Talking with My Mouth Full (19 page)

Read Talking with My Mouth Full Online

Authors: Gail Simmons

I’m not sure if my veal issue is a moral one or not. There are many other foods I will eat that are not much different, ethically speaking. Is lamb any different? It’s baby sheep. What about foie gras? Those geese and ducks being force-fed for my foie gras should bother me, but for some reason they don’t.

To me, veal always went under the category of unnecessary meat. As with tripe, I’m just not a huge fan. I’m not crazy about kidneys, either. But tongue, sweetbreads, and heart? Those hit the spot. Veal doesn’t have a distinctive enough flavor to make me want to eat it. It’s sort of meager beef. It doesn’t satisfy me in a way I can be satisfied from eating chicken, or duck, or beef, or lamb, or turkey. To me, it falls into a gray area, literally and figuratively. I learned to cook with it in culinary school, but if given the choice, I have to say: it skeeves me out. That’s a technical food term, by the way: “skeeves.”

Of course, try refusing any food in my mother’s home and see where that gets you. (Remember the zucchini incident?) When I was a kid and my mother would serve us veal, I would ask, “What is this?” “It’s chicken,” she’d always reply, just to get me to eat it. I’d take a bite. “No way, Mom. You are straight up

lying

to me.” I was no dummy.

What’s ironic is that my mother has her own irrational taste aversions. Recently, we were out for dinner and I was reviewing the wine list. I suggested a Spanish wine. (I love Spanish wines—Tempranillo, Albariño, I’ll take them all!)

In unison, my parents said, “We don’t drink Spanish wine.”

“What are you talking about?” I said. “It’s an entire country.”

“We tried Spanish wine twenty years ago and we just didn’t like it,” my mother replied. “We prefer to drink American or French.”

The truth is, my parents pretty much only drink sauvignon blanc. Yet my mother gets furious because I don’t eat veal.

So, we all have our subjective eccentricities. It’s no different from any other kind of criticism though. Book critics, music critics, and theater critics all bring their own preferences and personal contexts to bear. But all professional critics should have some training, in order to understand the foundations of what they’re judging, and should be able to look beyond their own personal tastes. I take every decision I make seriously and try to give every bite the respect it deserves. I couldn’t do my job if I had a long list of foods I dislike. The truth is, there are very few things I won’t try.

Actually, food is far easier to judge than, say, visual art, music, or dance, because there are very strict rules to cooking. I would argue that judging food is based 80 percent on science and technique, and 20 percent on instinct and artistic flair. Taste may appear totally subjective, but there are scientific forces at work determining how food should be cooked and prepared. It’s chemistry more than anything else.

Nonprofessionals tend to judge food based on their biases more than on science and proper technique. After years of paying close attention to other people’s cooking, I think I now assess food based much more on fact than on feelings. It’s not just about “I hate foie gras!” or “I’m not in the mood for duck today, so I don’t like this dish.” It’s that I now understand and appreciate how one plus one equals two—regardless of how I feel about the number two. The only way to learn these things is by eating and cooking. A lot.

When it comes to cooking meat, for example, there is a mathematical formula to doneness. Correct meat temperature can be measured to the degree. Snooty food snobs didn’t just make this stuff up. It’s a scientific reaction of protein and heat, and knowing when to serve meat at its optimum degree for tenderness and flavor. When you’re searing a steak, the pan needs to be very hot so that the natural sugars will caramelize and form a charred crust. This is also why you should never use olive oil to cook meat. Olive oil has a very low smoking point, as well as a very specific flavor. It burns easily and turns bitter, so you should use it only in dressings, as a finishing oil, or to lightly sauté or sweat quick-cooking vegetables. For higher heat or a longer cooking time, you need vegetable, canola, grape-seed, or peanut oil, which is also great for frying. Even better? Lard (yes, animal fat). The very best French fries are cooked in duck fat, which has a high smoking point and is a great heat conductor.

“Carryover cooking” is something chefs constantly refer to when discussing temperature. When you cook meat, the heat gets trapped inside the muscle. When you turn the heat off, the meat will continue to cook to a few more degrees. That’s why you should take it off the heat just

before

it reaches your ideal temperature. Meat should also rest before it is served. If you cut into it as soon as you take it off the heat, when the meat is still tense, all of its delicious juices and moisture will pour right out, along with all the flavor they contain.

Temperature is crucial in almost every facet of eating. Take cheese: you want to keep it in the fridge to preserve it, but you should always let it come to room temperature before eating it, to bring out all those subtle cheesy nuances, or you’ll be robbed of the gooey, runny pleasure of that creamy Brie de Meaux. In the same vein, there’s nothing I loathe more than cold butter. My biggest pet peeve at restaurants is when butter is served right out of the fridge, making it useless and impossible to spread. People are always worried about food spoiling, but honestly, there’s no reason not to leave a covered dish of butter out on the counter for a few hours before serving.

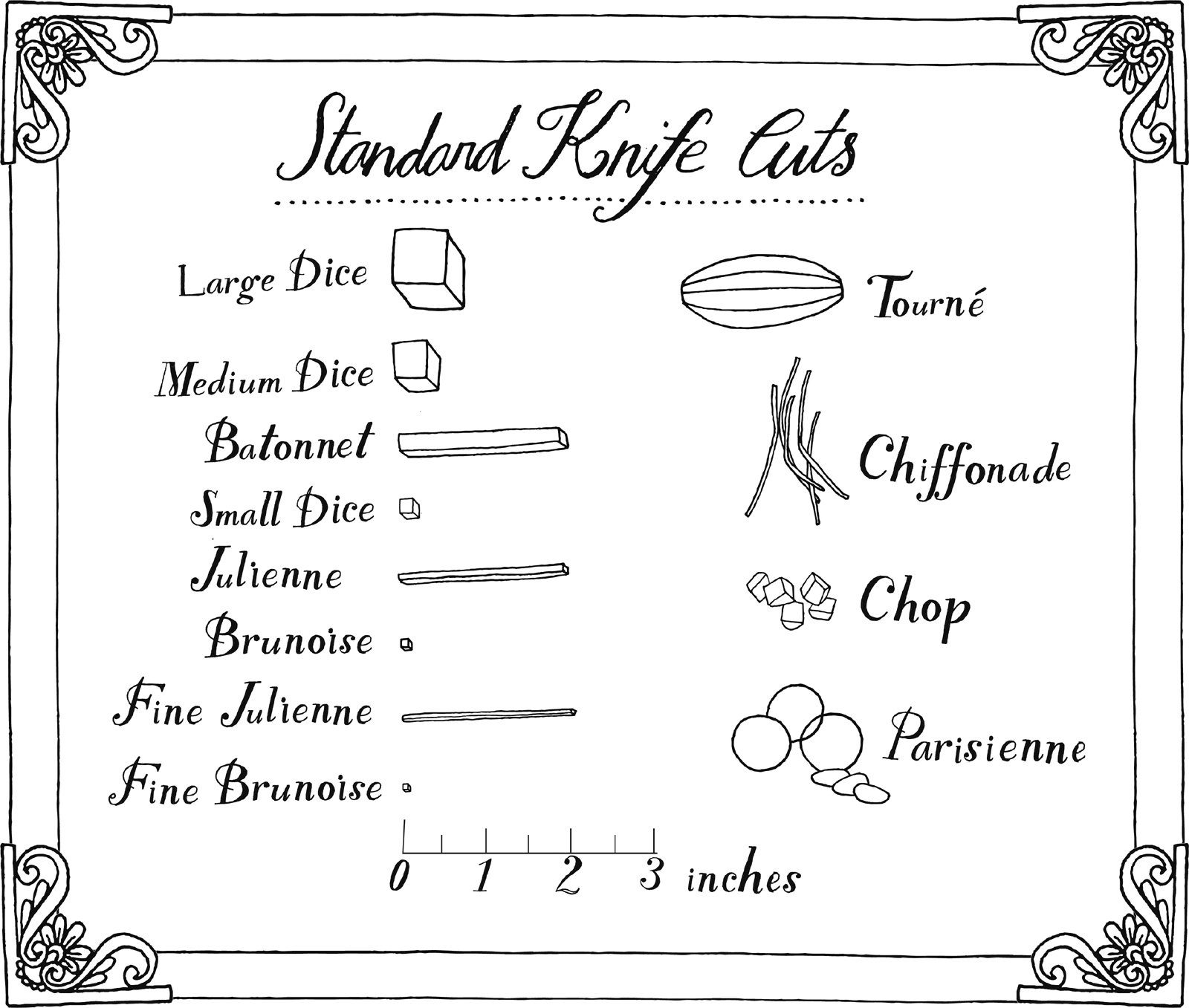

There is a science to knife skills, too. All foods have to be cut a certain way in order to cook properly and evenly. I’m a stickler for good knife work and can always tell when it’s sloppy. (I could watch the martial arts–like precision of a sushi master, as he wields a knife through fish, for hours on end.) Cutting ingredients correctly will bring out their best qualities, even after they’re cooked. For example, you should always slice a hanger or flank steak against the grain; this makes it far tenderer and easier to eat.

Understanding the purpose of different cooking methods is also essential in order to bring out the best flavor and textural qualities of food. Brisket is best when braised for a long time, as it is tough and lacking in marbled fat. You need to break down the muscle to tenderize it. For me, there are few things more delicious than slow-cooked brisket that’s been bathing in its own fragrant juices for hours on end. But other cuts of meat, like sirloin, are already tender and fatty to begin with. If you braise them, they’ll toughen or seize. These cuts should be grilled or pan-seared—quicker, more direct cooking methods. A well-trained chef knows how to treat each specific cut based on this underlying science.

Moreover, there are classic flavor profiles that always work well together (excuse the use of the term “flavor profile”; it always seems kind of pretentious to me, but it gets my point across). These are the specific flavors that ground a dish. A classic Italian flavor profile, for instance, is tomato, basil, and olive oil. It’s important for a cook to experiment and constantly look for new combinations, but there are proven standards at the foundation; as with color palettes in fashion and design, certain flavors simply make

sense

when they are eaten in unison. A good rule to keep in mind: if it grows together, it goes together—with respect to both season and geography.

The modernist cuisine movement (or molecular gastronomy, as it’s more commonly called) is dedicated to exploring the science of food, down to the microgram and degree. Its practitioners study and apply the chemical and physical reactions of ingredients. They demystify cooking processes by breaking them down to their scientific roots, and use modern technology to make cooking more efficient and precise.

What most people associate with modernist cuisine is foam, which is made by using a siphon. These days, anyone can buy a siphon for about $50. It pumps nitrous oxide into any liquid and thickening agent, transforming it into an aerated substance. Think of a Reddi-Wip canister, but instead of cream, you’re using Parmesan broth or tomato water, truffles or olive purée. The food comes out like Reddi-Wip, too, only lighter—more like spittle, or somewhere between spittle and Reddi-Wip. Foam allows you to add the essence of a flavor to a dish without adding texture or weight.

Of course, modernist cuisine isn’t just about foam. It has contributed so much to our contemporary understanding of cooking and of how food works—not to mention our gadget collections.

We need chefs who push our industry forward, even if only three out of every fifty ideas they think up actually work. These innovations are what will save us from eating steak and potatoes for the rest of our lives. But there’s a fine line between a new technique that enhances the way we cook and using a gimmick only for its cool factor. For me, the key question is: Does this innovation make food actually taste better, cook more efficiently, or look more beautiful? And if not, the next question is: Why bother?

With some modernist cooking, I can’t help but think something is lost—something that made me fall in love with cooking in my mother’s kitchen, watching those eggs turn from a liquid to a solid as I applied heat the old-fashioned way. I still love standing over a stove, seasoning meat, adding a bit of fat to a scorching hot pan, placing the meat in it, then touching it to gauge its doneness.

As a result of all this new equipment, are young chefs ever going to learn how to feel a piece of meat with their fingers to test if it’s done? With techniques like sous-vide—by which food is cooked in airtight plastic bags, immersed in water that can be adjusted to a fraction of a degree—you lose the immediacy of standing over a fire, and the expression of individuality in your food. On the other hand, you gain precision and consistency. It’s sort of like cloning. Efficient? Yes. Soulful? Not really.

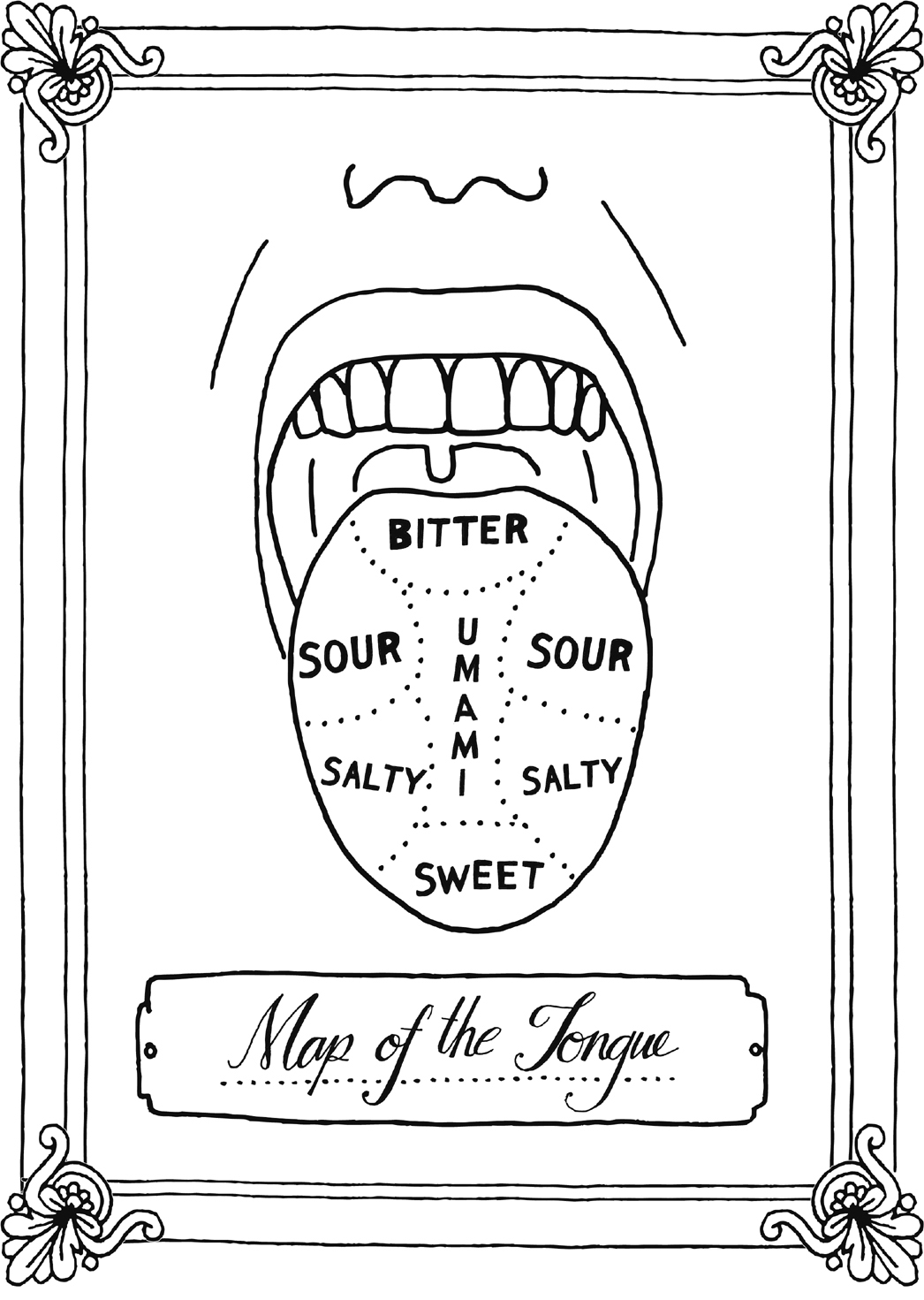

Part of the pleasure and point of eating is realizing the emotional side to food. If eating were just pure science, it wouldn’t be so deeply satisfying. There is so much about food that triggers emotion and memory. Most of it is actually about smell. The tongue itself only detects five things: salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and savory (what the Japanese refer to as

umami

). The rest is interpreted in coordination with our other senses.

In addition, the

ritual

of cooking is so vital to the preservation of culture, to what separates us from animals. The preparation of food is one of the greatest accomplishments of human civilization. (And here you thought my anthropology degree wasn’t useful!)

Just as I see the scientific and the personal elements of cooking at play in professional kitchens, I find there are also two kinds of home cooks: the methodical ones and the improvisational ones, those who follow recipes and those who prefer to just “throw stuff together.”

I meet so many people who tell me they love to cook but who feel they need a recipe to do so. They’re not confident enough to feel as they go, so they follow instructions to the letter.

If these cooks simply paid closer attention to the steps and the order of techniques they use in each recipe, they would start to see patterns, which they could then use with other ingredients and other dishes. If you know how to sauté a piece of chicken, you don’t need a whole new recipe to sauté a piece of fish: you use the exact same technique. The timing might change, but the basic method doesn’t. If you know the foundation behind the science of cooking, you can apply it in endless combinations. Baking is a little more exacting, because of all the subtle chemical reactions required. But a braise is a braise is a braise, whether it’s a slab of pork belly, the tail of a monkfish, or an old rooster. Only cook time and seasoning differentiate them.

An easy technique to master at any cooking level is soup. I love making soup. It’s fast, easy, healthy, and it often tastes better over time. Building a soup is always going to be the same process, no matter what kind of soup you’re making. You start with your flavor foundation:

mirepoix

, which basically means roughly chopped celery, onions, and carrots. It’s the classic French trinity. There can be variations, but usually it’s those three, sometimes with a bunch of herbs added, called a

bouquet garni

. If you want the natural sugars in the vegetables to have more depth of flavor, you sauté (or brown) them first. Otherwise you just sweat them, heating them slowly until they soften. Or just add water and let it boil to infuse the flavor—presto, vegetable stock. Chicken stock is the same thing, but with chicken bones (browned or not).