Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation (20 page)

Read Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation Online

Authors: Trevor Wilson

Yet, the difficulty of crafting a more realistic account of Burma’s economic situation should not allow a complacent acceptance of the country’s official statistics by default. Such complacency seems entrenched in certain multilateral agencies, but thankfully a vanguard of scholars and commentators are committed to what must at times seem the Sisyphean task of getting to the truth of Burma’s economy.

3

These scholars have adopted a number of approaches — which Bradford insightfully groups under the labels of “internal” and “external” critiques.

4

The “internal” critiques attempt to match the claimed growth numbers for Burma’s economy with other statistics — such as energy usage, land under cultivation, calorie intake, and so on — that should corroborate the official story of growth if, indeed, it is accurate. “External” critiques, by contrast, examine Burma’s growth performance vis-à-vis what the examples of other countries, and history, tell us is reasonable.

5

Neither internal nor external critiques of Burma’s growth performance, however, are favorable to the claims of its official statistics. Even the Asian Development Bank, an organization not noted for publicly questioning the data of its members, implicitly employed an internal critique to Burma’s official data when it noted that the country’s claimed growth numbers for 2002 were inconsistent with data on the use of certain factors of production — including electricity production (which actually fell), crop acreages, fertilizer and pesticides application, and the consumption of oil and natural gas (all of which were stagnant).

6

More systematically, Dapice critiqued Burma’s growth claims by focusing upon electricity production.

7

He noted that from 1990 to 2000 the generation of electricity in Burma increased by an average of 7 per cent per annum. Employing the well-established rule of thumb that in developing countries such as Burma, electricity generation

invariably grows by 1.5 to three times the growth rate of real GDP, he calculated an implied growth rate for Burma across the decade of something in the order of 2.3 to 4 per cent per annum. The official statistics claimed 6 per cent average annual growth over the same period.

8

The rice sector likewise came under Dapice’s lens, and his finding that the growth of this critical item in the Burmese diet lagged behind the rate of population growth over the 1990s meant that it was likely “that hunger is increasing” in the country, notwithstanding the official figures indicating rapid growth. In its

Country Reports

and

Country Profiles

the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) has long expressed doubt over the official numbers provided by Burma’s relevant authorities. The EIU implicitly employs an internal critique such as those above to provide “alternative” growth numbers for Burma, as in

Table 4.2

.

The EIU’s methodology is not spelt out in its publications, and contains what must necessarily be subjective assessments of whether information is plausible or not. Given the singular lack of plausibility of much of the official data coming out of Burma, “informed speculations” such as the EIU’s are as good as can be reasonably hoped for.

In late 2002, a series of failures amongst certain “private finance companies” (which for the most part were little more than gambling syndicates and “ponzi” schemes) caused a crisis of confidence in Burma’s financial arrangements.

9

Although these firms were not legally authorized deposit-taking institutions, they presented a tempting investment opportunity for Burmese seeking a non-negative return on their funds.

10

Such temptation had an irrational side, in that the promised rates of return were far too high to be credible, but there was a rational side as well, in that the interest rates that Burma’s (authorized) banks can pay on deposits are capped at 9.5 per cent per annum, which is well below the country’s inflation rate (estimated by the IMF at 57.1 per cent in 2002), meaning that putting money in the bank was a (certain) losing proposition in Burma.

11

The crisis in Burma’s private finance companies quickly spread to the country’s nascent (and hitherto fast-growing) private banking sector — a contagion perhaps unremarkable given the country’s history of periodic monetary and financial crises. Long lines of anxious depositors formed outside the banks, a phenomenon that rapidly swelled into an archetypal “bank run”. From this moment on, the response of the relevant monetary authorities in Burma, principally the Central Bank of Myanmar (CBM), was (if unintentionally) almost wholly destructive. Late and inadequate liquidity support to the banks by the CBM was overwhelmingly negated by the imposition of “withdrawal limits” on depositors that escalated into an outright denial to depositors of access to their money. Even worse, loans were “recalled” with little consideration given to capacity to repay. More potent breaches of “trust” in banking would be difficult to imagine. With a full-scale banking crisis now in play, there followed the usual symptoms of such events — bank closures and insolvencies, a flight to “cash’, the creation of a “secondary market” in frozen deposits, the cessation of lending, the stopping of remittances and transfers, and other maladies destructive of monetary institutions. By mid-2003 the private banks had essentially ceased to function. In 2004 selected banks reopened, some of the largest closed completely, and an anaemic recovery began.

12

According to Burma’s official statistics, however, the bank crisis of 2003 did little damage to the country’s economic performance. The estimates of the Central Statistical Office for 2003 and 2004 (see

Table 4.1

) show growth rates in excess of 10 per cent prevailing. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), on the other hand, ascribes negative growth for Burma during these years (

Table 4.2

), principally as a consequence of the banking crisis. It is true, of course, that the number of enterprises affected

directly

by Burma’s banking crisis is relatively low, but their economic importance — as employers, traders, and participants in the most modern and productive sectors of Burma’s economy — is more significant than perhaps their numbers suggest.

The banking crisis allows us another avenue through which to critique Burma’s official story of growth, since (as with energy usage) there exists a parallel set of data related to the experience, from which we can draw. This data set consists of the monetary information the Central Bank of Myanmar provides to the International Monetary Fund, and which the latter publishes each month. This data is subject to many of the problems that confront users of other statistics relating to Burma, but these may, arguably, be less severe. Banks, and central banks, owe their

raison d’être

to the aggregation of numbers, and they have ample incentives for “getting them right”. Financial numbers are also less politically sensitive than those for most other sectors of the economy.

13

They are not widely understood, seldom reported upon in the press (both inside and outside Burma), and there is little in the way of an informed constituency needing to be appeased or deceived.

14

Burma’s financial statistics cannot be regarded as the “truth’, but they might just be a useful tool in helping us move toward this elusive quantity.

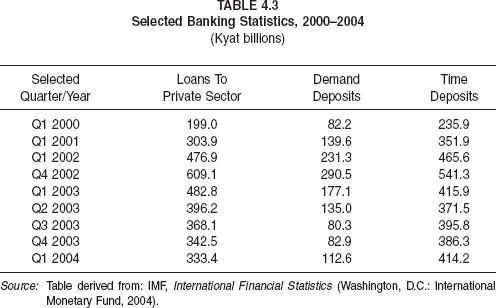

The financial statistics provided to the IMF are unambiguous in pointing to the depth and scope of the damage wrought on Burma’s economy by the 2003 banking crisis. By far the greatest damage, however, was visited upon the private sector — both as borrower and lender. As the first column of

Table 4.3

indicates, bank lending to the private sector in Burma has taken a grievous blow from which it has yet to recover. Private sector lending, the lifeblood of a capitalist economy and a primary source of the working capital of the firms within it, fell a precipitous 45 per cent from its peak immediately before the banking crisis (fourth quarter, 2002) to the latest quarter for which we have reliable information (first quarter, 2004). Certainly some private-sector lending before the crisis was unproductive (especially in underpinning various inflation-hedging schemes) — but it is nevertheless true that it is only upon the adequate provision of capital to the private sector that any hope for Burma’s future prosperity can be entertained. Joseph Schumpeter observed many years ago that the “essential function of credit” was to enable “the entrepreneur to ... force the economic system into new channels”.

15

In Burma today, these channels are decidedly sclerotic.

Such then, was the effect of the Burma’s banking crisis on private sector

liabilities.

But on the assets side of the private sector “balance sheet’, matters are no better. The banking crisis saw “demand” deposits in Burma’s banks also fall precipitously — by 73 per cent from the fourth quarter of 2002 to a low point in November 2003. They have recovered somewhat since but, as at the first quarter of 2004, “demand” deposits remain at only 38 per cent of their 2002 peak. Time and fixed deposits are down 24 per cent from the fourth quarter of 2002, meaning that overall the value of private sector “wealth” in Burma’s banks has been reduced by an astonishing 37 per cent in the wake of the banking crisis.

16

What can we say about the costs of Burma’s 2003 financial crisis to the economy as a whole?

Economists typically estimate the costs of banking crises in two — admittedly rather rough and ready — ways. One way, a “broad” measure, attempts to estimate the

macroeconomic

costs of a crisis by determining any deviation from trend GDP. Among the numerous objections that could be raised against this measure is its implicit

ceteris paribus

(other things being equal) assumption. The second way, narrower but usually more precise,

attempts to measure the fiscal costs of a crisis — the increase in government expenditure that is incurred in bailing out banks, guaranteeing deposits, reforming and restructuring financial institutions, and so on.

17

Measuring the broad macroeconomic costs of Burma’s latest financial crisis is even more problematic than might normally be the case in such situations. Not only are there the universal

post hoc, ergo propter hoc

(after this, therefore because of this) issues noted above but, as has also been noted, we cannot regard Burma’s macroeconomic statistics as being in any way reliable. Great caution is therefore required. Nevertheless, caution duly noted, we can use imperfect but more reasonable alternative estimates, such as those supplied by the EIU, to come up with something that it is at least indicative.

Using ten years of EIU economic growth data for Burma (1993–2002), we calculate a “trend average” real rate of growth of GDP of 6.3 per cent per annum. Accordingly, and once more using the EIU’s estimates for Burma’s GDP growth, but for 2003 and 2004, the macroeconomic costs to Burma of the banking crisis are around 7 per cent of GDP in

each

of these years. Given the higher absolute value of GDP in 2003, it was in this year that the impact was felt more. In absolute terms, we estimate the banking crisis cost Burma in lost output around 560 billion

kyat

in 2003, and 550 billion

kyat

in 2004. Such losses are large by any estimation — indeed, as a proportion of GDP, they are considerably larger than the median output losses experienced in the thirty-three systemic banking crises that have taken place across the world over in the last three decades.

18