Talking with My Mouth Full (20 page)

Read Talking with My Mouth Full Online

Authors: Gail Simmons

Sometimes you might add garlic or omit the celery, but it’s usually that easy. You can add other flavorings, like bay leaf or tomato paste, beans or grains, before you add the water or other vegetables. Maybe you want to roast butternut squash in the oven before you add it to your soup. Or you can sauté meat and add it in at this point too. Sometimes you puree the soup, or just puree a few cups of it to add more body and thicken it, or you can leave it all chunky. Once you know how to make a simple stock, you can make any soup, using the same basic method.

The opposite of the recipe-followers are the improvisers. They prefer to experiment, with little guidance. They often make simple mistakes that could have been avoided if they’d only read a recipe. For example, they might not realize that you should deglaze a pan with wine before you add the stock when making a sauce, so the alcohol has time to burn off and you’re left with just its flavor.

Mixing up the order of ingredients and steps in a recipe is a mistake so many of us make. One of the first things they teach you in culinary school is to read a recipe all the way through before starting. Who hasn’t been burned by this? You’re cooking dinner an hour before guests arrive and suddenly you come to an instruction in a recipe like “Refrigerate for twenty-four hours.”

There are always reasons why you cook in a specific order. It’s about building flavor. You put in the carrots before the tomatoes because they take longer to cook. If you put the tomatoes in first, they will burn or turn to mush before the carrots are done. And no one likes mushy, burned tomatoes.

That’s where the term “

mise-en-place

” comes in. It means having everything in its place; gathering all your ingredients in the exact portions required, prepped and ready to go, before you start the actual cooking. If my recipe for Chickpea, Artichoke, and Spinach Stew calls for a large onion, finely sliced, don’t just take out an onion and set it on the counter. Peel it, slice it finely, and set it alongside the rest of the ingredients needed, in the order they’re listed in the recipe. Preparation and organization make cooking so much simpler.

I was one of those kids who would always ask “Why?” when someone said, “Put your coat on.” “Why?” “Because it’s cold out.” “Why?” That’s what you have to do when you’re cooking. Often there are really good answers.

For any recipe to be a success, whether cooked by Daniel Boulud or my mother-in-law, all of its elements need to be harmonious. That’s what I’m looking for when I taste and judge food. When discussing dishes on

Top Chef

, we tend to use words like “acid” or “heat” or “proper seasoning.” This is because we are always trying to create balance for our taste buds, and adding acid cuts fat, which helps achieve this. When eating rich food, you always need a counterpoint. I wouldn’t want to eat a piece of foie gras with butter and cream alone. Or maybe I would.

But certainly it would be monochromatic. That’s why food as fatty as foie gras is usually served with some preparation of tart fruit or paired with sweet wine. It creates contrast to the fat. There’s acid in fruit, and acid equals brightness, balance.

It’s why Americans put ketchup on their fries. Ketchup is basically sugar and tomato paste. And it provides acid to cut the fat and brighten the carbs. Europeans use mayo, which may be rich and fatty, but good quality mayo has brightness, too, as it’s made with lemon and mustard. Hooray for acid!

In Southeast Asian cooking, achieving balance between spicy, sweet, sour, and bitter all in one bite is the constant goal. Acid, in the form of vinegar or citrus, creates a sense of harmony on your palate.

When all of these elements come together–temperature, texture, knife skills, cooking method, and seasoning—it’s like sunshine in your mouth. I’m joking, but really: that perfect balance makes me want to hold hands and sing “Kumbaya.” It just feels so right.

And maybe that’s why I’m the right person to judge food after all. I have a basic understanding of the science of food, but I’m also able to break into song over a little lemon juice.

Wedding Pickles

GIDDILY, WE SPREAD

out our banquet on the living room floor. Welsh rarebit. A frittata with olive oil–cured tuna and shishito peppers. A bottle of ice-cold cava that tastes of apples and citrus. A puffy, eggy German pancake with blueberries. A Scotch egg. A rustic peach tart, fresh and fragrant. A big bag of unpeeled lychees, mild and sweet, just like my mother would buy in Chinatown when I was small, or like the ones I would eat in Israel, under the avocado trees. It’s luxurious not to go outside, not even to get dressed, just to sit in our living room and peel and eat lychee after lychee.

About two years into our relationship, Jeremy and I decided to go to Italy.

My parents were renting a villa in Tuscany for a month and invited us to join them. Who could resist a dreamy Italian vacation? Jer and I planned to stay with them for a few days, then spend a week on our own visiting wineries and Tuscan hill towns.

From the very start, just about everything went wrong.

First of all, my mother had come down with a middle-ear virus. She probably shouldn’t have made the trip in the first place, but my father was insistent. She went even though she felt miserable.

Then the airline lost our luggage. Adding insult to injury, we had made a reservation at an elegant and well-known restaurant for lunch that first day, and now we had to show up in the grubby sweatpants we had worn on the plane.

Then we got to the villa my parents had rented. It was not as advertised. It smelled terrible, the rooms were dark, and it was in the middle of nowhere. The owner was actually there doing renovations on the bottom floor all day, so there was hammering and drilling at all hours, and loud Bollywood ballads blaring late into the night. My father later told me that the owner was drunk when we arrived.

My father is, shall we say, an impulsive traveler. He has been known to make quick decisions before thinking them through. It’s his one flaw—that, and a refusal to admit defeat. But he finally acknowledged he’d made a mistake with the villa, and went to the rental office to insist they find us something better. They offered to move us to a new house, a short distance away.

We set out that evening for the new place, with my parents in one car (along with our family friend Frances) and Jeremy and I following in the second car. It soon became clear that my father had no idea where he was going. He had just been given an address, with vague directions and no map. We took turn after turn, barreled down road after dusty road, driving in circles in the Tuscan countryside. The sun had long since set and it was becoming difficult to see the road. My mother grew so furious with my father that she demanded he pull over, and she got into our car instead.

“Where is he going?!?” she screamed. “He doesn’t even know where we are! This is ridiculous!”

This continued for several hours. Midnight approached. There was not a light, a signpost, or a human to be found. The situation reached a boiling point when we were halted by a herd of cattle in the road and were forced to turn around. My mother insisted we give up and find a hotel back in Cortona.

It was around this time that Jeremy, who had been a true stoic up until this point, leaned over to me and whispered: “I am never traveling with your family again.”

The only place open at that hour in Cortona was a fleabag flophouse on the edge of town that probably rented rooms by the hour. We were afraid to touch anything. We checked in, but we were so riled up that Jeremy and I went down to the bar for a drink. There we found Frances nursing a scotch. We joined her for a few cocktails, until we all had calmed down enough to sleep.

The next morning we decided to give up on the villa idea, and Jeremy and I went off on our own. The rest of our trip was glorious. We ambled through Montepulciano, Siena, and San Gimignano, devouring every wild boar ragu in sight and drinking copious bottles of Chianti and Vino Nobile. Meanwhile, my mother forced my father to take her back to Florence, where she punished him by insisting they stay at the most expensive and luxurious hotel available.

Over the years since, Jeremy and I have traveled a lot together—from Guatemala to London, Spain to Japan, France, Bali, and beyond. But we haven’t taken any more road trips with my parents. I think it’s best for everyone.

Jeremy and I were together for three years before I moved in. Through it all, we did what we came to call “the walk” back and forth between my quirky one-bedroom in the West Village (which my mother lovingly referred to as “tenement chic”) and Jeremy’s apartment in Chelsea. We grew so tired of that damn walk, which we did every other day, carrying bags of clothes.

Finally, it seemed crazy to be carrying two rents, especially after his roommate moved out. New Yorkers tend to move in together more quickly because of the high rent. But we were really ready. Well, at least I was—Jeremy has since confessed that he had a panic attack the night before I moved in. But from the first day, it’s been like a sleepover party every night. I slowly feminized his apartment, and gradually it became ours.

Still, we were together for seven years before he proposed.

About a year into our relationship, I knew this was the person I would be with forever. He had already become my best friend. In other relationships, I’d tried to please men and avoided showing them the less-than-perfect parts of myself. I’ve noticed this pattern in myself and in my friends, in young women in general: by trying to please boys, we tend to give up a bit of ourselves. We start to like their music, to root for their sports teams. We dress the way we think they want us to. We think they’ll like us more if we do everything their way. And so we lose our sense of self.

With Jeremy, I never did that. I never had to. He always liked who I was to begin with. He knew all of me and still stuck around. I think we gave each other a welcome sense of peace in a frantic city where it was often difficult to find any.

“Why aren’t you guys married yet?” my friends would ask. My parents would ask. My parents’ friends would ask. I wanted to get married. I wanted to marry him.

And yet: I loved our life. I wasn’t in a rush. I never felt like I was waiting around. Maybe other people thought I was. But I knew we would always be together. I never thought of it as a decision he had to make—or else.

I had a friend who refused to move in with her boyfriend because she said he would think,

Why buy the cow if you can get the milk for free?

I couldn’t relate to that. I knew one day I would be Jeremy’s wife. I also knew that he was worried about the wedding itself more than the actual marriage. Unlike me, Jeremy loathes being the center of attention. Besides, the thought of all that coordinating and organization petrified him, even though there was no question that I would be the one doing most of the planning. I was working in the event and food world; naturally I was prepared to deal with a wedding. It was the marriage that we were most excited about. As soon as we were married, we both realized it only made things better, in ways we could have never appreciated before.

Now the pressure is on to have children. You always assume it’s the mothers who will be clamoring for grandchildren, but in our case our parents are pretty laid back about it. Instead, it’s friends and even strangers who are asking us about children all the time.

Ironically, many people think we already have kids. Perhaps it’s because

Top Chef

threw a bridal shower challenge for me during Season 5 and then I left, halfway through the season, to get married—compounded by the fact that both Tom and Padma have had children recently. Surely somewhere in there I had children too, right?

I get stopped on the street or asked in press interviews all the time, “How’s your baby?” or “How did you lose the baby weight?” My personal favorite: “You look so great, considering you just had a baby!” Oh, yeah? So how do I look considering I have never had a baby?

Being away from Jeremy is the hardest part of my job. Our friends will call him when I’m out of town to see if he needs someone to play with. But he has his own life, and his own successful music programming and marketing company. He creates music programs for businesses all over the world—restaurants, hotels, events, and retail stores. He actually works with a lot of chefs and restaurants that I know well, so our jobs occasionally overlap.

In a way, being apart several weeks a year has helped us appreciate each other more. But there are times when my constant traveling exasperates him. He’ll call when I’m on set and, just to get me riled up, tell me there’s no food in the house and that he had a frozen hot dog for dinner. Making sure Jeremy is fed is one way I show him how much I care about him. Feeding friends and family is about nurturing and sustaining them. If he tells me he’s been eating Chinese takeout leftovers for days, it signals to me that we need more time together.

When I’m in New York, I still eat out a lot for events and for work, but I try to cook at home at least two or three nights a week. I eat so richly in the rest of my life that at home I try to keep things simple. We don’t eat very much meat. I make big salads and lots of roasted vegetables, inspired by weekend trips to our local farmers’ market: roasted asparagus with poached eggs, quinoa salad with roasted tomatoes, fennel and feta, whole-wheat pizza with roasted cauliflower, chilies, and pecorino. I’ll sauté fish with herbs and lemon or roast chicken with harissa and spices.

In the winter months, I make huge vats of chicken and barley stew from my mother-in-law’s recipe, or kale and white bean soup with kielbasa, or squash or lentil stew.

For breakfast I often bake eggs with mushrooms, potatoes, and chives, or use that whole-wheat pizza dough with a fried egg, cheese, and lots of caramelized onions.

Jeremy definitely has his limits when it comes to how much I am away, and he does occasionally lose patience with the fact that I’m more of a public person now. I’ve been with him far longer than I’ve been on television. For the most part, he thinks it’s fantastic, and often hilarious. He’s genuinely happy about how this adventure has unfolded. And though Jeremy is along for the ride, he can also sit back and watch it with a little more distance. My career has afforded us so many opportunities to travel and eat extraordinary meals around the world. He’s supportive, protective, and in every way my partner. We have a ritual of sharing our life at the end of the day. He gives me a sense of safety and security. My work requires me to do a lot of smiling and being “on,” at events or on camera. With him I can completely let go. And no, we will never have a reality show about our marriage. That’s ours and ours alone.

I also appreciate having a home life that is arm’s length from the industry. It gives me needed perspective. When I become too concerned with what people think of me or what I should be doing next, if I should be working harder or going out more, he’s always there to help me detach from it and refocus my priorities.

Jeremy also helps me keep food in perspective. I’m often asked if I ever get sick of food. The answer is no. But there are times when I’m saturated and can’t think about eating for a while, or when I’m tired of going out and just want to eat something simple. Jeremy reminds me that every meal doesn’t have to matter so much. Sometimes the best thing you can do is have a bowl of soup and go to bed.

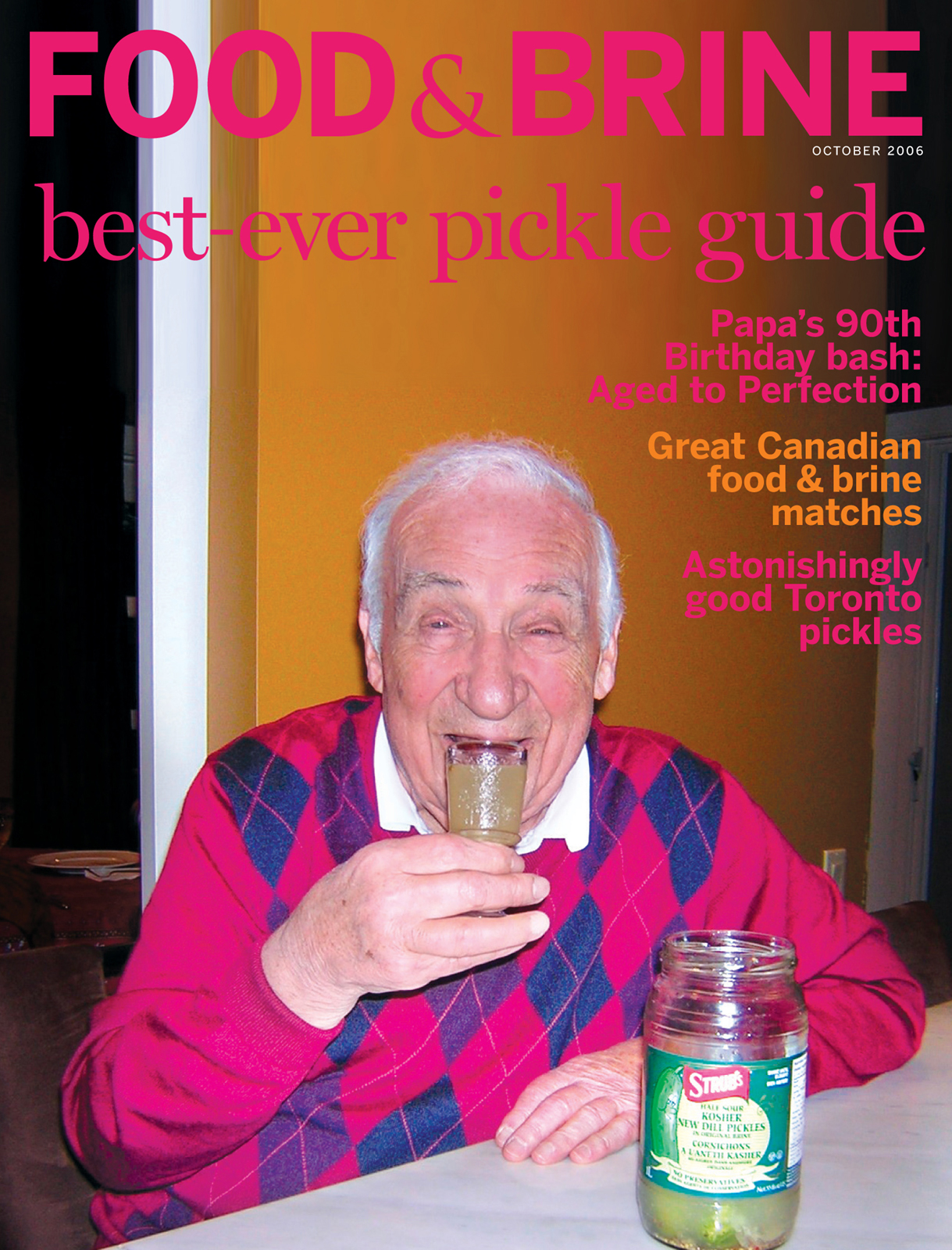

Luckily, we have very similar palates. His fervor for food is just like his grandfather’s, Papa Benjamin, who always is up for a good

nosh

, a good snack. Papa is the only person on Earth who loves pickles even more than I do. Until recently, he drank shots of pickle juice on a regular basis, including on his ninetieth birthday. I believe it is the elixir that has kept him alive for so long. He’s now ninety-five years old, and still sharp as a tack.

A birthday card for Papa’s ninetieth—pickles and all!

(

Trademark Logo © 2011 American Express Publishing Corporation. All Rights Reserved

)

Like Papa, Jeremy’s tastes tend toward the traditional foods of our ancestry. He loves nothing more than kasha (cooked buckwheat grains) and bowtie pasta (also known as farfalle), known in Yiddish as kasha varnishkes. Anything beige and soft gets his vote (slow-cooked helps, too). Brisket. Short ribs. Matzo balls. He’ll take a pastrami sandwich or a potato knish any day of the week, at any and every possible meal. I married an old Jew.

I never liked kasha before I met Jeremy. As a child, I thought it was bland and tasted like cardboard. But I’ve come to love it, because it’s Jeremy’s favorite, especially loaded with caramelized onions and rich mushroom gravy.

Perhaps the most important food-related fact about Jeremy is that he’s the first man who could keep up with my eating. I can’t outeat him and he can’t outeat me. The result: we fight over every last bite. He and I always order the same things. We have the same sensibility.