Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation (21 page)

Read Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation Online

Authors: Trevor Wilson

Measuring the

fiscal

costs of banking crises is usually substantially easier than estimating lost output, and considerably more accurate. The reason for this is simply because, unlike output costs, the fiscal costs of a banking crisis do not need to be “estimated’; rather, as expenditure of government and/or the appropriate monetary authorities, they could be expected to appear in the accounts of the relevant bodies. This is not the case for Burma, however, since, shrouded in mystery as their actions remain, we still do not really know the extent of financial support given by Burma’s monetary authorities to the distressed banking system. As noted by this author in 2003,

19

much fanfare was made in the middle of the crisis regarding a 25 billion

kyat

loan to three of the worst affected banks, but doubts as to whether this actually took place have not entirely gone away. In the end, IMF statistics reveal that the Central Bank of Myanmar made about 165 billion

kyat

available to banks at the peak of the crisis in the first

quarter of 2003, but some 70 billion of this had been repaid by the first quarter of 2004.

20

Poor banking practices were the proximate cause of Burma’s financial crisis of 2003, but such practices took place in a macroeconomic environment that was hardly conducive to the proper functioning of financial intermediaries. Among banking malpractices most frequently reported, for example, were procedures through which banks lent money to their customers in order to enable them to pursue various inflation-hedging strategies — including investing in the “private finance companies” and speculating in gold and real estate. Such procedures were extraordinarily risky for the banks, since they depended on the “bubble” inherent in each of these strategies, and bubbles are well known for their tendency to burst, as all ultimately did, but they would not have been pursued in the systemically-damaging way they were if it had not been for the fact that chronic inflation would otherwise have impoverished the prudent minded.

Unfortunately, high and persistent inflation is but one of a number of macroeconomic problems that beset Burma. Others include an unstable “dual” exchange-rate regime that rewards rent-seeking behaviour and promotes corruption, a current account position that is usually deeply in deficit, negligible foreign exchange reserves, chronic underemployment, foreign debt arrears, and a policy-making environment that is arbitrary and often irrational.

21

All of these woes, however, have an important root cause — the large and persistent budget deficits that are run up by Burma’s central government. In the latest year for which we have data on Burma’s fiscal position, the 2000–2001 financial year (that is, April 2000 to March 2001), the revenue of the central government accounted for little more than 60 per cent of its spending.

22

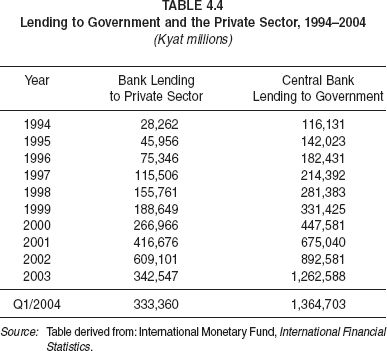

There is little reason to believe this situation has improved (see

Table 4.4

), and what efforts have been made to increase the taxation revenue of the central government have only added to the chaos and confusion that always seem to accompany policy-making and policy implementation in Burma.

One typical illustration of this was the announcement by Burma’s Ministry of Finance and Revenue in June 2004 of a new flat-rate tax of 25 per cent on imports, to replace a differentiated series of duties ranging from 2.5 to 20 per cent.

23

This could be seen as a sensible attempt to bring coherence to Burma’s rates of duty, but the announcement was accompanied by another which declared that the exchange rate used to calculate the value of imports (and upon which the duties were levied) would also rise, from a staggered rate of US$1 = 100–180

kyat

(for different commodities) to US$1 = 450

kyat.

Taken together, these comprised two significant revenue enhancing measures (to the extent they were not evaded), but the effect was rather ruined by the chaos that ensued in Burma’s cross-border trade as a consequence of the abrupt and arbitrary nature of the announcements (after an initial effort to keep the rate rises a secret) and of their implementation.

24

The change in the dutiable exchange rate was itself a sensible development — at US$1 = 450

kyat,

at least it sat in the middle of the divide between Burma’s official fixed exchange rate of around US$1 = 6

kyat,

and the prevailing “market” exchange rate of over 1,000

kyat

to the US dollar. However, the change provided yet another element of uncertainty regarding the value of Burma’s currency, while not removing the obvious incentive for corruption created by the application of differential exchange rates.

In the absence of adequate revenue, the Burmese regime has reverted to the device time-honoured in application but universally ill-starred in its effects — monetization. Simply, the Burmese government borrows from the central bank (effectively “prints money’) to cover its budget shortfall. The monetization of the budget deficit in Burma is shown in

Table 4.4

, as indicated by the Central Bank of Myanmar’s lending to the central government. Not only has this item been consistently growing since a supposedly pro-economic reform regime came to power in Burma, but it also dwarfs the financial resources elsewhere committed by Burma’s financial system (public and private) to the private sector.

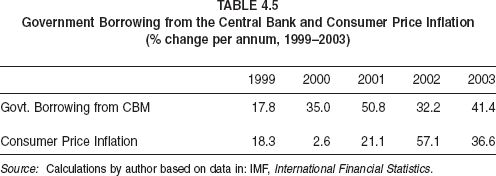

Table 4.5

juxtaposes the government’s “money-printing” with the inflation numbers that are one of its symptoms.

In recent decades, the necessity of establishing clearly-defined and enforceable property rights as a central pillar of an economic development strategy has come to be recognized by economists, development specialists, and policy-makers. Property rights have two critical elements. First, they grant to the individual owner exclusive entitlement to use their property as they see fit (subject to the proviso that this does not infringe on the rights of others), and to enjoy the fruits of this use. Second, they grant to the owner the right to dispose of, sell, or otherwise transfer those rights at will.

25

The first element provides the basis of the incentives to work, to produce, to save, to invest, and to conduct all those other activities that collectively provide the motor of the capitalist economy. The second element is just as important, since it provides the

means

through which capital can be created. Clearly-defined property rights — and their expression in formal legal documentation — have been the basis of collateralized lending for investment in the industrial world for two centuries. Hernando de Soto, the Peruvian economist who has done perhaps more than anyone else to underline the importance of this “second element” of property rights, described its capital-creating mechanism in his seminal book,

The Mystery of Capital,

thus:

In the West ... every parcel of land, every building, every piece of equipment or store of inventories is represented in a property document that is the visible sign of a vast hidden process that connects all these assets to the rest of the economy. Thanks to this representational process, assets can lead an invisible, parallel life alongside their material existence. They can be used as collateral for credit. The single most important source of funds for new businesses in the United States is a mortgage on the entrepreneur’s house. These assets can also provide a link to the owner’s credit history, an accountable address for the collection of debts and taxes, the basis for the creation of reliable and universal public utilities, and a foundation for the creation of securities (such as mortgage-backed bonds) that can then be rediscounted and sold in secondary markets. By this process the West injects life into assets and makes them generate capital.

26

The “representational process” celebrated by de Soto above scarcely functions in Burma. As shall be examined below, it is implicitly undermined by events such as the 2003 banking crisis, during which the relationship between physical property and its abstract representation was severed in significant ways. But the representational process is also

explicitly

undermined in Burma. Various laws, but chiefly the

Land Nationalization Act

of 1945 (as amended 1953), have the effect of prohibiting the pledging of land as collateral.

27

Such laws, of course, negate the ability of entrepreneurs to raise capital in ways commonplace in the United States and elsewhere. Physical property in Burma is left purely in its “material existence” and is assuredly not a device, in conjunction with a properly functioning financial system, for the introduction of “life” into assets, or for self-replication into capital.

28

An inescapable conclusion from Burma’s banking crisis of 2003 is that the country’s relevant authorities were unable, or unwilling, to protect the

property rights of participants in the financial system. Most obviously this was the case with respect to the holders of bank deposits in Burma. This cohort had the rights to their property — their monetary assets — violated in multiple ways, including the complete denial of access to it at critical moments. Such assets ceased even to be useful as the means of exchange, as remittances and transfers ceased, and as established tokens (credit, debit cards and the like) were disavowed.

29

Perhaps even more damaging were the violations of the property rights of borrowers whose loans were recalled by the banks concerned, acting at the explicit direction of the CBM — arbitrarily withdrawing working capital and undermining businesses that had entered into supposedly binding and dependable contracts. Of course, with a number of the private banks, including two of the largest, now seemingly permanently closed, a substantial number of depositors have effectively “lost” their money.

The importance of a credible regime of property rights for banking and financial systems hardly needs to be stressed — financial assets such as deposits are, after all, little more than notations on paper (not even on paper in the case of electronic banking products) that are merely claims on the issuer, an abstract representation of the real assets and resources into which they are meant to be redeemable. They are symbolic, backed up by nothing other than the trust their holders are willing to invest in the corporate entity that issues them. In the developed financial markets of the world this trust has been hard won. As Drake notes: “Those who decide ... to hold financial assets as wealth need the reassurance, which law and custom confer, that it is safe to do so”.

30

Of course, “law and custom” have seldom conferred such safety in Burma, and the 2003 banking crisis is but the latest reminder of this fact.

The most obvious function of money is as a medium of exchange. A more efficient substitute for barter, it is in this role that money allows for the division of labour — famously, one of the factors that Adam Smith posited as partially explaining the “wealth of nations”. But money, especially in its modern form, is much more than simply a means of exchange. As a store of value, money allows for “inter-temporal” decision-making by economic agents. Participants in an economic transaction do not need to instantly

consume the products of their exchange — rather, money allows consumption to be postponed, brought forward and more generally “liberated” from its initiating transaction. In a practical sense, this allows for saving, for investment, and for the longer-term consumption decisions that people make. Finally, money is a unit of account. Often overlooked, it is this virtue that makes possible the calculation of relative prices, debts, wages, and profits — the signals that allow for the “progressive rationalization of social life”.

31