The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (29 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

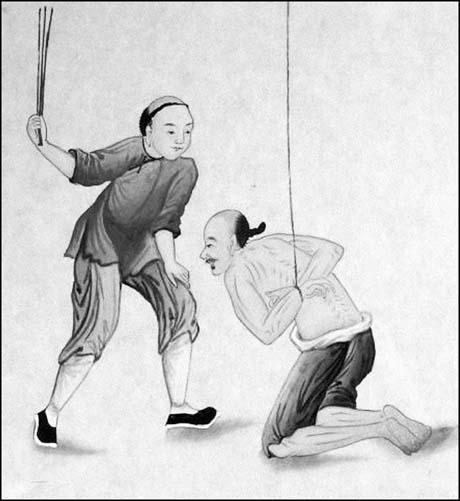

This image shows a Chinese variation on the brodequin. While the victim is stretched out on his stomach (presumably so that he might be flogged or be subject to other torments), the torturers are driving wedges into the slats which hold his legs in order to break the bones of his ankles. It is likely that this was done more as a painful punishment than as a means of extracting a confession.

In those instances where the death penalty was imposed, but where beheading was not called for, as it was in cases of treason, sedition or plotting rebellion, the method of execution could vary greatly. Looking at the nature of these executions one can easily believe that the condemned might have been a lot better off if they had tried to kill the emperor and been hauled off to the block. One method involved stretching the prisoner on a rack-like device before the guards kicked and stamped on him until all his bones were broken; then they beat him to death with heavy clubs. In addition to beheading, being stomped to death and strangulation, there was a particularly grizzly form of execution reserved primarily for those unwise enough to kill their father. In what was known as

Ling Che

, translated alternately as ‘Death by a Thousand Cuts’ and ‘Death by Slicing’, the condemned was, quite literally, carved up like a Christmas turkey. Having centuries to perfect this particularly nasty form of execution, the torture master could make it last as long, or short, a time as the crime and the judge warranted. Once the prisoner had been hauled to a public place and tied down to a table or framework, the executioner appeared with a covered basket containing the tools of his job; a collection of razor-sharp knives, each one marked with the name of a specific body part. Sliding his hand inside the basket, the executioner withdrew a blade at random and proceeded to hack off the designated part. A leg muscle might be cut away, or the ears or, if the condemned was extremely lucky – or the victim’s family had sufficiently bribed the torturer – the ‘heart knife’ might be withdrawn first. A description of such an execution comes to us from an English visitor to China, Sir Henry Norman, and runs as follows:

Grasping hand-fulls from the fleshy parts of the body, such as the thighs and the breasts, [he] slices them off. The joints and the excrescences of the body are next cut away one by one, followed by amputation of the nose, the ears, the toes and the fingers. Then the limbs are cut off piecemeal at the wrists and ankles, the elbows and knees, the shoulders and hips. Finally, the victim is stabbed in the heart and his head cut off.

Far more than just an unimaginably painful death, the

Ling Che

was intended to dishonour the victim and make it impossible for him to rejoin his ancestors in the after-life. It was a horrible punishment in the here and now, with an eternal punishment to follow.

Like the Chinese, their off-shore neighbours, the Japanese, developed a rigid system of punishment wherein honour, and the loss of honour, were as integral to the judicial system as was punishment itself. Also like the Chinese, the Japanese punished minor infractions of the law by whipping the miscreant with a bamboo whip and/or with an elaborate system of fines. When the crime was serious enough to warrant death, however, the highly developed sense of personal honour peculiar to the Japanese played a large part in ridding society of its worst offenders. Among the Japanese, high-ranking men and women were often given the opportunity to commit

hari-kari

(ritual suicide) rather than face the humiliation of public execution. Death was more acceptable than dishonour and death at one’s own hands more acceptable than death at the hands of someone else. For crimes such as treason, where such respectable ends were not likely to be an option, the ‘Death of Twenty-One Cuts’ mirrored almost exactly the Chinese practice of

Ling Che

. Compare this description of the Death of Twenty-One Cuts – given by English traveller Richard Jephson, around 1865, when it was imposed on the captured rebel leader Mowung – with that of the

Ling Che

, above.

Translating roughly as Death by One Thousand Cuts, the Chinese

Ling Che

may well be the most lingering and painful death imaginable. According to tradition, the victim was tied to a table while the executioner appeared with a cloth-covered basket filled with knives, each knife bearing a symbol denoting a particular portion of the body. Reaching under the cloth he would extract a knife at random and slice off the specified body part. Fingers, calf muscles, breasts, thigh muscles, nose, eye lids, it was all in the luck of the draw. Given the right random set of circumstances the torture could go on for hours on end. Inevitably, one knife was marked with the symbol for the heart. When this item appeared the victim’s suffering would end in a matter of seconds. Presumably, there were instances where the condemned man’s family bribed the executioner to find the heart knife immediately.

With superhuman command of self, the unhappy Mowung bore silently the slow and deliberate slicing-off of his cheeks, then of his breasts, the muscles of upper and lower arms, the calves of his legs, etc., etc., care being taken throughout to avoid touching any immediate vital part. Once only he murmured an entreaty that he might be killed outright – a request, of course, unheeded by men who took a savage pleasure in skillfully torturing their victim.

Another equally cruel means of dispatching those convicted of capital crimes was to wrap their bodies in bundles of twigs and set them alight. This crowd-pleasing variation on the old European custom of being burnt at the stake provided the added attraction of watching the poor creature dance around wildly, in excruciating pain, while they were cooked alive.

In Japan, like China, torture was an acceptable means of convincing accused criminals to confess to their crimes and, as was true in the West during the Middle Ages, of making reluctant witnesses provide testimony. Such judicial torture often employed a split-bamboo whip, but unlike the whip used in China to administer punishment for minor infractions of the law, the Japanese whip was constructed so the sharp edges of the bamboo pointed outward, slicing as deep into the flesh of the victim as razor blades. By judicial order, the flogging could last until the victim volunteered to speak, or up to 150 lashes. Beyond that point, further punishment would almost certainly have resulted in death. Another method of loosening tongues and refreshing faulty memories was known as ‘Hugging the Stone’. In this basic but brutal torture, the accused was forced to kneel in a pile of knife-sharp flint fragments while heavy stones were piled in their lap.

He we see a combination of the torture of the pulley and of flogging with ‘the broom’. Depending on where that cord binding his wrists leads, the victim here might be subjected to any one of a number of horrific torments.

Yet another such torture, known as

Yet Gomon

, mirrored almost exactly that used by the Spanish Inquisition. Here, the prisoner’s wrists were bound behind their back and they were lifted into the air by means of a rope, where they were either left to dangle and dislocate their shoulders or dropped, by degrees, and have them jerked out of the sockets in a matter of seconds. This grizzly torture could only be employed in cases of murder, arson, theft, robbery and forgery of a document or an official government seal.

Taking Japan’s long history into account, it seems that the seventeenth century was a period of particular judicial brutality, specifically in relation to the persecution of individuals who adopted Christianity. It seems especially eerie that religious persecution in Japan would so closely mirror, in both intensity and time period, the activities of the Spanish Inquisition. Here, as in Spain, men, women and children were murdered in an orgy of religious intolerance. Some were humiliated by being stripped naked before being thrown from a cliff or tossed into the boiling, natural cauldrons created by Japan’s numerous active volcanoes. Other accused Christians had their limbs roped to four oxen which were then driven in opposite directions, ripping the victim to pieces. In September 1622, fifty Christians were simultaneously burnt alive in the city of Nagasaki. How very much like an inquisitional

auto-de-fe

this gory spectacle must have been. Precisely forty years after this particular mass execution, an equally terrible persecution of Christians took place in the same city. On this second occasion, September 1662, two European chroniclers, Francois Caron, a Frenchman and Joost Schorten, a Dutchman, were on hand to record the events.

They forced the women and more tender maids to go upon their hands and feet … through the streets; that done, they caused them to be ravished … by villains and then throwing them so striped and abused, into great deep tubs full of [poisonous] snakes and adders. Binding the [young men] about with combustible matter … and also their fathers … [they] set fire to them, whereby they underwent inconceivable torments and pains: some they poured hot scalding water continually upon them [and] tortured them in that manner till they died, [some of] which endured two or three days … hundreds of them being stripped naked, and burnt in the foreheads [branded] that they might be known, and driven into the woods and forests, all men being commanded by proclamation, upon fear of death, not to assist them with either meat, drink, clothing or lodging. Once a year they precisely renewed their inquisition, and then every individual person must sign in their church-books, with his blood, that he renounces Christianity.

As it was in both the Orient and Europe, the system of juris prudence and punishment on the subcontinent of India was inextricably linked to both religion and maintenance of the social structure. In India, however, it was religion itself which dictated the shape of the social hierarchy. Hinduism, the official religion of untold millions of Indians, had its origins long before the first Hindu texts, the

Vedas

, were written down sometime around 1000 BC. Integral to this belief system was a rigid, inflexible division of social classes known as

castes

. The original caste system, in descending order, from top to bottom, ran as follows: the

kshatriyas

, the

brahmans

, the

vaishyas

and, at the bottom, the

shudras

(known as untouchables). Although originally the highest social order, by 500 BC the exalted position of the

kshatriyas

had been overtaken by the

brahmans

and, once in power, the

brahmans

did everything they could to retain control of the system. Integral to maintaining their hold on society was controlling all governmental and judicial functions and, through these offices, making it both impossible and illegal for those of lower castes to climb the social ladder. More than forty ethnic sub-groups were declared ‘impure’ and their treatment at the hands of their

brahman

masters, and the mogul emperors who controlled vast swaths of Indian territory, was no better than one would expect for subjugated peoples living in a primitive society.

Conveniently for the

brahmans

, the

Vedas

texts, and the later Laws of Manu, both provided as much support for the repression of the lower classes as the rules of the Spanish Inquisition did for the cruelties inflicted on Jewish

conversos

and Moorish

moriscos

. Like their very un-Christian counterparts in Spain, the

brahmans

insisted that only through ample punishment could the undesirable and criminal classes be ‘saved’ or, in this case, find a better incarnation when reborn into a new life here on earth. As was true of burning heretics and witches, the belief was that the more suffering that accompanied a person’s punishment and/or death, the greater their chances of being ‘purified’. Add to this the vast size and fractured political structure of old India and what emerges is a system of injustice haphazardly applied at the whim of hundreds of local rulers.