Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation (14 page)

Read Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation Online

Authors: Trevor Wilson

This cycle of political paralysis and insurgency was the backdrop to the country’s economic collapse during the 1980s. In a country with no real external enemies, an estimated 40 per cent of the national budget was being spent on defence; two insurgent blocks, one headed by the NDF and one by the CPB, controlled most borderland areas as well as much of the thriving black market trades in such lucrative items as jade, opium, cattle and luxury goods; and all the time the social and humanitarian costs were mounting. This decline was graphically exemplified when Burma was accorded Least Developed Country status by the UN, in 1987. There are no reliable statistics for casualty figures, and until the mid-1980s the fighting was little reported in the outside world. But there is little reason to doubt the claim of the first SLORC chairman, General Saw Maung, in a landmark admission about the impact of war, made in 1991, that the true death toll since independence “would reach as high as millions”.

14

It is poignant to note, therefore, how few attempts were made to try and end the fighting by dialogue and political means until the post-1989 ceasefires. Individual talks took place between the government and insurgent groups, but they were few and very far between — notably with the KNU in 1949 and 1960; with Rakhine, Pao and Mon groups during U Nu’s “arms for democracy” initiative in 1958; with Muslim Mujahids in 1961; and with the Kachin Independence Organization in 1972 and 1981 (when talks were also held with the CPB). Few talks, however, ended with agreements or lasting ceasefires. Many different counter-insurgency tactics were also attempted by the government over the years, ranging from the political (“people’s war”) to the repressive (the “Four Cuts”).

15

Some of these methods included the recognition of armed opposition groups as

local militia, including the Ka Kwe Ye of the 1960s and 1970s (which over the years switched to and from the government side). But the only face-to-face peace talks of any real size or duration was the unsuccessful Peace Parley held during 1963–64, shortly after Ne Win seized power, while the only nationwide amnesty that included armed opposition supporters was as long ago as 1980.

In the meantime, huge rifts in political vision and understanding developed as fighting raged in different parts of the country. Governmental authority, in the main, was confined to the towns and cities, the central lowlands and coastal plains. In many borderland regions, in contrast, there were often a number of parallel organizations of insurgent or quasistate authority that came to rival a Lebanon or Afghanistan in their complexity.

16

Against this background, disillusion not only with the failures of central government but also with many insurgent groups was building. In 1988 popular protest was instrumental in the collapse of the BSPP government, as demonstrators took to the streets following General Ne Win’s resignation. Within a year the CPB, the country’s oldest political party and most longstanding insurgent group, was also swept away. The CPB’s demise, however, was triggered by a rather different sequence of events in the aftermath of the events of 1988 — by an upsurge of ethnic nationalism in the northeast of the country, as ethnic minority troops from the CPB’s 20,000-strong People’s Army along the China border mutinied and deserted.

In the late 1980s, desperation and the mood for change were clearly widespread across the country. This was highlighted in a statement by the fledgling United Wa State Party (UWSP), broadcast by its radio station in May 1989, shortly before the UWSP agreed on a ceasefire with the new SLORC government:

Every year the burden of the people has become heavier. The streams, creeks and rivers have dried up, while the forests are being depleted. At such a time, what can the people of all nationalities do?

17

It is a measure of how much the socio-political landscape has changed in Myanmar since 1988 that formerly-insurgent groups among such peoples as the Kachin, Shan, Mon, Pao, and Wa took their places as official delegates in the opening sessions of the resumed National Convention in 2004.

Previously such organizations were referred to in the state-controlled media of the Ne Win era only by such terms as “bandits”, “saboteurs”, “racists”, or as leftist or rightist “extremists” to be “eradicated”.

18

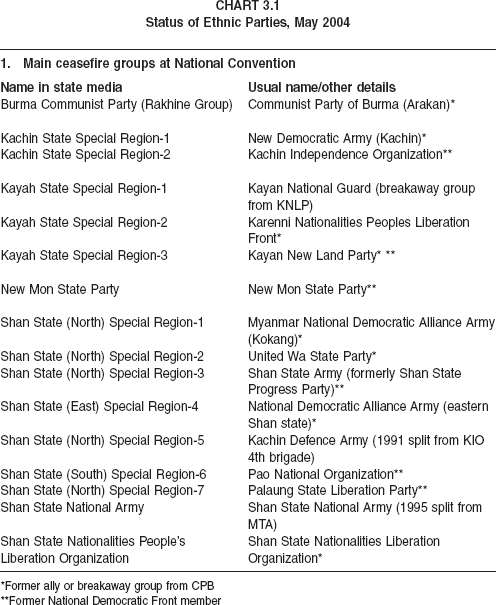

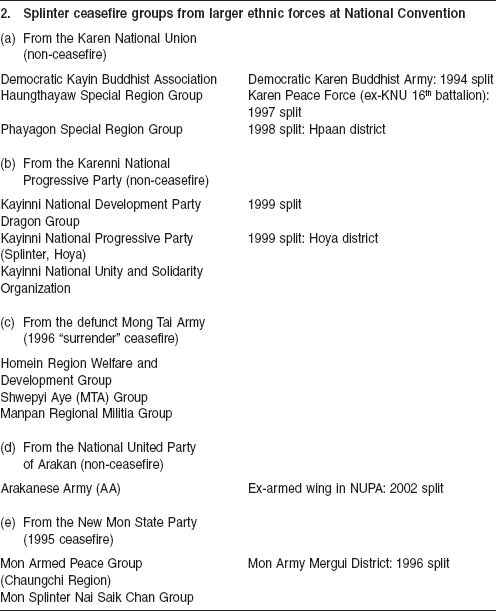

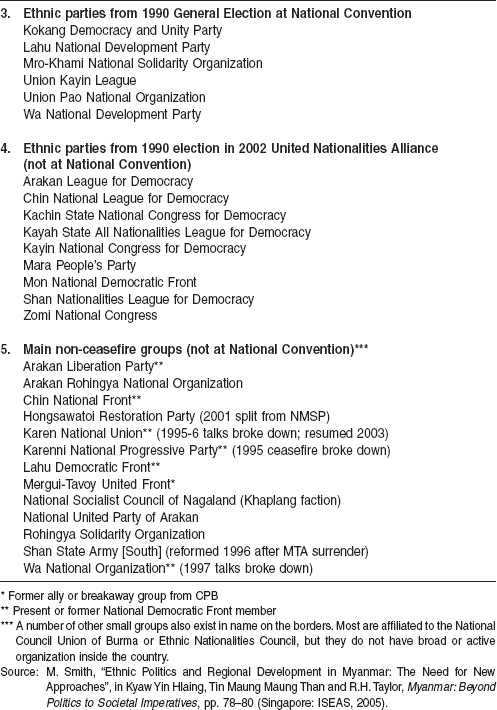

At the same time, it is contemporary reflection of the many dilemmas in Myanmar politics that neither the NLD nor representatives of the nine-party United Nationalities Alliance (UNA), which either won or contested seats in the 1990 general election, were there to join the ceasefire groups at the National Convention (see

Chart 3.1

).

From this paradox, it is apparent that national reconciliation and the SPDC road map have an uncertain way to travel. This concern was publicly reflected by a 17 August 2004 statement from the UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan who, while acknowledging the “potential role” such a body could play in the “transition to democracy” and “national reconciliation”, considered that the National Convention did not “currently adhere” to standards laid down by resolutions of the UN General Assembly.

19

Many questions clearly remain, but for the moment it is important not to lose sight of how much focus was appearing to form in Myanmar politics around the SPDC’s seven-stage road map in the months prior to the National Convention’s resumption. General Khin Nyunt’s announcement of the road map in August 2003 had had immediate and galvanizing effect. In particular, in an otherwise barren landscape, many political strategies and re-appraisals came to be based around it, whether inside or outside the country.

20

Indeed, the possibility of attendance by the NLD and allied ethnic parties at the National Convention appeared to come tantalizingly close in the days immediately prior to the Convention’s commencement on 17 May 2004.

21

Certainly, in terms of ethnic politics the National Convention’s resumption was a moment that many nationality parties had long been awaiting, especially the ceasefire groups, who took it seriously as a potential benchmark of change. Not only had armed opposition groups been unable to stand in the 1990 general election (and few were involved in the earlier National Convention between 1993 and 1996), but they regarded the start of face-to-face dialogue in Yangon in 2004 as a culmination of their ceasefire strategies for reconciliation and reform that had begun over a decade earlier. “We want change now — not in another five years,” said Dr Tu Ja, who headed the Kachin Independence Organization to the National Convention. “That is our thought and basis.”

22

As a result, the National Convention’s revival in reformed shape in the middle of 2004 initially appeared to be another defining moment in the country’s transitional landscape. Indeed, the consequences may yet be profound. In particular, the resumption brought to the surface a difference in outlook and strategy between two groupings in Myanmar politics that had existed since the late 1980s. The groupings are informal and the inter-linkages are in some cases tenuous. On the one hand are the groups that have essentially looked to a “political solutions first” process in bringing about reform. This category includes the NLD, some of the electoral ethnic parties (principally the United Nationalities Alliance members) and the non-ceasefire groups, such as the KNU.

23

Such parties were not represented at the National Convention when it started in May. On the other hand are those groups that believe peace and development initiatives must be pursued as an essential parallel to achieving reconciliation and sociopolitical change that is sustainable. In this grouping have been the military government and ethnic ceasefire groups, as well as many community-based organizations inside the country. Representatives of these organizations and their supporters were at the 2004 National Convention between 17 May and 9 July 2004.

Given the current state of flux, it is impossible at this time to make final judgments about the effectiveness of either strategy in bringing about long-term change. During the past decade both outlooks have had passionate advocates, and both strategies have had some limited impact. In addition, as in any country of “complex emergency”, it is possible to single out particular regions, or particular issues such as HIV/AIDS, narcotics or refugees, in order to determine priorities or present very different pictures of events unfolding in the country. The course of developments in Kachin State and Karen State since 1988, for example, has been strikingly different in many aspects.

However, while it may not be possible to determine which strategies or processes will eventually bring reform, it can be acknowledged in ethnic and insurgent politics during the SLORC-SPDC years. For the moment it can be acknowledged that the social imperatives have, in the main, come to take dominance over the political. In particular, it has become clear that in many long-suffering communities the driving priority has become the desire to achieve peace and progress today — not at some indeterminate date in the future through some unclear process.

The scale of these local factors for change has not always been internationally recognized. Indeed, the spread of the ethnic ceasefire movement was not a historical development that was at all predicted in the aftermath of the 1988 downfall of the BSPP government. Rather, it was armed opposition forces, especially those of the ethnic minority National Democratic Front, that initially seemed boosted when thousands of students and pro-democracy activists took sanctuary in their territories following the SLORC’s assumption of power. Subsequently, a number of members of parliament-elect from the NLD and other political parties followed them, and, in an echo of U Nu’s time with the KNU in the NULF, a new cycle of insurgency appeared to be taking root in the borderlands through such new united fronts as the National Council Union of Burma (NCUB, formed 1992).

24

In subsequent years, it has often been the borderland activities of such groups, many of whose supporters have since gone into exile, that have received the most international media and humanitarian attention, especially in Thailand. Inside Myanmar, however, the momentum of ethnic and armed opposition groups has generally been steered in a very different direction. From a cautious beginning, that direction has increasingly tended towards participation in peace talks, compromise with the government, and efforts to be included in any Yangon-based process of reform.

Among different ethnic nationality parties, a number of reasons have been advanced for such change. A common factor has been the determination among leaders of ethnic forces, who regard their organizations as the vanguard defenders of their peoples, to be on the inside of any political process during any new period of change. In particular, they feel that they have been excluded too many times before in times of transition, and that it has always been the ethnic minorities who have ended up paying the highest price following earlier periods of upheaval in national politics, notably after 1948 and 1962. The late president of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), Maran Brang Seng, explained in July 1990: