Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (45 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

The aftermath of the accident was nearly as difficult for Shirley as the initial trauma had been. The morning afterward, while she and Stanley were waiting at home for word from the hospital, an insurance agent representing the car’s driver (a “sweet-faced old lady,” as Shirley remembered her) visited them: “he remarked that of course everything would be all right, and that of course the important thing was saving the boy’s life, and that right now of course no one wanted to talk about insurance or such. . . . in our haste to reassure the sweet-faced old lady we practically acquitted her of blame.” Later she learned that the true purpose of the visit had been to elicit “incriminating statements” from her and Stanley in their distracted state, to ensure that they would not be able to prove that the “sweet-faced old lady” had been at fault. The experience left her demoralized and disillusioned. “if it is your child she injures next, please profit by our experience,” she wrote in an unpublished polemic about the experience. “leave your child lying on the street, go as quickly as you can to gather witnesses who will if necessary extend the truth a little, make sure that the police and the bystanders realize clearly that none of this was your child’s fault, and announce clearly and distinctly before the child is moved that you intend to sue; if your child dies, you will very likely win.”

The next month brought a hurricane to the celebrated Gold Coast. “half our town is gone. . . . all of the beach and the beach houses are either submerged or on their way out to sea,” Shirley reported. She would joke about Laurence—finally out of bed—having brought it on by asking the birch tree out front for a dime’s worth of wind. But it was a disaster: three hundred books they had been storing in the garage were ruined, along with the sandbox, the playhouse, and various of the other small pleasures that she had been so pleased to accumulate.

Laurence’s thumb was not healing properly; it would have to be broken again and reset. The cough that had been plaguing Joanne was finally diagnosed as asthma, which the doctor thought was partly

psychological, a result of her distress over Laurence’s condition. “we are thinking of hiring a resident doctor to take care of all of us, since it seems to be a full-time job,” Shirley wrote to her parents. And the sweet-faced old lady’s insurance company declined to pay Laurence’s hospital bills; Shirley and Stanley had to sue her in order to recover any money. Shirley’s only consolation was that somehow, in the midst of all this, she had managed to finish her second novel.

HANGSAMAN

IS A WEIRD

, rich brew of autobiography and fantasy, combining elements of Jackson’s unhappy years at the University of Rochester, the social culture of Bennington College, her marriage to Hyman, and literary allusions ranging from

Alice in Wonderland

to Victorian pornography; even Emma’s crack-up went into the mix. The title comes from another Child Ballad, “The Maid Freed from the Gallows,” popularized as a blues song known as “Gallows Pole” or “Hangman Tree”: “Slack your rope, Hangsaman, / O slack it for a while, / I think I see my true love coming, / Coming many a mile.” In the song, a young man or woman about to be hanged is visited by various family members: “Father, have you brought me hope, have you paid my fee? / Or have you come to see me hanging on the gallows tree?” All refuse: they have come to watch the hanging. Only true love offers salvation.

On the surface,

Hangsaman

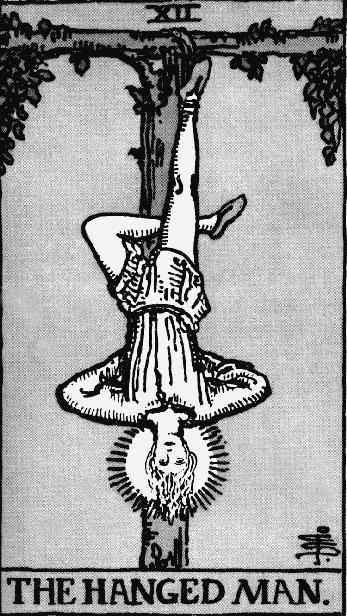

is the story of Natalie Waite, one of the many precocious children in Jackson’s fiction, whose similarities to her creator have already been discussed. Her name references the occultist Arthur E. Waite, who wrote a guide to the tarot that was popular in the early twentieth century and also collaborated with the artist Pamela Smith on a widely used tarot deck. (When Jackson read tarot cards, she usually used an older version, known as the Tarot of Marseilles, but she was familiar with the Waite-Smith deck.) The Hanged Man is one of the most important cards in the deck, with a complex iconography. The card depicts a man hanging by one leg from a T-shaped tree, the other leg crossed behind him to form an upside-down figure 4; as Waite observes, the compulsion to turn the card so that the man is right-side up is virtually irresistible. Its appearance in a tarot reading is said to

indicate not a death sentence, but the possibility of spiritual transformation. Waite notes that the figure’s face “suggests deep entrancement, not suffering,” and that the image as a whole evokes “life in suspension.” It is the most mystical of all the cards, he writes: “He who can understand that the story of his higher nature is imbedded in this symbolism will receive intimations concerning a great awakening that is possible, and will know that after the sacred Mystery of Death there is a glorious Mystery of Resurrection.” T. S. Eliot, who mentions the Hanged Man in

The Waste Land

, seems to have understood the card along metaphorically similar but pre-Christian lines, associating it with the symbol of the Hanged God in Frazer’s

Golden Bough

. As Frazer tells it, the people of ancient Phrygia, who worshipped a god of vegetation named Attis, believed that they maintained the fertility of the land with an annual ceremony reenacting the god’s death and resurrection.

The reference to the card in the novel’s title suggests that a spiritual transformation will take place therein. The book’s earlier title,

Rites of Passage

, may also refer to the ancient initiation rituals Frazer describes, which Jackson would have known both from her own reading of

The Golden Bough

and from Hyman’s recent intense immersion in myth and

ritual criticism. Applying unsuccessfully for a 1948 Guggenheim Fellowship to support the book, Jackson described it as “a novel with contemporary setting centering around the ritual pattern of the sacrificial king.” (The fellows in fiction that year included Saul Bellow, Elizabeth Hardwick, and J. F. Powers.)

The Hanged Man tarot card, from

The Pictorial Key to the Tarot,

by Arthur Waite

.

When the novel begins, Natalie is about to go away to college, leaving behind an unhappy home: her father is controlling and insensitive, her mother smothering. In the first chapter, Mr. Waite, a book critic who writes for “The Passionate Review,” critiques a writing assignment he has given his daughter. The exercise, it turns out, was to write a description of him, which Natalie has done with astonishing candor: “He seems perpetually surprised at the world’s never being quite so intelligent as he is, although he would be even more surprised if he found out that perhaps he is himself not so intelligent as he thinks.” Rather than being offended, her father applauds her precise language, then offers a few self-serving criticisms. “You overlook one of my outstanding characteristics, which is a brutal honesty which frequently leads me into trouble. . . . My honest picture of myself has led me to aim less high than many of my contemporaries, because I know my own failings, and as a result I am in many respects less successful in a worldly sense.” Coming on the heels of

The Armed Vision

, this description reads so clearly as a caricature of Hyman that some of his friends commented on the resemblance.

As the chapter progresses through a garden party hosted by the Waites, Jackson’s attack grows more pointed. Books set out for the guests’ enjoyment include

Ulysses

,

The Function of the Orgasm

(a then fashionable volume by the psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich, whose theories about channeling sexual energy via an “orgone box” attracted Bellow and other intellectuals of the period),

Hot Discography

(a catalog of jazz recordings), the abridged edition of

The Golden Bough

, and an unabridged dictionary—a brief and ludicrous snapshot of Hyman’s interests. Mr. Waite dresses for the party in a “fuzzy tweed jacket” that makes him look “very literary indeed. . . . It was almost equivalent to a brace of pistols and a pair of jackboots; Mr. Waite was arrayed for his own interpretation of a street brawl.”

The novel’s portrayal of the relationship between Mr. Waite and

his wife—in her attitude toward her daughter she is all Geraldine, but she sometimes speaks in Jackson’s voice—is even more damning. The kitchen, which her husband never enters, is the only room in the house that Mrs. Waite feels is truly her own. In a bleak moment, she confides her frustration to her daughter in a speech reminiscent of the bewildered housewife in “Got a Letter from Jimmy”:

I always used to wonder how people made happy marriages and made them last all day long every day. . . . Don’t ever let your husband know what you’re thinking or doing, that’s the way. . . . When I met your father he had a lot of books that he said he read, and he gave me a Mexican silver bracelet instead of an engagement ring . . . and I thought being married was everything I wanted. . . . Don’t ever go near a man like your father.

Natalie escapes from this poisonous environment the only way she can—mentally. In an early draft of the novel, she hears the devil Asmodeus speaking to her; in revisions, Jackson changed this literal possession to fantasies in which Natalie’s personality begins to divide. She imagines a detective repeatedly questioning her about the murder of her father, or a team of future archaeologists excavating the Waite house and coming upon her skull (“Male, I should say, from the frontal development”); later, she will write of herself in the third person. At the garden party she tries drinking as another form of escape—it is her first experience with alcohol—and the result is her disastrous, obliquely suggested sexual encounter in the woods with one of the guests.

After Natalie arrives at college, her disintegration continues. Her experiences there reflect Jackson’s early difficulties at Rochester, but the college is unmistakably Bennington, as Jackson acknowledged in an outline for the novel:

It was decided to construct the college buildings entirely of shingle and “the original beams”; it was supposed that modern dance and the free use of slang in the classrooms might constitute an aura of rich general culture. It was decided that anyone who wanted to

study anything should be accommodated, although gym was not encouraged. . . . It was unanimously voted that students should be allowed to drink, stay out all night, gamble, and paint from nude female models, without any kind of restraint; this, it was clear, would prepare them for the adult world. . . . The faculty members were to be drawn almost entirely from a group which would find the inadequate salary larger than anything they had ever earned. . . . A great deal was said about old English ballads.

Here Natalie meets Arthur Langdon, a well-regarded English professor, and his much younger wife, Elizabeth, one of his former students, who complains about her loneliness as a faculty wife and drinks heavily as consolation for his flirtations with others. Elizabeth is particularly tormented by a pair of students named Anne and Vicki, who flatter her husband’s ego and condescend to her. (Another distinctively Bennington detail: when Anne and Vicki throw a cocktail party, they serve gin in toothbrush glasses “confiscated from the common bathrooms, rinsed inadequately, and dried on other people’s bath towels”—no matching crystal here.) Only Natalie sympathizes with Elizabeth, leading her home when she is too drunk to walk by herself and trying to console her when she confesses, “Natalie, I want to die.”

The first sign that all is not well with Natalie comes when other girls in her dorm complain that things have gone missing—a dress, money, jewelry—and Natalie reflects on her own possessions: “if she had lost any clothes or jewelry she would hardly have known it, since she had worn the same sweater and skirt for a week.” Soon after, she becomes aware of the presence of “the girl Tony,” who is another of her mind’s projections, although that may not be immediately clear to the reader. Clues throughout that Tony is unreal, including a scene in which Natalie goes to sleep in Tony’s bed but wakes up in her own, are subtle. One night she is awakened: Tony appears naked at her bedside, takes her hand, and leads her to a room filled with all the things that have been stolen, chattering about the little girl who has come to sleep in her bed—a scene reminiscent of Jackson’s experience of being woken by the babbling Emma. Natalie runs away in fear, but she cannot resist

Tony’s pull. Together they play solitaire with tarot cards, “old and large and lovely and richly gilt and red”; they sleep in the same bed, “side by side, like two big cats”; and eventually they run away, taking a bus to a town that loosely resembles Rochester.

Now the atmosphere grows still more unreal. Natalie has passed through the looking glass; she quotes a line from Lewis Carroll, “Still she haunts me phantomwise.” She sees tarot symbols encoded in the signs and shop windows; at a cafeteria, she and Tony meet a man with one arm. This section explicitly draws upon Jackson’s wanderings around Rochester with Jeanou, with whom she was still corresponding sporadically; her diary from her first year of college even mentions a “strange, one-armed man” she saw in a café. Finally, in the woods by an abandoned fairground, Natalie believes, to her horror, that Tony is trying to seduce her. Of course, if Tony is not real, this is impossible. But it provides the push Natalie needs to shock herself back into sanity. She returns to college feeling she has survived a trauma. “As she had never been before, she was now alone, and grown-up, and powerful, and not at all afraid.”