Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (48 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

“I don’t believe it when Sally tells about giants. Do you?”

“Certainly not,” I said. “She’s just making it up.” And recognized clearly that there was no ring of conviction whatever in my voice. “My goodness,” I said heartily, “who’s afraid of

giants

?”

Stanley is noticeably absent from these stories. When he appears, it is usually only to demonstrate his incompetence in any and all practical matters, though he does get some of the book’s best lines: when Laurence asks, “Who was Aristides the Just?” Stanley replies distractedly, “Friend of your mother’s.” His blunders are harmless. At one point, his attempt to kill a bat is foiled by a cat, who runs off with the intruder in her mouth, nodding “contemptuously” at Stanley. Later, he orders a package containing 150 coins from around the world and 100 counterfeit coins; they arrive jumbled together, forcing him to spend hours sorting out the real from the fake. (Shirley had come up with the idea of Laurence starting a coin collection as a way of keeping him busy while he was recuperating from his accident—“if anything were to be collected, for heaven’s sake it might as well be

money

”—but Stanley, always the collector, joined in with equal enthusiasm, and would continue to accumulate rare coins long after Laurence lost interest.) In

Raising Demons

, he would be treated less tolerantly. But for now, Jackson chose to depict him as hapless, clueless, and largely peripheral to the workings of the household.

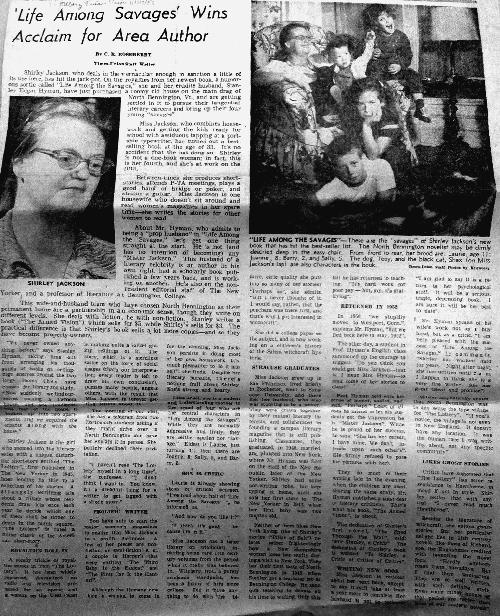

If Stanley was annoyed by this, he displayed it only briefly, when a reporter from the

Albany Times-Union

came to profile Jackson after

Savages

was published. “She has her career, I have mine. We don’t intrude upon each other’s,” he insisted. He also “firmly refused” to pose for any pictures with her. Instead, the photograph with the article depicted Jackson in an overstuffed armchair, all four children tumbling around her, a black cat in her lap, and the dog, Toby, at her feet. Unusually for a publicity photograph, she is smiling broadly. She and the children are the stars of this show.

IRONICALLY, THIS UTTERLY

innocent portrayal of the Hymans as an all-American family—one reviewer of its sequel wrote that the books would be “good red, white and blue publicity” if translated into Russian—was written while they were under investigation by the FBI for alleged Communist activity. Suspicions were first raised when Shirley and Stanley arrived in Westport. As movers were

unloading the truckload of books, one of the cartons broke open. Inside were numerous books and pamphlets by Stalin, Earl Browder, Howard Fast (then the editor of

The New Masses

), and others. One of the movers informed the FBI, kicking off an investigation that would continue for the next two years.

Jackson, all four children, and Toby photographed for the

Albany Times-Union

in 1953, just after

Life Among the Savages

was published

.

Fortunately, the agents in charge of the case did not discover that Stanley had actually been involved with the Communist Party during his years at Syracuse University. But they did determine quickly from his phone records that among his associates were several known Communists. Walter Bernstein had already been blacklisted and was working

under a pseudonym, when he could. Jay Williams, too, had been a literature director of the Party as recently as 1947 and was still on Party mailing lists. The agents identified Shirley as a writer but declined to make her a target of the investigation.

Their focus was on Stanley. Agents interviewed the Hymans’ landlord as well their neighbors in Westport and several people affiliated with Bennington College. The landlord confirmed that the Hymans had “a tremendous number of books in their home,” with “bookcases all around the house”—so many that the agents wondered whether Stanley might be “a custodian of Communist Party property.” Stanley, the landlord testified, was “not friendly” and did not “mix in any activities” in the Westport area. The Hymans did receive frequent visitors from New York, but as far as he knew, there was nothing to indicate that they were “un-American or connected with subversive activities.” The other people interviewed were either unaware of who Stanley was or echoed the landlord’s judgment. A neighbor said that Stanley and Shirley largely kept to themselves, but the lights were on in their home “practically every night” and various cars could be seen coming and going. An administrator at Bennington said that “although she did not like either [Stanley] or his wife personally, she never observed any indication of disloyal activities or disloyal associations” on their part. A Bennington faculty member, too, said that he “intensely disliked” Stanley but had no reason to question his loyalty to the United States.

If Stanley was aware that he was under investigation, he does not seem ever to have mentioned it to anyone. Shirley’s writings contain only one veiled hint. In a draft of

Savages

, she identified the family’s decision, in spring 1952, to move back to Vermont as motivated by “a growing tension, a sort of irritable pressure which none of us could define.” The finished version of the book omits this line. Did she remove it out of caution that it might be read as a reference, however oblique, to the investigation? Or did the author of “The Lottery,” exquisitely sensitive to disturbances in the local atmosphere, simply pick up on the climate of suspicion that the FBI investigation must have created? Either way, after a year and a half of life in Westport, she and Stanley were already contemplating a return to North Bennington.

REGARDLESS OF WHETHER

Jackson was aware of the FBI investigation, one event in particular catalyzed her desire to leave Westport. In June 1951, the relative anonymity that she had been enjoying came abruptly to an end. The family had chosen to leave North Bennington for a variety of reasons, including the village’s distance from New York and Hyman’s loss of his teaching job, but foremost among them was the response of their neighbors to “The Lottery”: in the village, Jackson would be forever recognized as the author of that story. For a year and a half in Westport, nearly everyone knew her only as Mrs. Stanley Hyman—until a publicist from

Ladies’ Home Journal

, which was running one of her stories for the first time, drove up to Connecticut in search of her. Just as he stopped in the drugstore to inquire about the elusive Shirley Jackson, Laurence happened in to buy some chewing gum and volunteered that the mysterious writer was his mother. The local paper promptly trumpeted the news: the author of “the famed short story ‘The Lottery’ ” was living in the neighborhood! Jackson was plainly nonplussed. “I wish this was timed better,” she complained to the reporter. “I am not exactly interested in the public eye right now.”

Jackson was never interested in the public eye. In addition to her hatred of publicity photos, she would eventually refuse to engage in any promotional activities for her books at all. But at that moment in her life, she was especially hostile to scrutiny. The “irritable pressure” she was suffering from began with the string of bad luck in 1950—Emma’s crack-up, the Fresh Air Fund fiasco, Laurence’s bike accident and the ensuing complications—and continued through the following year, spreading like an ugly stench from the household into her professional life. The critical reaction to

Hangsaman

was lukewarm. Several stories she wrote remained unsold, including “The Missing Girl,” inspired by the Paula Welden case, and “The Lie,” about a woman who returns to her hometown to expunge a guilty secret from her conscience. Jackson began but did not finish a new novel, alternately called

Abigail

or

Another Country

, about a pastoral dream world not unlike the commedia

dell’arte: “it was a novel i liked but no one else did so i put it away,” she commented later. And she wasted several months working on a treatment for a movie about the dancer Isadora Duncan. The actor-turned-producer Franchot Tone, best known for his starring role in

Mutiny on the Bounty

(1935), had sent Jackson a telegram out of the blue in the spring of 1951 asking her to collaborate on the project. She was initially thrilled, especially after the director Robert Siodmak, “a flowery character,” offered to fly the whole family to Capri while she wrote the movie. But in the end nothing came of it except months of protracted and frustrating negotiations.

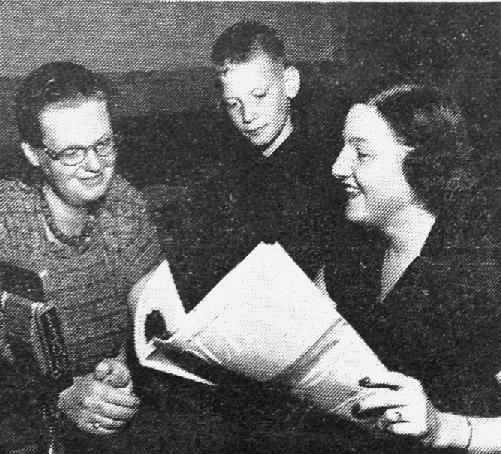

Jackson with Laurence and reporter Jane Connors of WLIZ (Bridgeport, Connecticut), 1951.

Meanwhile, Herbert Mayes, her editor at

Good Housekeeping

, was pressing Jackson to fulfill her obligation to the magazine, which was still advancing her $1500 quarterly with the expectation that she submit at least eight publishable pieces a year. But he rejected almost everything she sent him as “too depressing” (“Still Life with Teapot and Students”), too long (“Fresh Air Diary”), or otherwise unsuitable. The magazine published a couple of the pieces that would make their way into

Savages

, but strangely, Mayes wasn’t as interested in Jackson’s nonfiction. Instead, his taste ran to exactly the sort of stories she least liked to write: wholesome fables about lovers overcoming minor obstacles or children misbehaving adorably. In a tart letter, he suggested she reread her own story “The Wishing Dime” for “a quite definite idea of the short fiction we like.” Until she managed to hit the mark, not only would

there be no more money from

Good Housekeeping

: in March 1951 Mayes demanded that she repay $4000.

This disastrous outcome of a contract that had seemed so promising brought an end to Jackson’s relationship with the MCA agency, which she blamed for the debacle. She had her eye on Bernice Baumgarten of Brandt & Brandt, known as “the toughest agent in the business.” In November, Jackson sent her a brief, no-nonsense letter requesting representation. Within a month, Baumgarten was shopping her stories. The wife of author James Gould Cozzens, whose novel

Castaway

had fascinated Jackson and Hyman in college, Baumgarten had smooth, elegant dark hair and blue eyes. The author and film critic Stanley Kauffmann, another of her clients, remembered her as “small, quiet, and neat.” But her manner was deceptive: Baumgarten was an aggressive negotiator. Jackson would later say that “there is nothing she likes better than getting someone . . . by the throat.”

Baumgarten had started at Brandt & Brandt as a secretary in 1924; she became the head of the book division two years later, at the age of twenty-three. By the time she retired, in 1957, her client list included Thomas Mann, E. E. Cummings, Edna St. Vincent Millay, John Dos Passos, Ford Madox Ford, Mary McCarthy, and Raymond Chandler. Like Jackson, she used her maiden name professionally, though Carl Brandt senior, the agency’s founder, suggested that she change it because Baumgarten sounded too Jewish. (Cozzens, notorious for his anti-Semitism, once remarked that part of the reason he and Baumgarten chose not to have children was that he didn’t want a son of his to be kept out of Harvard’s exclusive—and restricted—Porcellian Club.) Also like Jackson, Baumgarten was the primary breadwinner for much of her marriage, supporting her husband through a dozen less-than-lucrative novels. And she was a blunt talker with a wry sense of humor that Jackson appreciated. “Personally I think all children are born immoral,” Baumgarten wrote after Mayes rejected a story because he didn’t approve of the way a child’s behavior was depicted. She told her client Jerome Weidman, after reading a scene in his novel

The Third Angel

(1953) in which the hero rapes a prospective girlfriend on their first date, that bringing a dozen long-stemmed roses would

be more appropriate. Weidman said the man couldn’t afford roses. “He can certainly afford a philodendron plant,” Baumgarten replied. When Hortense Calisher, whose short stories had begun appearing in

The New Yorker

shortly after Jackson’s, asked Baumgarten whether she should take a job teaching writing at a correspondence school, Baumgarten told her, “When we come to sell your soul, we’ll get a damn fine price for it.”