Just 2 Seconds (15 page)

Authors: Gavin de Becker,Thomas A. Taylor,Jeff Marquart

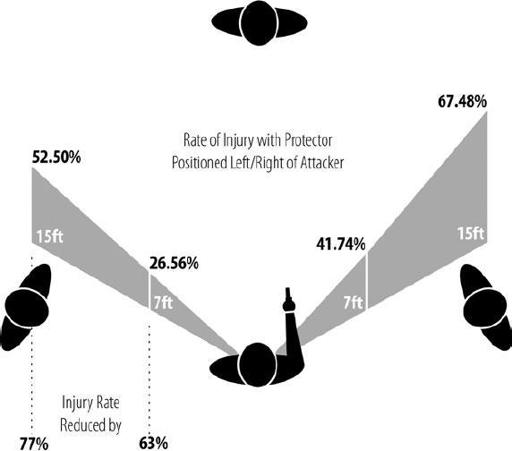

Right vs. Left

TAD research answered some questions most people had never considered. For example, when you assign a protector to a position, does it make any difference whether the protector is posted on the bystanders' right-hand or left-hand side?

We've learned that it is best to position protectors on the

bystanders' left side

because attackers consistently perform more poorly when they are engaged by a protector who responds from their nondominant side -- and for most people, that's their left. Protectors who engage attackers on the attacker's nondominant side are more likely to prevail than those who engage on the attacker's dominant side.

All other factors being equal, merely moving the protector to the left side of bystanders significantly reduces the attacker's likelihood of success -- and thus enhances the safety of the protectee.

Since the protector positioned to the left of the attacker sees the gun an instant later (because the shooter's body is blocking his gun hand during the draw), it might seem that positioning on the left would help the shooter be

more

successful, not less. Also, one might assume that if standing on the left, the protector has to travel farther to reach the attacker's gun arm, thus granting the attacker more time to fire. However reasonable these assumptions, the fact remains that attackers are less likely to prevail when protectors are positioned on the left. Why?

It appears that people are less confident when engaged on their non-dominant side. Attacker nervousness might be enhanced when a protector charges from the left as opposed to the right, as knowing an adversary is on one's weaker side causes more anxiety. And why does the shooter do better when engaged from the right? Again, confidence might be part of the reason. A person engaged on his dominant side is less anxious. Also, since the right is also likely the side of the shooter's dominant eye, a clearer view and better depth perception might serve to discourage flinching when a protector advances from the right. Further, it might be relevant that attackers are more able to maintain footing when assaulted on their dominant side, the dominant side being stronger. Finally, there's the physics of moving the attacker's arm (to destroy accuracy): The right-handed attacker can better resist a push from the right than a push from the left. This is because the attacker has more muscular resistance to force that seeks to move his right arm leftward, than to force that seeks to move his weaker arm rightward.

Studies have shown police officers will resist using their weak hand and attempt to fire handguns with their dominant hand even if their dominant arm or hand has been wounded. All in all, it's clear people feel more confident dealing with challenges that come from their dominant side, and accordingly, we ought not give that advantage to attackers.

Maximize White Space

White Space is the term we use to describe the enforceable open area between protectee and the nearest members of the general public (bystanders, onlookers, audiences, attackers). White Space is ideally maintained as empty of people as possible, so that anyone entering the space (say, climbing over a cordon or barricade) is tipping his intent. The farther away an attacker is when he commits, the better for protectors -- for it means more time to respond. Though cordons and velvet ropes don't physically stop people from entering a space, they do compel anyone who enters the space to send a clear message: "I am violating the rules." Ideally, if there's enough White Space, this message can be received by protectors in plenty of time.

Applying lessons learned from past attacks, we always seek at least 25 feet of White Space. We don't always get it, but when making advance arrangements, we are committed to getting as much as we can. Every foot matters, and every foot is worth negotiating for. When protectees must walk through a gauntlet-type environment (members of the general public or media on both sides, as at a gala event, film premiere, etc.), we try to ensure that the foot-route is as wide as possible. When event coordinators are deciding where the protectee will appear (say, seats or podiums on a stage), we encourage that everything be set up as far back from the edge of the stage as practical. Similarly, we seek to have the front row of the audience as far back as practical.

If there's a barricade, we seek to get as much distance as practical between barricade and stage. Event coordinators and political advisors have many goals (maximize audience experience, encourage the feeling of proximity to the public figure, make the environment look crowded, encourage excitement, foster the illusion of intimacy, etc.). And we have our single goal: Safety.

Photo from Getty Images

White space need not always be obvious to the general public. Above is an example of a public appearance in which the casual observer doesn't perceive any White Space at all -- but it's there. Event designers had the elevated stage platform (in the foreground) crowded with invited supporters, giving the appearance that the protectee is surrounded by an enthusiastic crowd of general public. In fact, he is also surrounded by protectors.

Photo from Getty Images

Though we couldn't get 25 feet of White Space at this event, we were able to maintain an average distance of 10 feet between the protectee and the nearest members of the public by installing and manning a solid barricade around the stage. Closer examination of the photo reveals the four-foot deep corridor occupied by protectors only. Ten of the detail's twenty-four protectors are visible in this photo. Protectors 4, 6, and 7, and one who is blocked in this photo by protector 2, are down on the public level within the corridor. Protectors 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, and 10 are on the stage level, with protectors 8, 9, and 10 maintaining the integrity of the protectee's exit route from the stage. (Attendees at this event also passed through weapons screening.)

White Space is Unnatural

Yigal Amir, the man who killed Israeli Prime Minister Rabin (

Compendium #251

), had been trying to kill him for two years. Because of effective use of White Space on three previous occasions, Amir was unable to get close enough to complete his attack. On the occasion that he was able to get close enough, it was due to the complete absence of White Space. Throughout the Compendium, you'll find cases where successful attackers got as close to their targets as you are to this book.

In Rabin's case, he was shot while leaving a public appearance (as were many protectees shot while leaving events). You've likely observed that things tend to fall apart at the end of events. It is not in the natural order to have things remain in the precise way we'd ideally want them to be throughout a public appearance. The natural order is for things to press in upon things, for people to continue to move forward toward a center of attention, and for order to unravel. Over time at a public event, people are inclined to encroach upon stanchions, ropes, and barricades. Temporary or part-time security personnel hired for an event will, in the natural order of things, lose their commitment to their role as the event winds up (or more accurately,

unwinds).

Accordingly, the wide path of white space that might have been afforded for arrivals is rarely as well maintained hours later when your protectee is departing.

So, since order that was established at the beginning of events often disintegrates by the end, our firm applies an important precept whenever possible: Public Entry, Non-public Departure. If one must enter through the main arrival area because the event requires public entry (for media or other reasons), then it's best to depart by a non-public route. Risk is enhanced as events end, because organizers and local security personnel typically think the job is done, and any semblance of crowd control, attentiveness, and even pride in the event is lost toward the end. Hence, departures are usually less orderly than arrivals. At the same time, an attacker waiting along the exit route has been afforded time to prepare, to see the car being put in place, to judge distances, to observe protective strategies, and to select a position. He might be afforded hours to plan, to prepare himself, to gain confidence. You can, however, take away every single advantage, including access to the protectee, simply by having the protectee depart through an alternate exit. The protectee gets other benefits, such as not waiting for the vehicle, not having to press through a crowd, not having to extend the public appearance, in effect, by continued conversations and encounters with other attendees who are waiting for their cars and making their way through the disorder that characterizes the end of events. A precept worth repeating: Public Entry, Non-public Departure.

Close But Not Too Close

Since we've written so much about the value of being close to the attacker, it may seem contradictory when we add the qualification "Not too close." When members of the general public are crammed up against protectors, just as when protectors are crammed up against protectees, it's not easy to act effectively. Appropriate White Space allows the protectee and protectors to walk freely within the field of space that's maintained. This enhances dignity and looks a lot better than pushing, shoving, and barking things like "Coming through!" But there is more than dignity and appearances at stake: If protectors don't have at least a little space between themselves and those in a position to attack, they can't see anything, and they don't have room to effectively use their arms and hands.