Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (51 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Guests were always welcome—with or without children. Naomi Decter, Midge Decter’s daughter, remembers Stanley telling her and her sister in mock seriousness, “Whatever you do, don’t jump on the bed”—if they did, a magical creature who lived in the woods behind the house would come and take them away to his fantasy land. Naturally, as soon as Stanley closed the door, they began jumping on the bed as hard as they could. A rotating series of friends settled in the back apartment for short- or long-term stays. “It was full of life, full of kids, full of bustle,” says Midge Decter. It was also full of animals—at least three dogs over the years and countless cats. Some guests would complain about the mess and the cat smell, but others did not seem to notice. Decter remembers the house as homey and untidy, but not dirty. “It was writing clutter . . . not filth, not at all.”

“The doors were always open,” remembers Marilyn Seide, Walter Bernstein’s sister and a Bennington alumna. In the late years,

when Shirley was suffering from agoraphobia, students were no longer as welcome, and Bennington alumni from the early and mid-1960s remember her as taciturn and withdrawn. But throughout the fifties, the Hymans were famous for their parties. Shirley served exotic delicacies she brought back from New York: pickled cantaloupe and cinnamon jelly from Altman’s, stuffed grape leaves and feta from Sahadi’s. She loved to seek out the latest in gourmet foods, the more extravagant the better: one year for Father’s Day she and the children presented Stanley with a four-foot-long smoked cheese. And there was a bottomless well of alcohol. “Everything was somehow provided for everybody,” remembers Catherine Morrison, a student at Bennington in the midfifties. (After Morrison told Shirley that she had never witnessed a birth, Shirley once came to her dorm room to fetch her when one of the cats was having a litter of kittens.) Shirley had a way of taking care of the social niceties without appearing to pay much attention to them. One year Midge Decter and her husband, Norman Podhoretz, visited while Shirley and Stanley were celebrating their anniversary. “There was this great spread—where it came from, how it had been produced, or when, you wouldn’t know,” Decter says. “She did everything as though it was not the least bit of trouble.”

Students and faculty would gather in the front rooms, forming one circle around Shirley and another around Stanley as each held forth, “rarely letting anybody else interrupt.” As the years went on and she put on more weight, Shirley “took up literally half the sofa,” her friend Harriet Fels, wife of Bennington president William Fels, recalled. “But when she opened her mouth, everything changed. . . . She was witty, brilliant, and she knew it and used it.” The atmosphere was homey and welcoming. “Stanley and Shirley were particularly protective of the [Bennington] girls,” Morrison says. “They were a surrogate family.” At one gathering, Suzanne Stern entertained a group of faculty members by doing imitations. She was delivering a lecture on

Moby-Dick

in the style of Howard Nemerov when Nemerov walked in. The group was delighted. “Don’t stop!” everyone yelled. Stanley once deftly defused an argument that had broken out between Podhoretz and another guest.

During another party, late in the evening, Shirley startled Claude

Fredericks by showing him a human skull, which she said had belonged to a doctor. The top of the cranium had been sawed off and reattached with hinges; Shirley opened and closed it as if it were a cigarette box. She tried to hang her commedia dell’arte mask on the skull, but the mask wouldn’t stay put. “She began to speak to it as if it were a child, as if the skull were the ghost,” Fredericks later remembered. “ ‘What, you don’t want it on, it hurts your eyes, you’re tired of it on?’ she asked the creature. . . . There was something unpleasant and ghostly there in the dark, something obscene as she gently, tenderly, almost reverently put the skull back in its place on the shelf.” He was relieved when the arrival of other guests “cleared the air.”

Even during her most social years, Shirley would sometimes withdraw from parties to write, just as Kit Foster remembered her doing in the house on Prospect Street. “We’d all be sitting at dinner and Shirley would excuse herself . . . and retire to her room. Whenever she needed to write, she wrote,” Morrison says. “Hours later she would come out with a draft of something and rejoin if anybody was still there.” Morrison understood Shirley’s behavior as almost involuntary. “The ideas were churning, churning all the time. I had the sense she felt that if she didn’t write them, she was going to lose them.” Another guest remembered her “sitting on the edge of the group” at house parties, “absorbing lemur-like every shade and texture of the person she was talking to. I always had the feeling that she knew just what it was like to be another person, that she grasped and understood to an almost frightening degree.”

As the sale on the house was finalized, Shirley, riding high on her new best-seller status, was jubilant about the future. After years of living from one check to the next, she and Stanley now had a house, a car, and money in the bank, thanks to

Savages

. “it may be bad luck to say it, but right now there doesn’t seem to be anything more we need in the world . . . we are about as lucky as we can be,” she wrote to her parents. “keep your fingers crossed, and knock on wood; there doesn’t seem to be anything that can go wrong.”

12.

THE BIRD’S NEST

,

1953–1954

Everything was going to be very very good, so long as she remembered carefully about putting on both shoes every time, and not running into the street, and never telling them, of course, about where she was going: she recalled the ability to whistle, and thought: I must never be afraid.

—

The Bird’s Nest

“

T

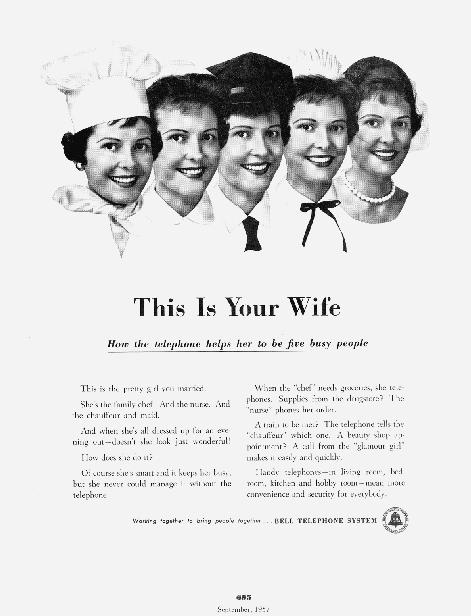

HIS IS YOUR WIFE,

”

THE CAPTION OF THE BELL TELEPHONE

ad reads. Above it, five identical women’s heads are lined up in a row. One head wears a chef’s toque; the next, a nurse’s bonnet; another, a chauffeur’s cap; and so on. Thanks to the telephone, readers are told, “the pretty girl you married” can order groceries, call for a sick child’s medicine, find out what time to meet her husband’s train, and more. Behold the modern American housewife: five women neatly bundled into one.

The ad makes literal an argument common in the women’s magazines of the late 1940s and 1950s: that a housewife need not consider herself “just a housewife.” Rather, she is a specialist in multiple fields at once: “business manager, cook, nurse, chauffeur, dressmaker, interior

decorator, accountant, caterer, teacher, [and] private secretary,” as one article put it. The fact that many housewives apparently needed to be reassured of their own significance demonstrates that they found the media’s glorification of their role far from convincing. But those who hoped for more might have been scared off by the many cautionary magazine stories of the era about women who struggled—and failed—to integrate career and home. One feature described a woman who had tried to pursue a promising career as a concert performer until “the tension of trying to fulfill multiple roles” caused her to have a nervous breakdown. How much safer it was to domesticate those multiple identities into a single category—and better for the family, too. “Few men ever amount to much when their wives work,” the woman concluded. The success of Herman Wouk’s best-selling novel

Marjorie Morningstar

, about a woman who dreams of becoming an actress but is sidelined by an unhappy love relationship, demonstrates how powerfully the theme resonated.

Just as pressure mounted for women to give up careers and embrace domestic life, there was a sudden uptick of popular interest in multiple-personality disorder, a psychiatric diagnosis that had fallen out of fashion fifty years earlier. “Split personality seems to be the literary vogue this season,” one of the reviewers of

The Bird’s Nest

, Jackson’s third novel, commented in 1954, pointing to two other books with a similar theme. (One,

The Three Faces of Eve

, would be made into a popular movie.) Postwar Americans generally showed an increased awareness of mental health issues—a result of veterans returning traumatized from the war as well as of the growing popularity of individual psychotherapy and pop psychology. In Hollywood, psychoanalysis was openly discussed: Marilyn Monroe saw five different analysts, including Anna Freud, starting in 1955. But the particular focus on multiple-personality disorder may well have had more to do with the cultural anxiety surrounding the reorientation of women’s lives around the domestic sphere. The idea that a woman’s identity might comfortably encompass more than one persona—wife, mother, and professional, for instance—threatened a male-dominated culture invested in glorifying the stability of family

life based on traditional gender relations and keeping women out of the workforce. This anxiety is at the heart of

The Bird’s Nest

, in which a dramatic battle of wills takes place between a male doctor struggling to cure a patient on his terms and her multiple personalities, which will not be easily subdued.

When Elizabeth Richmond, a clerical worker at the town museum, arrives at her desk one Monday morning, she discovers that the wall of her office has been removed. As she sits at her typewriter, she can extend her arm into a gaping hole that reveals the building’s “innermost skeleton.” The museum, it seems, has begun to list dangerously, its foundations sagging; the efforts to repair it have only made things worse. The relationship between the building’s disrepair and Elizabeth’s own mental state is strongly implied. “It is not proven that Elizabeth’s personal equilibrium was set off balance by the slant of the office floor,

nor could it be proven that it was Elizabeth who pushed the building off its foundations,” the novel tells us, “but it is undeniable that they began to slip at about the same time.”

Elizabeth is a shy woman, only twenty-three years old, whose personality is so “blank and unrecognizing” that her coworkers barely register her presence. She has “no friends, no parents, no associates, and no plans beyond that of enduring the necessary interval before her departure with as little pain as possible.” Since her mother’s death, four years earlier, she has lived with her loud, abrasive Aunt Morgen, who harbors an unexplained grudge against her late sister. Lately the placid surface of their life together has been marred by disruptions. Elizabeth has begun to receive threatening letters addressed to her at work: “ha ha ha i know all about you dirty dirty lizzie.” Aunt Morgen accuses her of sneaking off to meet a man in the middle of the night, but she has no memory of leaving the house. Visiting friends one evening, she repeatedly insults them—also without being aware of it. And her head aches nearly all the time.

“I’m frightened,” Elizabeth tells Victor Wright, her psychiatrist, at their first meeting. Pompous but well-meaning, given to quoting Thackeray (“A man’s vanity is stronger than any other passion in him”) and fulminating against modern trends in psychoanalysis, he believes at first that she has a mental blockage similar to a clog in a water main; if he can find the source of the trauma and clear it away, she will be cured. When he puts her under hypnosis, a standard treatment in the 1950s, something unexpected happens. Elizabeth’s stuttering speech and confusion disappear and a second persona emerges, calm, helpful, and agreeable; Dr. Wright even finds her attractive. But as he gazes upon her features, they are replaced by “the dreadful grinning face of a fiend.” Here is a third, Gorgon-like Elizabeth: “the smile upon her soft lips coarsened, and became sensual and gross, her eyelids fluttered in an attempt to open, her hands twisted together violently, and she laughed, evilly and roughly, throwing her head back and shouting.” This personality calls him “Dr. Wrong,” threatens him (“Someday I am going to get my eyes open all the time and then I will eat you and Lizzie both”), and is locked in a continual struggle for dominance over the other two.

Demonic possession is the first thought to cross the doctor’s mind: “Hence, Asmodeus,” he mentally commands after the third personality appears. But, acknowledging that “one who has raised demons . . . must deal with them,” he remembers his psychology, quoting Morton Prince, author of

The Dissociation of a Personality

(the psychology text Jackson consulted while researching the novel), on the “disintegrated” personality. According to Prince, in a case of multiple personality, each “secondary” personality constitutes part of the “normal whole self.” Prince theorizes that such fragmentation occurs as a result of trauma: Dr. Wright speculates that in Elizabeth’s case it was the death of her mother, in which she is implicated in a way that is not yet clear. He initially hopes to vanquish the demon, freeing the second personality to exercise her charms—perhaps in his company. But he soon realizes that his real task is to reassemble the personalities as one, as the nursery rhyme that gives the book its title prefigures: “Elizabeth, Beth, Betsy and Bess / All went together to find a bird’s nest.” After a fourth personality emerges, Dr. Wright comes to think of them by those names. Elizabeth is the original dull character; Beth, utterly charming, with whom he falls a little bit in love; Betsy, her evil twin, childish, vulgar, and cruel; and Bess, vain and materialistic. He sees himself “much like a Frankenstein with all the materials for a monster ready at hand, and when I slept, it was with dreams of myself patching and tacking together, trying most hideously to chip away the evil from Betsy and leave what little was good, while all the other three stood by mockingly, waiting their turns.” But how will he put them back together? And what will be the result?