Jessen & Richter (Eds.) (77 page)

Read Jessen & Richter (Eds.) Online

Authors: Voting for Hitler,Stalin; Elections Under 20th Century Dictatorships (2011)

290

S T E P H A N M E R L

success, local archival material gives us at least an idea of how widespread

this practice was.24 The data prove that threatening could be helpful. Until

the mid-1950s the risk of being repressed was greater, for prospects of

success became more promising afterwards, provided that this threat of

civil disobedience was connected to a concrete demand (Kozlov and

Mironenko 2005, 188). Felix Mühlberg documents that this type of threat-

ening was practiced in the GDR as well. In the context of housing condi-

tions, he even assigns the threats a certain “serial ripeness”.25

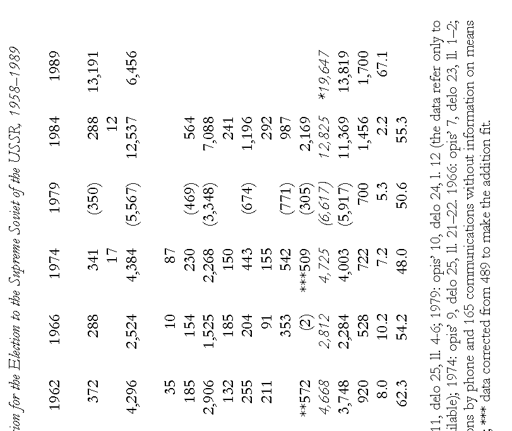

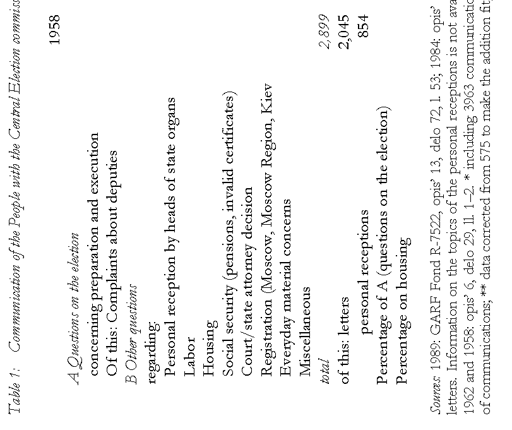

Data from 1958 to 1989 prove how widespread it was to address the

Central Election Commission for the election of the Supreme Soviet with

personal matters. People sent letters or used the offer of a personal recep-

tion. In 1989, it was also possible to contact the Commission by phone

(see table). Although one would have expected people to address the Cen-

tral Election Commission with questions regarding the pre-election cam-

paign or the balloting, the data reveal that the share of such questions was

only 8 to 10 per cent until 1966, and then decreased from 7 to 2 per cent

between 1974 and 1984. Only under the influence of

glasnost’

and the possibility of choosing between candidates for the first time, the interest in the

legal questions of voting increased significantly during the 1989 campaign,

reaching 67 per cent of the total communications.26 The bulk of

communication until 1984 consisted of requests related to personal wel-

fare, and was thus different from voter instructions during the pre-cam-

paign meetings. The significant rise in the total amount of communication

can obviously be explained by the fact that an ever-growing share of voters

understood that their requests actually had a chance of being accepted.27 It

——————

24 GAYO, Fond R-2513, opis’ 1, delo 197, lists the pre-election checking of complaints and petitions in the Yaroslavl’ election district 356 between January 26 and March 15, 1954. 2 out of 3 complaints on housing were decided positively, only one rejected, as the complainer had rejected the apartment assigned to him before. Other fulfilled petitions included providing a job, firewood, hospital treatment of the son, or the cleaning of a public room.

25 Mühlberg (2004, 238–41) cites a note to Honecker from December 8, 1988. Until the end of November 318 petitions were sent to the state council in connection with the local election. 78 writers threatened not to vote if their request was not fulfilled.

26 Cf. table, GARF, Fond R-7522.

27 See table and GARF, Fond R-7522. The reasons why in 1966 the total number went down to 2,800, returning to the 1962-level only in 1974 is not clear. The strong increase in the number of communications in 1984 may speak for a politicization, due to growing discontent with fulfilling the consumption promise. For 1989 the reason was different. This was the first election under Soviet rule allowing contesting candidates, and

E L E C T I O N S I N T H E S O V I E T U N I O N , 1 9 3 7 – 1 9 8 9

291

is not surprising that matters of housing conditions held top priority, with

an estimated share of 50 to 55 per cent of the overall communication. The

high share of complaints about court decisions or decisions of prosecutors,

clocking in at nearly 10 per cent, illustrate to what extent these questions

were of importance for the voters’ relationship to the state.28 As these

people used perfectly legal channels to tell the authorities about their con-

cerns, simultaneously reinforcing their acceptance of the paternalistic char-

acter of state power, I cannot agree with Thomas Bohn, who has inter-

preted these letters and the notes on the ballots as dissent.29

Part of the bargaining and communication on the official’s side was to

provide sufficient consumer products and supply sufficient goods for cele-

bration of election day as a holiday. In a report from the minister of trade,

Pavlov, to Khrushchev on December 18, 1957 the minister pointed out the

need to increase the supply of some everyday consumer goods then in

short supply, causing mass complaints by the people during 1957. He

asked the Central Committee to order an increase of production and to

import special goods, among them sugar, tea and plant oil, in direct con-

nection to the March 1958 election.30 In 1963 the Moscow City Executive

Committee addressed the head of the Council of Ministers, Kosygin, re-

questing him to release additional consumer goods from the state reserve

for Moscow’s supply on the day of the election of the Supreme Soviet of

the RSFSR. Kosygin reacted directly and gave the order with the hand-

written remark “urgent” to ensure the satisfaction of the Moscow voters

on election. Among the goods requested by the

Mossovet

were black caviar, television sets, washing machines, radios, meat, tobacco, cheese, and five

million razor blades.31 While Pavlov’s’ list in 1958 mostly consisted of basic

consumption goods, their special delivery to Moscow voters included a lot

of luxury goods.

——————

there was a growing interest among sections of the voters to uphold “democratic procedures” during the election.

28 See table. GARF, Fond R-7522, opis’ 11 (1984), delo 25, ll. 4, 5 and 12 reports that many writings were about how to appeal or protest against court verdicts or decisions of state security organs. Among “other questions”, at 2,056 letters, 16 per cent of the total, were requests to get a private car, a land parcel, and requests for environmental protection.

29 Cf. the contribution of Bohn in this volume.

30 RGAE, Fond 7971, opis’ 1, delo 2929, ll. 305–8.

31 RGAE, Fond 195, opis’ 1, delo 18, ll. 27–30, from February 7–8, 1963.

292

S T E P H A N M E R L

E L E C T I O N S I N T H E S O V I E T U N I O N , 1 9 3 7 – 1 9 8 9

293

Execution of the Vote: Facts and Political Discourse

Election day, usually a Sunday, served as a symbolic celebration of the

unity of subjects and ruler and had to demonstrate the cultural achieve-

ments of Soviet power. The district Party secretary was personally respon-

sible for the local arrangements to make all voters appear at the polling

stations and to vote for the candidate. In order to obtain his votes, he had

to present goods for bargaining in exchange. He attracted the voters by

organizing a public festival, satisfying them with a varied program of en-

tertainment: movie screenings highlighting the achievements of Soviet

power, children and veteran choirs, orchestra performances and other

cultural events, and last, but not least, with buffets selling sausages other-

wise unavailable in the state trade over long periods of the year. Sometimes

even alcoholic drinks were served. It was also obligatory to offer children’s

rooms in the polling station. Thus, for example the city Party committee of

Rybinsk reported on the RSFSR-Supreme Soviet election on March 4,

1963 that in this city of about 300,000 inhabitants, there were 135 concerts

performed, and 35 movies shown.32 Election day required extraordinary

security measures. Avoiding any form of protest was top priority. The local

Party secretary had to give updates thrice on election day: on the progress

of the voting, the atmosphere and special events.33

One report reads like another, notwithstanding whether it was written

in 1946 or 1984, whether in a polling district in the center of Moscow or a

remote national district. The primary function of these reports was to

prove the careful preparation of the day and to record the patriotic behav-

ior of the people. No report would forget to mention that the people

started to gather around the polling station during the night, patiently

queuing up in front of the station, waiting for its opening at 6am in the

morning. The standard narrative then mentioned the name of the young

person, proud to take part in the election for the first time, reciting a poem

praising the wise ruler in front of all people. This poem would be cited by

word in the report. Subsequently, a selection of other wordings of patriotic

——————

32 TsDNIY, Fond 7386, opis’ 5, delo 3, ll. 206–16. The Omsk

oblast’

Party Committee reported in 1974 that 1,636 buffets, 1,542 movie screenings, 713 concerts and 1,600

children’s rooms were organized (RGANI, Fond 5, opis’ 67 (1974), delo 97, ll. 34–35.

33 (Kozlov and Mironenko 2005, 186–212). On the planning of the election day, the distribution of responsibility and the obligations to report see GAYO, Fond R-2513, opis’ 1, delo 147 (1954).