Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (50 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

But Jackson had to put her new novel aside to to finish

Savages

, which she managed to do just after the new year. She sent the manuscript off on January 5, 1953, after an anxious Christmas spent in Fromm’s “dismal little house,” uncertain about what lay in store.

MARGARET FARRAR RECOGNIZED

the potential of

Savages

as soon as she saw the rough draft. The book was “completely delightful and entertaining reading—not Shirley on a broomstick at all,” she reported to her colleagues. To Jackson she was even more enthusiastic: “Every time I think of the ‘savages’ I feel better about life. It’s a gem of a book.” The only editor with reservations was new partner Stuart Young, who found the stories “warm and affectionate and reasonably pleasurable reading” but didn’t think they would sell. Fortunately, both John Farrar and Roger Straus disagreed. “With the proper enthusiasm and promotion,” Farrar predicted, the book would “far outsell anything Shirley has done.” To Jackson’s chagrin, they decided to delay publication until June 22, 1953, to take advantage of the summer market for lighter books. “It seems too bad in a way that it takes longer to have a book than a baby, but that should be excellent timing for it,” Margaret Farrar—who, if not

an equal partner with her husband, had significant editorial responsibilities—reassured Jackson. The subtitle would be

An Uneasy Chronicle

.

Jackson always had a litany of complaints about the way Farrar, Straus handled her books, and

Life Among the Savages

was no different: she found the jacket copy inane, the page proofs didn’t reach her on time, the advertising budget was too small. Despite these problems, it was clear well before publication that the book would be an enormous success. In March, the Family Book Club bought rights to

Savages

for $7500, split between Jackson and the publisher; another excerpt was sold to

Reader’s Digest

for $5000. Even the children got excited about the book, especially when they learned that their photograph would be on it instead of Jackson’s—a creative compromise. She hung the jacket on the kitchen wall, “so they can admire themselves while they dine.” Their own name for it was “Life Among the Cabbages.”

By publication day, advance orders had already driven the book into a third printing. Orville Prescott kicked things off with a rave in

The New York Times

, calling

Savages

“the funniest, the most engaging, and the most irresistibly delightful book I have read in years and years.” Jackson was so delighted that she wrote him a thank-you note. The book debuted on the July 12

New York Times

best-seller list at number 16, selling around five hundred copies a day. (Also on the list that summer was Norman Vincent Peale’s

The Power of Positive Thinking

, one of the first blockbuster self-help books.) “Staggered” by the news, Jackson gloated that Hyman now had no basis for complaining, as he did whenever he discovered her writing a long letter, that she ought to be spending her time on stories: “when i am making three hundred dollars a day just sitting around he can’t open his mouth whatever i do.” Geraldine, thrilled that her daughter had finally made the best-seller list, felt that her own taste was vindicated: “Funny how people like the amusing ones and will read them when a serious novel seems to leave them cold.” By the end of August,

Savages

had risen to number 8—one notch above the Revised Standard Version of the Bible. Jackson was so buoyed by her success that even a nasty letter from a reader did not trouble her. “If you don’t like my peaches, don’t shake my tree,” she wrote back saucily.

For once, most of the reviewers at least understood what Jackson was

trying to accomplish, even if they didn’t all approve of her turn toward the quotidian. But there was a notable gender divide. Male reviewers—still the majority, even for a book about child rearing—tended to find the children rambunctious and the household unpleasant. “Cute Kids, but Mommy’s Better When She’s Sinister” was the headline in the

New York Post

, whose reviewer called Jackson’s humor strained and the children “very cute, very bright and very bad.” In his column in the

New York World Telegram

, Sterling North, who would achieve renown for his young-adult best seller

Rascal

(1963), adopted a condescending tone. “There is no reason, I suppose, why a mother should not write at some length about her four children (ages one to ten), about the cat named Shax and the dog named Toby and the continuous bedlam in what must be one of America’s most chaotic households. But when that mother is a prose stylist of the caliber of Shirley Jackson it is something of a shock to read such ephemeral fluff,” he sniffed.

Barry, Sarah, Joanne, and Laurence, photographed for the jacket of

Life Among the Savages.

Women, on the other hand, responded to the familiarity of the setting: for the first time, they saw their own travails depicted in literature. “Never, in this reviewer’s opinion, has the state of domestic chaos been so perfectly illuminated,” wrote Jane Cobb in

The New York Times Book Review

, where she was identified as “a free-lance critic with her own share of domestic responsibilities.” Margaret Parton, in the

New York Herald Tribune

, wrote that “it is the very familiarity of the material which makes it such pleasant reading—emotional catharsis, no doubt.” For these readers, Jackson wasn’t introducing the unfamiliar customs of a foreign tribe. She was describing their own daily routine, though with the ironic distance that is virtually impossible to achieve regarding one’s own household.

Not all the critics agreed that

Savages

was a departure for Jackson. Joseph Henry Jackson of the

San Francisco Chronicle

, who had been following her career closely since

The Road Through the Wall

, found

Savages

, in its own way, as uncanny as Jackson’s other work, in part because of the “chilling objectivity” with which she depicted the children’s fantasy life: “any parent will recognize the other world into which children can withdraw at an instant’s notice, and the helplessness of the adult faced with it.” In the most perceptive review of the book, Edmund Fuller, a biographer, critic, and novelist whose fictionalization of the life of Frederick Douglass was remarkable for its time, also recognized the continuity among Jackson’s works. “Shirley Jackson has built her reputation on a combination of the fantastic and the macabre added to what is actually as clear-eyed and minutely observant a scrutiny of contemporary life as any fiction writer is offering,” Fuller wrote. He judged

Savages

her best work yet, establishing Jackson as “a humorous writer second to none, in a vein not unlike James Thurber or E. B. White, at their best.” (A few years later, a reviewer of

Raising Demons

would call Jackson a “female Thurber.”) She had “pinned down the contemporary middle class intellectual couple with young children definitively—the happenings, the sayings, the crisis. . . . It sounds like home.”

As always, the publicity was Jackson’s least favorite part. She had a disastrous interview with Mary Margaret McBride, the host of a popular women’s advice radio show. Jackson was insulted when McBride announced at the start of the interview—live on the air—that she was unfamiliar with

Savages

: “i thought she might at least have read my book, so i said something to that effect.” After the interview, McBride offered an attempt at apology, confessing that it was the first failure

she had ever had. “You’re such a nice woman and I just hope I didn’t scare you to death,” she wrote to Jackson. Later Jackson would say that McBride had called her “the most uncooperative person she ever had on her program.” Geraldine wasn’t amused by her description of the debacle. “You

must

learn to hold your temper,” she scolded.

The book’s sales more than compensated for such ordeals. The success of

Savages

finally allowed Shirley and Stanley to buy a house of their own.

MORE THAN HALF A CENTURY

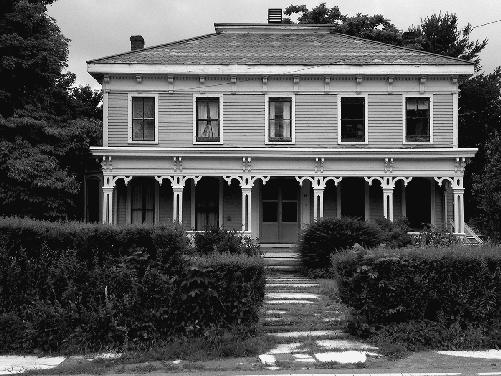

after she last lived there, 66 Main Street in North Bennington is still known as the Shirley Jackson house. Fifty years old when the Hymans bought it, in September 1953, it is a handsome, solid two-story wood-framed house a few blocks from the center of North Bennington, with seventeen rooms—“big, in that fine old high-ceilinged fashion,” Shirley described it—a barn full of pigeons, a driveway marked by two stone pillars (one perpetually crooked), and more than two acres of land. Shirley and Stanley were able to buy it for $15,000—“an extremely reasonable price”—because it had been divided into four apartments; two tenants were still in place. Within a few months, one had sneaked out in the middle of the night, owing a month’s rent; the other was in the midst of a divorce. For a while, Shirley and Stanley kept one of the apartments vacant to rent to friends—Ben Zimmerman and his wife, Marjory, were among those who lived there—but eventually they would take over the entire house.

Many say that 66 Main Street was the model for the ramshackle but dignified mansion in

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

. “It seemed to go on and on,” remembers Anne Zimmerman, who was born while her parents were living in the back apartment. There were two sets of stairs, front and back, and many of the rooms connected. To the right of the entrance was the front room, for watching TV and playing music, with Stanley’s study next to it. (Although he stopped drinking for a while around the time of the move, he nonetheless created a bar in the adjacent kitchenette.) To the left was the living room, where a tall Christmas tree would be erected every December, and the dining room, with a big

oblong table and bookcases. After Laurence, as an adolescent, developed a talent for carpentry, he built furniture for many of the rooms, including a gigantic cabinet that his parents used to display their collections: for Stanley, coins, antique weapons, and canes; for Shirley, china cats and an assortment of esoterica—“totems . . . and masks, and

objets

from a thousand anthropological capitals,” remembered Claude Fredericks, a poet, playwright, and translator who joined the Bennington faculty in 1961. On the wall, an Indian miniature was juxtaposed with an Azande

shongo

, or throwing knife; on the shelves, jostling for space, were a group of Australian

churingas

(elliptical totems); a terra-cotta statue of Silenos from ancient Thebes, its penis erect; an Iroquois rattle made from a turtle shell; a collection of Japanese netsukes; a ship harp from West Africa; and a Corsican vendetta knife. At the bottom of the staircase stood a statue of a Greek or Roman goddess holding a lamp. The town rumor mill transformed it into a statue of the Virgin Mary holding a beer can.

The house at 66 Main Street, where the Hymans settled permanently in North Bennington.

The kitchen, Shirley’s domain, ran the width of the house at the rear. On the ceiling she pasted silver stars of all shapes and sizes. Later,

when she was dieting, she would cover the walls with calorie counters. As her success mounted and the money began to pour in, she invested in improvements: new linoleum, a new Frigidaire “with a big freezing compartment and all sorts of silly little boxes for keeping butter and cheese and a slide for eggs to roll down and the inside all colored blue and gold,” a new pink dishwasher, yellow paint for the walls, turquoise cabinets. Eventually the exterior of the house would be painted gray with white trim; there would be new couches and curtains for the living room, brown leather chairs for the study, a new washing machine and dryer. Shirley’s beloved cats, too numerous to count, would wander in and out at will. Friends recalled hearing her talk to them as if having a conversation.

After the first tenant moved out, Laurence took over the upstairs back apartment. Joanne and Sarah had a suite of their own, two bedrooms with a shared library in between (Laurence built bookcases for them, too). Barry was next door, across from the master bedroom. Shirley had a study of her own next to the bedroom; at some point, probably in the late fifties, it became her bedroom as well. As the Hymans’ book collection expanded, Laurence built a library in the attic. (Stanley always removed the book jackets, which he thought were vulgar.)