Resolute (3 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

Now mystified, Buddington ordered his two mates, John Quayle and Norris Havens, and two of his seamen, George Tyson and a whaler known only as Tallinghast, to walk across the ice pack and board the silent ship. It was not an easy crossing. The four men were forced to struggle over huge mounds of ice and to use ice rafts to carry them over open stretches of water. “As we approached within sight,” Tyson later wrote, “we looked in vain for any signs of life. Could it be that all on board were sick or dead? What could it mean? Surely if there was any living soul on board, a party of four men traveling toward her across the hummocky ice would naturally excite their curiosity. But no one appeared.”

Finally reaching the vessel, they climbed aboard. Spying a name-plate, they discovered that they were now standing on the deck of the HMS

Resolute.

Moving ahead, they encountered the unmanned pilot's wheel. Inscribed in brass letters around it were the words “England expects that every man will do his duty.” This was no whaling vessel. This was a ship of the British navy. But where were her sailors? Nowhere on deck was there a person to be seen. What they found, Tyson later recounted, was “a deathlike silence and a dread repose.”

Spotting the cabin door, they kicked it in, went below, and were astounded by what greeted them. Lamps and vases rested on small tables. Plates, glasses, knives, forks, and spoons were arranged on a much larger table as if the ship's occupants were about to begin a meal. In what was obviously one of the officers' cabins, books lay open, giving the impression that their owners had just stepped out of the room and would return momentarily to resume their reading. The captain's epaulets were draped over a chair. Clothing, toiletries, and scores of other personal items lay neatly about the crew's quarters. Tin playing cards were laid out, indicating that a game had been in progress. A quick check of the galley revealed dozens of shelves of canned meat waiting to be opened. But there was absolutely no member of the

Resolute

aboard. Not a soul. Who were they? Where had they come from? What had happened to them? The men of the

George Henry

had discovered a ghost ship.

Their orders were to report back to Buddington as soon as they had identified themselves to the officers and crew of the mystery ship. Anxious as they were to convey their startling news to the captain, they realized that daylight was rapidly fading. To risk making the return crossing in the dark was to court disaster. They would spend the night where they were.

They awoke to a raging snowstorm, one that kept them aboard the

Resolute

for the next three days. Not that they minded. There were plenty of diversions aboard the spacious vessel to amuse men who had spent the last four months confined aboard their cramped whaleship. “Among other things,” Tyson recorded in his journal, “we found some uniforms of the officers, in which we arranged ourselves, buckling on the swords, and putting on the cocked hats, treating ourselves as

British officers â¦

Well, we had what sailors call a âgood time,' getting up an impromptu sham duel; and before those swords were laid aside one was cut in twain, and the others were hacked and beaten to pieces, taking care, however, not to harm our precious bodies, through we did some hard fighting.”

Not surprisingly, all of the high jinks were accompanied by the drinking of wine that they had found almost as soon as they had entered the living quarters. Later, Tyson would recall the event that followed his first tasting of that wine as the most memorable incident of his initial encounter with the great English ship. “The decanters of wine, with which the late officers had last regaled themselves, were still sitting on the table, some of the wine still remaining in the glasses, and in the rack around the mizen-mast were a number of other glasses and decanters,” Tyson wrote. “Some of my companions appeared to feel somewhat superstitious, and hesitated to drink the wine, but my long and fatiguing walk made it very acceptable to me, and having helped myself to a glass, and they seeing it did not kill me, an expression of intense relief came over their countenances, and they all, with one accord, went for that wine with a will and there and then we all drank a bumper to the late officers and crew of the

Resolute.”

I

T WAS A POIGNANT MOMENT

, hardened whalemen paying tribute to a mysterious crew. Yet before the third quarter of the nineteenth century was over, it would be but one of many similarly remarkable happenings that would take place in a foreboding land which, when the century began, was still mostly a vast blank on the map. This immense, uncharted region would provide the backdrop for one of history's most compelling stories, a saga that would include unforgettable characters, murder, intrigue, cannibalism, unprecedented heroics, triumph and tragedy, and the greatest mystery of the age. It began with the obsession to find the Northwest Passage.

As the second decade of the nineteenth century began, England, having established itself as the ruler of the seas, was about to embark on a new age of discovery, motivated in great measure by the desire to advance scientific discovery. Unknown waters waited to be charted. Unexplored coastlines and the land beyond them needed to be explored and mapped. The inhabitants of these lands needed to be found and their surroundings and ways of life encountered and recorded. Geographical puzzles needed to be solved. What was the source of the Nile? Was the Congo a separate entity or did it join up with the Nile, making them one great river? Could the North Pole be reached?

But there was another, even more deep-rooted, motivation for discovery as well. In a world where trade was paramount to prosperity, failure to discover new routes to coveted markets meant being left behind. And in early nineteenth-century England that meant, above everything else, finding a shorter route to the Orient. Since before Christianity, spices from Asia had been at the core of world trade. But acquiring the pepper, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and other exotic spices meant either dealing with price-gouging Venetian merchants or making the long, expensive, and dangerous voyage around Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope. For more than four hundred years, Europeans had sought a shorter, safer route, one that would allow them to travel directly from the Atlantic to the Pacific by sailing through the Arctic, north of Canada. But did such a passageway exist? That was the big question, one that would make the quest for a Northwest Passage nothing short of akin to the search for the Holy Grail. (The quest for a commercial passage occupied the hearts and minds of men for centuries; see note, page 257.)

None of the earlier searches for the passage had even come close to succeeding. Whatever place names existed on the sketchy Arctic mapâthose of Cabot, Foxe, Hudson, Frobisher, Baffin, and othersâwere names of men who had tried and failed. Throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, as ships disappeared and explorers failed to return, interest in the passage first waned and then all but vanished. By the nineteenth century, however, England had become a much different nation than that from which the pioneer Arctic explorers had sailed. England's Industrial Revolution, combined with a series of ringing military victories, had imbued the country with unprecedented national pride, a confidence that anything, including the discovery of the passage, could be accomplished.

Yet, despite all this, it is safe to say that the renewed effort to find the coveted route would never have taken place when it did had it not been for the determination and efforts of one man. His name was John Barrow and he was unquestionably the father of Arctic exploration.

Barrow's early life gave little indication of how far he would rise or how much influence he would eventually have on future events. He was born in 1764 in the small northern English village of Ulverston where his father was a journeyman farmer. His formal education ended at the age of thirteen when he left school and went to work as a clerk in a Liverpool iron foundry. When he was sixteen, he joined a whaling expedition to Greenland.

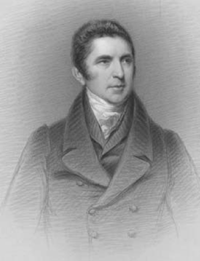

JOHN BARROW

devoted more than forty years of his life to organizing the search for the Northwest Passag.

Humble beginnings indeed but, from the first, Barrow, a dark-haired, moon-faced young man, had demonstrated a high intelligence, a thirst for knowledge, and an appetite for work. Although his education was brief, he had, by the time he left school, proved himself unusually skilled at mathematics and had learned to read and write both Latin and Greek. During his whaling voyage, he had developed a deep interest in navigation and astronomy and had become fascinated with the frigid areas of the far North.

And somehow he had an inborn talent for recognizing opportunity and taking advantage of it. After returning from his whaling venture, he used his mathematical aptitude to get a job teaching the subject in Greenwich. He also earned extra money by tutoring, an activity that unexpectedly changed his life and fortunes. One of the young men he tutored was the son of a wealthy English lord. When, thanks to Barrow's tutoring, his pupil's grades improved dramatically, the lord recommended Barrow to Lord George Macartney, who had just been appointed England's first ambassador to China. On his own, Barrow had learned Chinese, and when Macartney left for his new post he took Barrow with him as his interpreter. Later, when Macartney was given a new post in Africa, Barrow accompanied him as his aide.

Serving with Macartney in Africa soon provided Barrow with yet another opportunity to further what was rapidly becoming a meteoric career. While there, he met and impressed General Francis Dundas, a member of one of England's most powerful and influential families. Dundas's uncle was Lord Henry Melville. And, when Melville was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty, both Macartney and Dundas convinced him to name Barrow the Admiralty's Second Secretary.

It was unprecedented in British class-dominated politics. This son of an itinerant village farmer had, before he was forty, risen to one of the most prestigious positions in the nation, an office which, in fact, was far more powerful than the name implied. Under the English naval system, the Admiralty was overseen by a board made up of seven lords and two secretaries. None of the lords had any true knowledge of or interest in naval affairs. It was the secretaries who made the decisions, which they then recommended to the board. Like the members of the board, the First Secretary was a member of Parliament whose main responsibility was to deal with all political matters that concerned the navy. It was the Second Secretary who was responsible for day-to-day operations and, if he was so inclined, was in the position to initiate key policy decisions. And John Barrow was more than willing, able, and ambitious enough to take on this responsibility.

Barrow officially became Second Secretary in 1804. Except for a one-year period, he would serve in that post for more than forty years. He brought to the position not only his intelligence and his skills, but also his extraordinary devotion to work (some historians have estimated that he read and answered some forty thousand letters a year) and his unflagging dedication to any cause about which he was passionate. During his first thirty-five years in office, the British navy waged five wars in which, among other victories, the last remains of French naval power were eliminated, the Algerian pirates were finally overcome, the Chinese fleet was destroyed during the Opium Wars, and the Egyptians were driven out of Syria. But, despite these triumphs, military victory was not his main interest. His consuming passion was exploration, particularly that which would lead to the discovery of the Northwest Passage.

Most of this passion was motivated by pure national pride. He was convinced that the search for the passage (and for the exploration of other areas of the world) would immeasurably enhance England's contribution to scientific knowledge. “To what purpose could a portion of our naval force be,â¦more honorably or more usefully employed,” he would write, “than in completing those details of geographical and hydrographical science of which the grand outlines have been boldly and broadly sketched by Cook, Vancouver, and Flinders, and others of our countrymen?”

Barrow was, of course, also motivated by the commercial advantages that a Northwest Passage would bring. But perhaps more compelling than anything elseâeven greater than his obsession with exploring the unknownâwas his almost obsessive desire to make certain that no other country such as the United States or Russia be the first to find the passage. For him nothing less than national honor was at stake. “It would be somewhat mortifying,” he stated, “if a naval power but of yesterday should complete a discovery in the nineteenth century, which was so happily commenced by Englishmen in the sixteenth.”

Fortunately for Barrow the time had never been so propitious to launch his passage quest. English ships were more powerful than ever, the fruits of the Industrial Revolution were making more money available to the Admiralty than ever before, and there were, he believed, officers in the British navy bold and skilled enough to make it happen. “From the zeal and abilities of the persons [to be] employed in the arduous enterprise,” he predicted, “everything may be expected to be done within the scope of possibility.”