Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (47 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Neither Trilling nor Aldridge mentioned a novel that had just appeared a few months earlier, one that refuted both their arguments: Ralph Ellison’s

Invisible Man

, which Hyman had had such an important role in shaping. Steeped in mythology as well as the history of the African-American experience in the United States, Ellison’s novel—the darkly surreal coming-of-age story of a young black man struggling against the perversities of racism—was no fashion drawing for the sophisticated modern mind, but a profound investigation of a human being as marginal to society as Natalie in

Hangsaman

or the lost women of Jackson’s earlier stories. It’s notable that Aldridge failed to mention race as a social taboo, since—as Ellison demonstrated—it was in fact still a potent source of tension. (Homosexuality, also not on Aldridge’s list, was obviously another.) But the critics who embraced

Invisible Man

nearly unanimously—it won the National Book Award in 1953—tended to see it less as a novel about black identity than as a depiction of an American Everyman. “What language is it that we can all speak, and what is it that we can all recognize, burn at, weep over, what is the stature we can without exaggeration claim for ourselves; what is the main address of consciousness?” asked Saul Bellow in

Commentary

, praising Ellison for not adopting a “minority tone” in his writing.

The Adventures of Augie March

(1953), Bellow’s breakthrough novel, represented his own attempt to write a coming-of-age story that was at once identifiably Jewish and generically American.

It was easier for critics of the early 1950s to regard as universal a story about a black man or a Jewish man than a story about a woman. But telling women’s stories was—and would always be—Jackson’s major fictional project. As she had in

The Road Through the Wall

and the stories of

The Lottery

, with

Hangsaman

Jackson continued to chronicle the lives of women whose behavior does not conform to society’s expectations. Neither an obedient daughter nor a docile wife-in-training, Natalie represents every girl who does not quite fit in, who refuses to play the role that has been predetermined for her—and the tragic psychic consequences she suffers as a result. During the postwar years, Betty Friedan would later write, the image of the American woman “suffered a schizophrenic split” between the feminine housewife and the career woman: “The new feminine morality story is . . . the heroine’s victory over Mephistopheles . . . the devil inside the heroine herself.” That is precisely what happens in

Hangsaman

. Unfortunately, it was a story that the American public, in the process of adjusting to the changing roles of women and the family in the wake of World War II, was not yet ready to countenance.

The first printing of

Hangsaman

did not sell out. Fortunately, Jackson already had another book in the works. This one would be a best seller.

11.

BENNINGTON,

LIFE AMONG

THE SAVAGES

,

1951–1953

I have never liked the theory that poltergeists only come into houses where there are children, because I think it is simply too much for any one house to have poltergeists

and

children.

—“The Ghosts of Loiret”

I

T IS THE ENDURING QUESTION OF SHIRLEY JACKSON’S CAREER

. How could she simultaneously write the dark, suspenseful fiction that would define her legacy—“The Lottery,” “The Daemon Lover,”

The Haunting of Hill House

,

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

—and the warm, funny household memoirs that brought her fame and acclaim in the 1950s but have largely been forgotten since? With the publication of

Life Among the Savages

and its sequel,

Raising Demons

, a wide audience of enthusiastic readers gobbled up the adorable (and often embellished) antics of Laurie, Jannie, Sally, and Barry, recorded by their flustered, bemused mother. Even reviewers who had not found

Hangsaman

willfully obscure marveled that a writer whose last novel had featured sexual assault and schizophrenia was now spinning madcap

I Love Lucy

–style yarns about a visit to the department store, the night all the family members (even the dog) wound up in the wrong beds, or the time the furnace and the car both died while her husband was away on a business trip. This was a novelist who had once referred to herself as “this compound of creatures I call Me”; still, it was a generous range. “The Lottery” was as different from

Savages

, one reviewer remarked, as “a thunderstorm from a zephyr.”

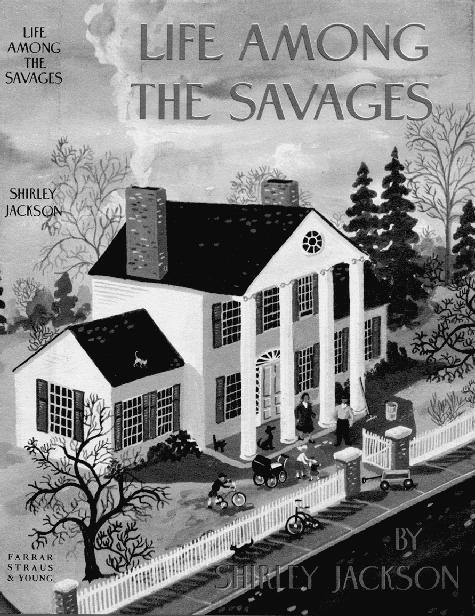

The jacket for

Life Among the Savages

(1953). The house is modeled on the Hyman house on Prospect Street in North Bennington.

But

Savages

is recognizably a book by Jackson, owing not least to its gentle touch of the macabre. The book concludes with a document purporting to show evidence of a poltergeist in the house—written in a parody of Glanvill—and one of the family cats is called Shax, after the demon. An early draft went further, with an episode in which Jackson

is visited by a ghostly former resident of the house they have just moved into. But in the final version she toned this down, choosing instead to suggest a homier mode of the uncanny by claiming that the furniture left behind by the previous owners had its own opinions about its arrangement: “No matter how much we wanted to set our overstuffed chairs on either side of the living room fireplace, an old wooden rocker . . . insisted upon pre-empting the center of the hearth rug and could not in human kindness be shifted.” Although Jackson states matter-of-factly in the book that she has “always believed in ghosts,” the house in

Savages

is haunted only in the way that all houses are haunted: with the memories created by the family who call it home, along with the faint impressions left by those who have gone before.

Like virtually all humor writing,

Savages

straddles the line between fiction and fact; it is autobiographical but not necessarily true. Shirley listened closely to her children’s talk—she and Stanley loved to repeat their latest hilarities, and notes in her files show that she jotted down the children’s best lines as inspiration. The Hyman children affirm that many of the stories are based on real-life incidents, some of which appear in very similar form in Shirley’s letters to her parents. Apologizing for a long delay between letters, she once wrote that “the reason i always think i have written you is because i write the same material in stories; if i sent you the first drafts of all my stories you would have twice as many letters.” Geraldine, not surprisingly, loved the household stories so much that she would thumb through all the women’s magazines at the newsstand to be sure she hadn’t missed one. “It is just like a visit with you and Stanley and the children to read one of your stories,” she wrote with pleasure from California, though she would also carp at her daughter for her too honest depiction of her “helter skelter way of living.”

In her literary fiction Jackson zeroed in on the moments of greatest confusion, discomfort, or depravity in her characters’ lives, but in

Savages

she omitted the painful bits to focus on the cheer. In her own way, she was finally following through on that long ago admonishment to “seek out the good . . . rather than explore for the evil.” Many of the drafts reveal rawer versions of episodes that would eventually be buffed and polished for public consumption. Telling the story of Laurence’s

accident, for instance, Jackson conveys only a hint of her own anguish and certainly nothing of her cynicism about the sweet-faced old lady. Instead, that episode in

Savages

begins with him coming home from the hospital safely healed, full of pride over his ordeal, and eager to hear all the gruesome details (“Was there a lot of blood?”). As she had been telling herself—with Hyman’s encouragement—since the earliest stages of her career, “an accurate account of an incident is not a story.” Creative transformation was always required.

It took time for Jackson to make her way into this genre: a few early attempts at

New Yorker

–style humor fell flat. As with her fiction, she found true inspiration after the children’s arrival. Starting with “Charles,” the story about Laurence blaming his own kindergarten misdeeds on an imaginary classmate, Jackson discovered a lucrative market for her household stories in women’s magazines such as

Good Housekeeping

and

Woman’s Home Companion

, as well as in general-interest publications such as

Harper’s

and

Collier’s

. In these pieces—many of which were incorporated into

Savages—

Jackson essentially invented the form that has become the modern-day “mommy blog”: a humorous, chatty, intelligently observed household chronicle. Before Jean Kerr’s

Please Don’t Eat the Daisies

(1957) or Erma Bombeck’s

At Wit’s End

(1967), she brought something of an anthropologist’s eye to her tribe of “savages,” treating “the awesome vagaries of the child mind,” as one reviewer put it, with a combination of “clinical curiosity, incredulity, adoration and outrage.” (In a line reminiscent of “The Lottery,” the same reviewer noted that “[t]his tribe lives among us; its jungle is everywhere.”) No one had written about life with children in quite this way before.

Jackson made it look easy. Her files brim with fan mail from admiring readers, many of them mothers who were aspiring writers in search of advice. Some wondered at Jackson’s ability to get anything done while caring for four children—which also mystified some of her friends. “She not only had a working life and a life with children, but a very demanding husband and an enormous household,” recalls Midge Decter. (In “Fresh Air Diary,” Jackson confesses her impatience with such comments: “This is a remark I have never been able to answer,” she muses after a weekend guest wonders how she can take care of her

children and still find time to write.) Others were more critical of their own deficiencies. “Why, I asked my blundering self, can’t I produce something

that

good?” asked one reader, recognizing the wealth of material provided by just about any brood of kids. Jackson occasionally wrote back, suggesting practical strategies such as planning out a piece before sitting down at the typewriter and, not surprisingly, ignoring the housework to carve out more writing time. “Despite interference from the children, I manage to get stories written about them,” she joked to her agent after Laurence suffered yet another minor calamity that required stitches.

Its deceptive simplicity notwithstanding, this form required every bit as much control as any of Jackson’s writing. Her household stories take advantage of the same techniques she developed as a novelist: the gradual buildup of carefully chosen detail, the ironic understatement, the repetition of key phrases, the instinct for just where to begin and end a story. Her style, too, is as painstakingly refined as in her serious fiction. In an episode describing the last day of summer vacation, Jackson tries to generate enthusiasm in Laurence and his friends by telling them she always loved school. In an early draft, she reports their reaction as follows: “there was nothing for any of them to say in the face of that bald lie. they sat and stared at me, deadpan.” In the final version, these lines, now a single sentence, acquire a new pungency: “This was a falsehood so patent that none of them felt it necessary to answer me, even in courtesy.”

Even more than her style, Jackson’s voice makes these stories compulsively readable: many of the fan-mail writers looked upon her as their new best friend. The persona she created was both charming and approachable, a mother at once loving and perennially distracted—perhaps by the stories she was planning as she chauffeured her children to school or heated a can of soup for lunch. She clearly would rather be on the floor reading to her children instead of dusting around them, but she might like best of all to check into a hotel by herself, with housekeeping and room service. Not only has she no talent for housework (“Not for me the turned sheet, the dated preserve, the fitted homemade slipcover or the well-ironed shirt”), but even the maids she hires turn out to be

alarmingly incompetent: one disappears shortly before her parole officer shows up, while another turns out to be a born-again Christian who ices cookies with the lettering “Sinner, Repent.” She admits to a “pang of honest envy” as her husband departs for a business trip; when the children misbehave in public, she disguises her frustration by smiling “sweetly and falsely.”

Just as motherhood is not sentimentalized nor idealized, neither are the children. Sometimes, Jackson admits, she finds herself “open-mouthed and terrified” before them, “little individual creatures moving solidly along in their own paths.” Laurence (always called Laurie in the stories, as he was in real life as a child), restless and cheeky, despises school and relishes any kind of practical joke; if a phone call comes for Jackson during breakfast, he is apt to embarrass her by telling the caller she is still asleep. (In an author’s note, Jackson says he explicitly requested that she include “Charles” in the book.) Joanne, called Jannie, is adorable and a little bit wacky, refusing to go anywhere without a troop of imaginary friends and insisting that they be addressed by name, offered cookies, and read to. Sarah (Sally), at around age three, enters “with complete abandon into a form-fitting fairyland,” subjecting her mother to “tuneful and unceasing conversation . . . part song, part story, part uncomplimentary editorial comment.” Standing on her head in the backseat of the car—the only position in which she consents to ride (this was the pre-seat-belt early 1950s)—she sings, “I’m a sweetie, I’m a honey, I’m a poppacorn, I’m a potato chip.” “When I ask you ‘What’s your name?’ you must say ‘Puddentane,’ ” she commands her unobliging older brother. After an afternoon excursion to a farm, she regales her siblings with a tale of watching giants roast marshmallows over a campfire. Jannie turns out to be more skeptical than her mother, who finds Sally’s stories more disconcerting than she cares to admit: