Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (43 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

As Ellison’s work on

Invisible Man

progressed, he continued to lean on both Hyman and Jackson for guidance. On a visit to Vermont a few years earlier, he and Hyman had jointly written an outline of the novel, then called

The Invisible Man

. That outline helped Ellison, under contract with the small firm Reynal and Hitchcock, get a more lucrative deal with Random House. In April 1951, Ellison wrote to his friend Albert Murray, a younger student at Tuskegee who would become a well-known literary and music critic, that he had “finished most of [

Invisible Man

] at Hyman’s place in Westport.” That time it was Jackson, who was

looking over her page proofs for

Hangsaman

, who proved most helpful. “I had been worrying my ass off over transitions; really giving them more importance than was necessary, working out complicated schemes for giving them extension and so on,” Ellison wrote. “Then I read [Shirley’s] page proofs and saw how simply she was managing

her

transitions and how they really didn’t bother me despite their ‘and-so-and-then-and-therefore’—and then, man, I was on.”

Professionally, it was useful for Jackson as well as Hyman to be closer to New York. She joined the Pen and Brush, a Greenwich Village club for women in the arts, where she enjoyed meeting her agent for cocktails and hoped, one day, to bring her mother, no doubt out of the desire to demonstrate her success. She was especially pleased that Hyman, who didn’t “belong to anything yet except the folklore society, which doesn’t have a bar,” wasn’t allowed in unless she accompanied him. (He, as usual, was working on everything other than the book he was supposed to be writing: book reviews, conference papers, and, at last, two longer pieces for

The New Yorker

: the profile of Scher and a history of the Brooklyn Bridge.) Jackson was mentioned often in articles about promising young authors, including a piece by Cowley in

The New Republic

in which he included her in a group of emerging writers along with Bellow, Stafford, Capote, and Eudora Welty. Invited to a dinner where everyone was “a rich writer and had written a best-seller,” she was pleased and surprised to discover that all the guests had heard about her sensational short story collection. Still, she and Hyman found the other guests “very dull and too shrimp newburg-y for us . . . no chips on the china, napkins for everybody, eighteen matched cocktail glasses, and so on. . . . there’s money in writing, if you work it right.” (“Don’t you like matched china and napkins for everybody?” Geraldine wrote back cluelessly.)

Jackson’s letters to her parents from this period are filled with references to how challenging it was to make a living as a writer—“if i don’t get these three stories out today we will never be able to pay the grocery bill”—as well as a subtle pride that she was able to pull it off. Eleanor Kennedy, her third agent at MCA, had retired in 1949, so she had been passed on to yet another agent, Rae Everitt, the head of

MCA’s literary department.

Lottery

’s success meant that Everitt could ask Farrar, Straus for a larger advance for Jackson’s next novel. At a cocktail party where a tipsy Jackson encountered Roger Straus, she called him “the biggest crook in town” and announced that she wanted $25,000 for the new book. Fortunately for her, he laughed off both the insult and the demand. “as long as he is amused when i call him a crook in front of half a dozen of his other authors i can’t leave [the firm],” she wrote to her parents. More realistically, Everitt hoped for $5,000: “we’ll take four, we figure, and can be talked into three, but it will take a lot of talking.” In fact, $3,000 was the advance they settled on in June 1950, when Jackson submitted the first third of the novel that would become

Hangsaman

, now titled

Natalie

. (Another early title was

Rites of Passage

.) Everitt found it “intriguing” and “wonderful as hell,” and Straus congratulated Jackson on “a brilliant job.” The book was scheduled for April 1951.

Since money was coming in from multiple sources, the amount of the advance was not as crucial to Jackson as it had once been. “The Lottery” had been made into a television play, bringing in nearly $1000, and June Mirken was now fiction editor at

Charm

and buying all the stories by Jackson she could. One of these was “The Summer People,” the eerie tale Jackson had written in the wake of “The Lottery” about what happens to an elderly couple who unexpectedly decide to stay another month in the house they rent every summer.

The New Yorker

had passed on the story two years earlier, with Lobrano arguing that it was a “subsidiary theme” to “The Lottery” and felt “anti-climactic” in comparison. After “The Summer People” ran in

Charm

in 1950, it was selected for

Best American Short Stories 1951

. By the summer of 1950, in addition to her retainer from

Good Housekeeping

, Jackson had sold two more stories to women’s magazines. “With six thousand bucks in a lump, we are finally ahead, and hope to stay that way for a while,” Hyman wrote triumphantly to Zimmerman.

The money, as always, would go quickly. In addition to the playhouse and all the other outdoor amusements for the children, Jackson bought a spinet, which she had been longing for, and a washing machine, her first. Hyman bought her a fur coat; he also loaned $1000 to his father,

joking that the surprise “should take ten years off his life.” A bigger luxury, if more practical, was a live-in maid named Emma, whom Jackson called, with only slight hyperbole, “the greatest blessing” ever to happen to the family. (“You’d better work hard at your writing to be able to keep her,” Geraldine warned.) Emma made the children’s breakfast, allowing Jackson to sleep in and wake up to a pot of hot coffee; she also prepared lunch and dinner, so that Jackson could write uninterrupted in the afternoon. Best of all, with Emma to look after the children, Jackson was free to go into the city as she pleased. Life at Castle Jackson was looking up indeed. Yet 1950 would soon bring a series of unhappy events, some minor and others much more significant, that combined to shatter Jackson’s equilibrium and erode her confidence.

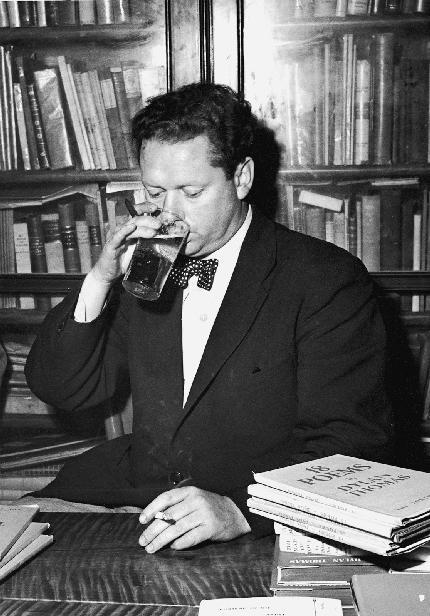

AT THE END OF

February, Dylan Thomas, on his first reading tour in America, visited Westport. Poet John Malcolm Brinnin, director of the Poetry Center at the YM-YWHA (now the 92nd Street Y), was his escort in the New York area. Brinnin, who had idolized Thomas ever since reading his first published poems sixteen years earlier, was taken aback by the poet’s obvious ill health, unpredictable behavior, and prodigious alcohol consumption. As soon as his morning flight landed, Thomas headed to the airport bar for a double scotch and soda. His eyes were bloodshot, his teeth broken and brown with tobacco stains, and his body racked with a cough so violent that he sometimes vomited on the street. He would pass out with a lit cigarette in his hand, coming to only when it burned his fingers. At the literary parties to which Brinnin brought him, he made passes at women aggressively and indiscriminately; once he grabbed the writer Katherine Anne Porter, then nearly sixty, and hoisted her up in the air. Yet at his public events, where he read his own works as well as poems by Yeats, Hardy, Auden, and others, Thomas enthralled audiences with his hypnotic voice.

Thomas spent a few days at Brinnin’s home in Westport, and one afternoon the two men were invited to the Hymans’ for cocktails. After dinner at a local Italian restaurant, the group returned to Indian Hill Road to watch boxing on television. Jackson and Thomas began a game of

imagining plots for murder mysteries, of which they were both devotees, and tried to outdo each other in gruesomeness. Then Thomas read some of his poetry. Brinnin is oblique about what happened next: “As usual, we stayed too late and drank too much and the evening ended gracelessly, with some of us out in the snow, and some of us silent before a dead television set.” When they got back to Brinnin’s house, around three o’clock in the morning, Thomas was so drunk that Brinnin literally had to push him up the steps to the front door, where he refused to enter. “Now you know exactly what you’ve brought to America,” he told Brinnin.

Jackson and Thomas had some kind of intimate encounter that evening, the details of which are unclear. Brendan Gill gives an account of the scene in his gossipy memoir

Here at the New Yorker

, which serves mainly as an example of the rumors that spread about that night. (The book includes other unkind and possibly apocryphal stories about Jackson; Gill’s section on her opens, bizarrely, “Shirley Jackson Hyman wrote under her maiden name.”) According to Gill, Jackson and Thomas (whom he describes as “a tubby little man, with thinning hair and brown teeth with holes in them”) were both drunk when he made a pass at her. Jackson jumped up and ran through the living room, past Hyman watching television, with Thomas following her. They did several circuits around the house, up the front stairs and down the back, until Hyman—“irritated at having his view of the ball game repeatedly interrupted by the great beasts jogging past him”—grabbed Thomas by his belt, bringing him down.

Brinnin told Paul Ferris, Thomas’s biographer, that Gill’s account was untrue. In his version, he went outside, drunk, to vomit and saw Thomas and Jackson “fooling about” in the snow: he heard “squeals of girlish laughter, his or hers,” and went back into the house. As they drove home, Brinnin says, Thomas confessed that the cold night air had made him impotent. Brinnin clearly thought alcohol was also a factor.

Jackson’s version is different still. In an untitled fragment, a woman named Margaret—the name Jackson also used in “The Beautiful Stranger” and “Pillar of Salt”—is tipsy and bored by her guests, a pretentious writer and his prissy wife (perhaps stand-ins for the Gills). As the writer drones on about Kafka, she slips out, tired of putting on a

“bright alert face.” On the porch she finds another man, smoking a pipe. Though they have hardly spoken previously, she feels an uncanny affinity with him.

Dylan Thomas in New York City, c. 1950.

“are you afraid sometimes?” margaret asked him.

“not very often.”

“i’m afraid of staying,” margaret said. she saw him nod, against the light from the door. encouraged, she went on, “i’m afraid of being with myself so much. i forget to look outside.” . . .

they were quiet for a minute and then margaret turned and put her arms around his neck; oh, god, i’m drunk, she thought for a minute and then it was gone. . . .

he had put one arm around her in return; the other hand was holding his pipe; when he laughed and tightened his arm around her she was appalled and thought, oh god, oh god. . . .

“what am i doing?”

“you are sitting here,” he said carefully, as though choosing his words to convey an exact meaning, “in a position of great comfort, me with my arms around you and you with your arms around me. although as a gesture it was completely meaningful, as an attitude it is still noncommittal.” . . .

margaret laughed, thinking oh god, oh god. “i’m not even afraid,” she said.

“no.”

“i won’t ever

be

afraid.”

“no.”

“can you cross a border line as easily as that?” margaret asked, wondering.

“easily.”

“and never go back?”

“never.”. . .

she began to laugh again helplessly, shaking his arm and the porch rail. she put her head against his shoulder and was lost, slipping slowly into the darkness of not knowing, and not caring, and not wondering, and not believing.

On her way inside, she encounters the pretentious writer’s wife, who tells her that she saw what Margaret was up to and assures her that she will not mention it to Margaret’s husband. “there ought to be a name . . . for a woman who has to find someone to mind her children when she wants to be unfaithful to her husband,” Margaret volunteers, self-deprecatingly. She returns to the cocktail party. “i have a secret, she was thinking, sitting in her chair looking unafraid at the people around; i have a brave, brave secret locked in, locked in, with me.”

The depiction of the encounter in Jackson’s story is far less tawdry than Gill’s story of the “great beasts jogging” around the house or Brinnin’s report of Jackson and Thomas in the snow. It also seems

more plausible, especially considering Brinnin’s assessment of Thomas’s physical condition. “I’m afraid of staying,” Margaret tells the man in the story. Despite her love for her house, her children, even her husband, there was a part of Jackson that longed for escape. Escape might come in the magical form of James Harris, who speaks to Clara in “The Tooth” of a place “[e]ven farther than Samarkand . . . the waves ringing on the shore like bells.” Escape could come, more prosaically, through mental release, with or without alcohol: elsewhere in the fragment, Margaret cherishes “the little moments of unconsciousness that came so easily and went with a breath; they were precious to her in a way that moments of acute awareness never were; drunk, perhaps, or lost running, the beautiful departure of self, slipping away to tend to things of its own, and then the abandonment of heart and mind without its monitor.” And here it comes in the form of a beautiful stranger, a mysterious man on the porch who is content to sit with his arm around her, speaking quietly. But it is never without danger—of people gossiping, of random cruelty, or of one’s own dissolution.