Just 2 Seconds (12 page)

Authors: Gavin de Becker,Thomas A. Taylor,Jeff Marquart

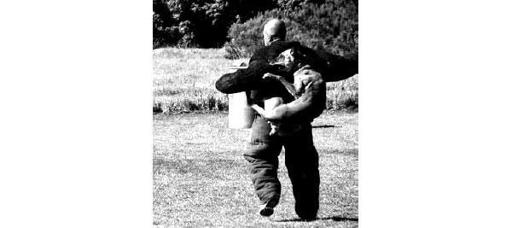

Photo by Gavin de Becker & Associates

To inoculate against a disease, a small dose of the disease is used. Similarly, to inoculate against a stressor

[?]

, we have to give a dose of the precise stress that protectors might experience in an attack -- and then have them prevail.

Our students are stung by the painful shots, their skin is broken, and the memory that's imprinted contains the experience of continuing to function effectively in the face of pain and injury.

Research indicates that people in attack situations can have sustained heart rates of higher than 200 beats per minute, so our students learn a lot about the destructive effects of increased heart rate. Consider that for the average person, when the heart rate reaches about 115, fine motor control begins to deteriorate, along with visual reaction time and judgment. Up around 145, substantial reductions in performance occur, some caused by the body's rerouting blood away from the muscles. Our Academy has exercises in which protectors under attack must perform actions requiring dexterity (unlocking a car door, for example). In early engagements, it's not uncommon for students to be incapable of even simple, familiar actions.

After just a couple of Simunition

(r)

engagements, student heart rates come down, allowing motor skills and judgment to be retained. Our experience has confirmed this reasonable assumption:

Attacks are more stressful for protectors than for attackers.

That's because attackers must be calm in order to achieve accuracy, and they must maintain at least the illusion of calm in order not to tip their intent too early. Their breathing is under control, and even at the Moment of Commitment, attackers can (and usually must) stay fairly still. Conversely, at that same moment, protectors need to move suddenly and quickly, compelling increased heart rate. Given this, stress inoculation training is all the more important to help prepare protectors to retain effectiveness during attacks.

Attack simulations and the use of Simunition

(r)

are, thankfully, gaining wider acceptance, but the type of Stress Inoculation training we are discussing next is not something you'll likely have read about elsewhere. Only our Academy is applying it.

Combat Stress Inoculation

The emergency situation that is far and away the most difficult to accurately simulate is close-quarters combat of the type one might experience in an attack. Hand-to-hand combat training at police and military academies typically involves someone playing a bad guy and "attacking" another participant. This method cannot be fully effective, because trainees always know that the role-playing instructor isn't going to injure them, and is, in fact, seeking to avoid doing injury. The student knows he is not likely to lose an eye or break a wrist during simulated fights. Accordingly, the experience doesn't trigger the same level of fear and stress as an actual violent encounter.

To accurately simulate combat, we developed an innovative use of attack-trained police dogs. Before the exercise begins the trainee has absolutely no idea what is coming, not even that a dog will be involved. During the first encounter, a dog is secured on a chain, and the trainee is placed just out of reach. The trainee is directed to remain in place and stand eye-to-eye taunting the viciously growling animal.

Photo by Gavin de Becker & Associates

Photo by Gavin de Becker & Associates

In the next encounter, the dog that the trainee has just been taunting is no longer chained, however the trainee is wearing bite-resistant clothing. The dog is ordered to attack with all it's got. Even though the powerful bites don't penetrate the skin, the trainee experiences the tension, grappling, wrestling, and aggressiveness of an actual violent attack -- because it is an actual violent attack. Having a dog latched onto one's arm -- or chest, or back -- trying with all its energy to pull you the ground and hurt you, convinces the body to go into its full defense mode.

These encounters with police dogs do much more than simulate violence -- they

are

violence. Trainees are aware throughout that every encounter is dangerous, and that the animal intends and is trying to do them harm. That's an experience impossible to achieve in conventional training.

When police dogs bite onto a jacket sleeve and find no resistance, or when they encounter a limb that goes limp, they are trained to bite elsewhere. For this reason, a trainee must, in effect,

feed

an arm to the attacking dog -- otherwise, he will be bitten elsewhere. This calls for courage, requiring a trainee to directly face the attacking animal, and to resist the impulse to turn and run.

Photo by Gavin de Becker & Associates

Trainees learn to keep moving the arm or leg the dog is biting; this keeps the dog from attacking elsewhere, but also keeps the dog agitated. Just when a trainee gets used to one dog, a new dog is introduced.

Our goal is to continue escalating the situation, adding ever more stress and uncertainty. The trainee is next placed in the back of a van, and then the dog is sent into the vehicle to attack in that claustrophobic environment.

Photo by Gavin de Becker & Associates

Next, the trainee is placed in a very small, pitch black building. The animal enters the building through a long tunnel, and then attacks the trainee from behind. The trainee has to exit the building with an attacking dog on his leg, arm, torso -- wherever the dog has clamped on.

Photo by Gavin de Becker & Associates

Graduates of this training are sworn to secrecy about the dogs so that upcoming academy students will not be aware of what's coming. We were concerned that the effectiveness would be reduced by advance knowledge -- but we've decided to include the information in this book because of its possible benefit to other protectors and organizations. We've learned that no matter what one might know in advance, people facing an angry and motivated attack dog will reliably react just as Nature has prepared them to: with fear and stress. Students overcome the natural impulse to run or retreat, and they learn to actually advance toward the danger ("feeding" an arm to the dog). To whatever degree they are stressed, so to that same degree will they be relieved and encouraged (literally inspired with courage) after prevailing through the exercise. Said one, "After you've fought with a few of those animals, grappling with a man is tame by comparison."

You Are the Predator

One of the most important truths you can bring with you into attack situations is the knowledge that you are the predator, not the prey. At the moment of attack, particularly a handgun attack, the attacker is not attacking you. In fact, from the Moment of Recognition onward, the reverse is true: The protector is the predator of the attacker. Why does this distinction matter so much? Because the way the body assigns its resources when you are predator is completely different from how the body responds when you perceive yourself as prey.

Bruce Siddle, author of

Sharpening the Warrior's Edge

and

Warrior Science,

tells us that "Comprehending the Predator vs. Prey mindsets is the key to successful 'operator' performance, and can be the secret to making the assassin miss."

If you perceive yourself as prey, your body is likely to throw you into debilitating stress reactions associated with an imminent threat to survival. Siddle explains: "In early man, these reactions played an important role when survival was threatened by a large predator: The body tuned out peripheral information, focused on the immediate threat, and increased blood flow to muscle groups that support gross motor skills (running, jumping, etc). Essentially, the stress reaction enhanced man's ability to become fast, quick, and strong when necessary -- but not without a cost to high level analytical processing and the ability to execute fine, complex, and precision motor tasks."

It's valuable to perceive yourself as predator at all times during a protective assignment, not just during an attack, and there's a particular challenge at the moment of attack: the inclination to say it isn't happening, which slows down a protector's arrival at the Moment of Recognition. Through training, protectors can learn to surrender to the reality of what is occurring. This doesn't mean surrender to the attacker -- but rather surrender to the situation, which is a strategy in itself. Surrendering to the situation lands you

in

the situation, as opposed to thinking about the situation. Landing in the present moment gets us out of our heads, where we tend to resist the present moment (e.g., I wish this weren't happening, this isn't fair, this is wrong, why did this happen, etc).

Attack simulation training is critically important so that protectors facing an actual attack have the memory of attack in their minds and cells. We want protectors to say, in effect, "I recognize this, I've seen this before." Otherwise, an attack is apprised as a new thing, and like all new things the mind would want to get involved to assess, evaluate, measure, judge, categorize.