had lost these four fleet-carriers, and their well-trained aircrews, their continued preponderance in battleships and cruisers counted for little. These ships could only venture out in areas that could be covered by their own land-based aircraft — and the Japanese defeat in the long struggle for Guadalcanal was principally due to lack of air control. The Battle of Midway gave the Americans an invaluable breathing space until, at the end of the year, their new ‘

Essex

’ class fleet carriers began to become available. Thus it can reasonably be said that Midway was the turning point that spelt the ultimate doom of Japan.

THE SOUTH-WEST PACIFIC AFTER MIDWAY

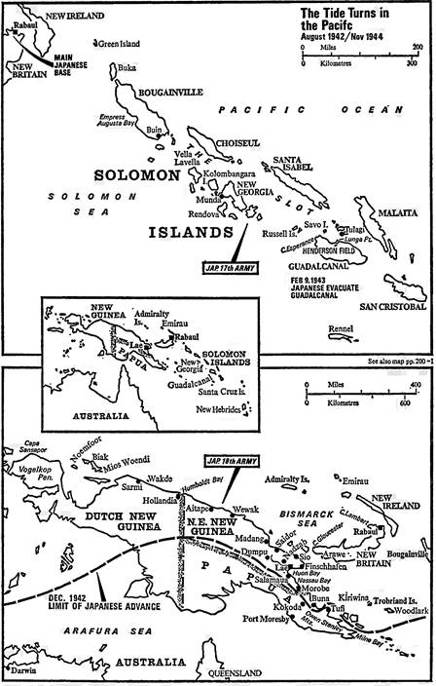

Even so, although the outcome of the Midway battle severely handicapped — and, indeed, curbed — the Japanese advance in the South-west Pacific, it did not halt it. While the Japanese could no longer use their fleet to press their advance, they still chose to continue it, and in a two-pronged way — in New Guinea, by overland attack across the Papuan Peninsula in the east of that vast island; and in the Solomons by a process of hopping from island to island, establishing airfields along the chain to cover successive short hops.

NEW GUINEA AND PAPUA

When the Japanese entered the war in December 1941, most of Australia’s operational forces were fighting with the British Eighth Army in North Africa — although they were to be recalled when the emergency developed. In New Guinea, so menacingly close to Australia itself, the only considerable force was one of brigade size posted at Port Moresby, the capital of Papua, on the south coast. The very small Australian garrisons on the north coast, as well as in the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomons, were withdrawn as soon as the Japanese approached. But it was considered essential to hold on to Port Moresby, because Japanese air attacks from there could have reached Queensland itself, on the Australian mainland. The Australian people were, naturally, sensitive to such a threat.

Early in March 1942, the Japanese, from Rabaul, had landed at Lae on the north coast of New Guinea, close to the Papuan Peninsula. But, as already related, their seaborne expeditionary force to capture Port Moresby was turned back in consequence of the otherwise indecisive Battle of the Coral Sea in May. Meanwhile General Douglas MacArthur had been appointed Allied Commander-in-Chief of the South-west Pacific area. And after the Battle of Midway early in June, the Allied position became much more secure, directly as well as indirectly, since most of the Australian troops had by now returned home, and new divisions were being formed, while the United States had placed two divisions and eight air groups in Australia. In Papua, too, Australia’s strength was increased to more than the size of a division — two brigades at Port Moresby, and a third at Milne Bay on the eastern tip of the peninsula, while two battalions were pushing forward over the Kokoda trail to Buna, on the north coast, with the aim of establishing an airbase there to provide cover for the planned amphibious advance by the Allies westward along the coast of New Guinea.

But on July 21 this move was forestalled, and the apparently fading Japanese threat revived, when the Japanese landed near Buna — with some 2,000 men — as part of their renewed attempt to capture Port Moresby, this time by overland attack. The Allies had a further shock when, on the 29th, the Japanese took Kokoda, nearly half way across the peninsula — and by mid-August, with a force built up to a strength of over 13,000 men, they were pressing the Australians back along the jungle track. But although the peninsula here was little more than a hundred miles wide, the trail had to cross the Owen Stanley Mountains, at a point 8,500 feet high, and the growing difficulties of supply across such difficult terrain — naturally worse for the attacking side — were multiplied by Allied air attacks. Within a month the Japanese advance was brought to a halt some thirty miles short of its objective. Meantime, a smaller Japanese force (of 1,200 men, reinforced to 2,000) had landed in Milne Bay on August 25, and succeeded in reaching the edge of the airstrip there after five days’ fierce fighting, but was then counterattacked by the Australians and driven to re-embark.

By mid-September MacArthur had concentrated in Papua the bulk of the 6th and 7th Australian Divisions, and an American regiment, ready to take the offensive. On the 23rd General Sir Thomas Blamey, the Australian Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Land Forces, South-west Pacific, arrived at Port Moresby to take control of the operations. His forces in their turn met fierce resistance as they strove to fight their way back to Kokoda, and on to Buna, but their difficulties of supply were eased by increasing use of air transport. By the end of October the Japanese were dislodged from the last of the three successive positions they had constructed near Templeton’s Crossing, at the top of the range, and on November 2 the Australians reoccupied Kokoda, reopening the airfield there. The Japanese tried to make a fresh stand on the Kumusi River, but their defence was overcome with the aid of bridging material dropped by air, and the flank threat of fresh Australian and American troops who were brought forward by air to the north coast.

Nevertheless the Japanese managed to make a prolonged final stand around Buna throughout December, and it was not until further Allied reinforcements had arrived, by sea and air, that the last pocket of Japanese resistance on the coast was liquidated, on January 21, 1943. In the six months’ campaign they had lost over 12,000 men. The Australian battle-casualties were 5,700 and the American 2,800 — a total of 8,500 — while they had suffered three times as many from sickness in the tropical damp-heat and malarial jungles. They had proved, however, that they could successfully fight the Japanese even in such appalling jungle conditions, and that air-power in all its varied forms provided a decisive advantage.

GUADALCANAL

The Guadalcanal campaign developed from the mutual, and natural, desire of General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz to exploit the Midway victory by a speedy change-over from the defensive to the counteroffensive in the Pacific. Their desire was backed by their respective chiefs in Washington, General Marshall and Admiral King, in so far as such an offensive could be reconciled with the grand strategy, agreed with the British, of ‘beat Germany first’. For any early counteroffensive the only feasible area was the South-west Pacific, and on that all were agreed. But a conflict of opinion arose, also quite naturally, as to who should direct and command the counteroffensive. Now that enemy pressure on the Hawaiian Islands, in the Central Pacific, had been not only relieved but removed, the Navy became all the more eager to play its full part in what basically had to be an amphibious operation. It was only with reluctance that Admiral King had accepted the policy of tackling Germany first and building up American strength in Britain for that purpose. British arguments against an early cross-Channel attack, in 1942, had caused Marshall to veer round towards the idea of giving the Pacific priority, and King was delighted to welcome such a change of view, even if it were no more than temporary — and unlikely to be endorsed by President Roosevelt as a definite change of policy.

But agreement about a changeover to the offensive in the South-west Pacific immediately sharpened the argument as to who should be in charge of it, and in the last part of June the debate became passionate. The outcome was a compromise, expressed in the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive of July 2, inspired by Marshall. The offensive was to be carried out in three stages, the first being the occupation of the Santa Cruz islands and the eastern Solomons, especially Tulagi and Guadalcanal. For this purpose the boundary between the zones was shifted, so that this area came under Nimitz, who would therefore conduct the first stage of the offensive. The second stage would be the capture of the rest of the Solomons, and of the New Guinea coast as far as the Huon Peninsula, just beyond Lae, while the third stage would be the capture of Rabaul, the main Japanese base in the South-west Pacific, and the rest of the Bismarck Archipelago — these two stages falling to MacArthur’s direction under the redistribution of zones.

The plan under this compromise did not please MacArthur who, immediately after the Midway victory, advocated a speedy and large-scale attack on Rabaul, confidently predicting that he could quickly capture it, with the rest of the Bismarcks, and drive the Japanese back to Truk (in the 700-miles-distant Caroline Islands). But he was brought to recognise that he could not hope to obtain the force he considered necessary — a marine division and two carriers, in addition to the three infantry divisions he already had. So the compromise three-stage plan was adopted — and took much longer to complete than any of the leaders had expected.

The Allies’ plan, for capturing the eastern Solomons, was forestalled — as it had been in Papua. On July 5 reconnaissance planes reported that the Japanese had moved some forces from Tulagi to the larger nearby island of Guadalcanal (ninety miles long and twenty-five miles wide), and were building an airstrip at Lunga Point (this later came to be called ‘Henderson Field’). The obvious danger of Japanese bombers operating from there caused an immediate reconsideration of American strategy, and Guadalcanal itself became the primary objective. With its backbone of wooded mountains, heavy rainfall, and unhealthy climate it was not a favourable objective for any campaign.

The overall strategic direction of the operation, under Nimitz, was entrusted to Vice-Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, the area C.-in-C., while Rear-Admiral Fletcher was in tactical command of it — he also controlled the three covering carrier groups built around the

Enterprise, Saratoga,

and

Wasp

respectively. Land-based air support came from Port Moresby, Queensland, and various island airstrips. The landing force, commanded by Major-General Alexander A. Vandegrift, comprised the 1st Marine Division and a regiment of the 2nd, totalling 19,000 Marines carried in nineteen transports, with escorts. No sign of the enemy was seen as the armada approached, and early on August 7 the air and naval bombardment opened, while the landings began at 0900 hours. By evening 11,000 Marines were ashore, and the airfield was occupied next morning; it was found to be nearly completed. The 2,200 Japanese on Guadalcanal, who were largely construction workers, had mostly fled into the jungle. On Tulagi, the Japanese garrison of 1,500 troops had put up a tougher resistance, and it was not until the second evening that they were overcome and wiped out, by the 6,000 Marines who had landed there.