The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (31 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

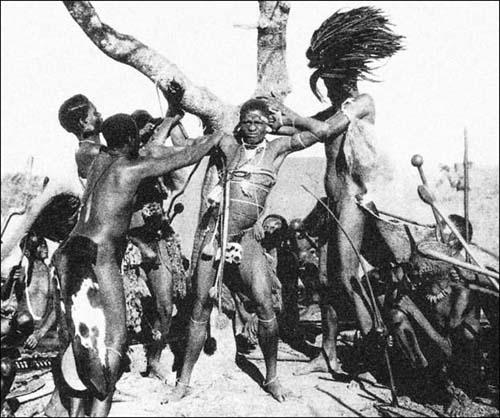

A young African boy submits to an ordeal test by a witch-cleansing cult. Where the causes of illness and misfortune are seen as supernatural, witch-finders remain commonplace.

If African tribal law was almost universally harsh and cruel, it is hardly any wonder that enslaved tribesmen and women expected, and received, no better treatment at the hands of the European slave traders who began exporting them to Spain, Portugal and the Caribbean Islands in the early 1500s. In retrospect it seems almost beyond belief that the so-called civilised people of Europe would trade in captive human beings as though they were cattle.

As late as the mid-seventeenth century, the English attorney-general said: ‘Negroes, being pagans, might justly be held in slavery, even in England itself’. We can assume this was not meant to imply that if these poor creatures converted to the saving grace of Christianity they should immediately be given their freedom. But there was no widespread need for slave labour in Great Britain or Europe. The workforce was required on European-owned ‘New World’ plantations. If their destination alone were not a sufficient death sentence for enslaved Africans, the trip across the ocean – where they were packed like cord-wood in the holds of ships – was unspeakable enough to claim the lives of anywhere from one-fifth to one-third of the average ‘cargo’ of slaves.

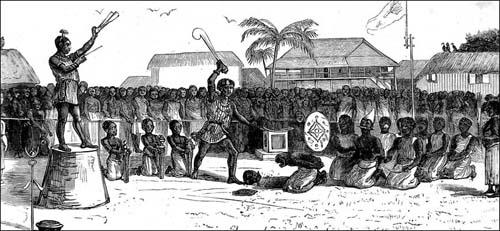

Here we see the systematic and ritualized decapitation of enemy soldiers in the aftermath of some sort of tribal warfare. While it may not adhere to the modern ideas espoused by the Geneva Convention for the treatment of prisoners of war, this is a merciful end in comparison to Greek, Roman and early European treatment of captured enemies.

The sugarcane grown on Caribbean plantations was turned into rum, and as the demand for rum increased back home in England and Europe, the demand for slaves rose commensurately. In 1655, the British captured the island of Jamaica from the French. Three years later they imported a modest 1,400 slaves to work in the fields. By 1670 the total import of human beings had risen to 8,000. By 1720 it had reached 80,000 and by 1775 – the year prior to the American Colonies declaring their independence – it had skyrocketed to 190,000, reaching 250,000 just prior to 1800 and topping out at a colossal total of 314,300 by the time Parliament outlawed the trade in 1824. Note that owning slaves was not outlawed, just importing them from Africa. Even if these hundreds of thousands of people had suffered no tortures worse than being hauled across an ocean to live out their lives in bondage the slave trade would still rank as torture on a scale that would have impressed even Nero or Genghis Khan. Of course, the horrors of slavery did not end with forced emigration, separation of families and hard labour.

When human beings can be purchased as cheaply as 30 English Pounds per head there is little incentive for being nice to the help. Overseers and armed guards watched over the slaves day and night; the slightest infraction of the rules being universally met with severe whippings. Considering the mentality necessary for one man to purchase another, it might not stretch credulity to hypothesise that some of the slave owners and overseers may have taken a sadistic pleasure in flogging another human being until their back resembled ground beef. And it was not only the brutes in the field who tortured the slaves; the landowners and, on occasion even their wives, engaged in such brutality. The following account took place on the Jamaican plantation owned by an English couple by the name of Earnshaw, and the slave in question was a woman named Eleanor Mead.

Her mistress, Mrs Earnshaw, who is described by some as a lady of humanity and delicacy, having taken offence at something which this slave had said or done, in the course of an argument with another slave, ordered her to be stripped naked, prostrated on the ground, and in her own presence caused the male [slave] driver to inflict upon her bared body 58 lashes of the cart whip … One of the persons ordered to hold her prostrate during the punishment was her own daughter, Catherine. When one hip had been sufficiently lacerated, in the opinion of Mrs Earnshaw, she told the [slave] driver to go round and flog the other side.

One might assume that the good Mrs Earnshaw may have had more in mind than punishing Eleanor for arguing with another slave. Possibly Mr Earnshaw liked Eleanor more than was proper, and if his wife had confronted him with her suspicions it would have been Mrs Earnshaw, not the slave woman, on the receiving end of the whip. This may, of course, not be the case at all, but it is a fact that the constant punishment of slaves helped prevent slave couples from marrying. Why? If it is painful to watch fellow prisoners being tortured, how much more painful it must be if the victim is your husband, wife or child? Why would the plantation owners care if their slaves married or not? Because it was cheaper to buy an already grown-up slave freshly imported from Africa than to bear the expense of rearing one from birth until they were old enough to be sent into the fields. How far did such grotesque examples of destroying family life among slaves go? In testimony before the British Parliament, a Protestant minister named Peter Duncan testified as follows:

In the year 1823 I knew of a slave driver having to flog his [own] mother. In the year 1827 I knew of a married Negress having been flogged in the presence of … her husband … Merely because this Negress would not submit to satisfy the lust of her overseer, he had flogged and confined her for several days in the stocks.

As heart-wrenching as Rev. Duncan’s testimony is, it cannot be automatically assumed that all men of the cloth stood bravely in opposition to slavery. In St Anne’s, Jamaica, in 1829, the Rev. G.W. Bridges was charged with maltreating a mixed-race slave woman. It seems the good reverend had invited a guest for dinner and ordered this particular woman to prepare a turkey dinner for the occasion. For whatever reason the guest did not show up and Bridges took out his anger on the cook. After tearing off all of her clothes he bound her hands and hung her from a conveniently placed hook in the ceiling. Then he whipped her with a bamboo rod until – according to testimony presented at his trial – ‘she was a mass of lacerated flesh and gore’.

While it has always been considered unforgivable for one person to whip another’s horse or dog, it seems as though it was perfectly acceptable to whip another man’s slaves. If the beating was severe enough to cause permanent damage, or even kill the victim, providing an equivalent, replacement slave would almost always compensate for any hard feelings.

Not surprisingly, whippings were not the limit of punishment forced on the victims of slavery. Offences large and small could be punished by branding, or they might be branded for exactly the same reason a cow is branded – to establish ownership. For slaves prone to running away, there were always chains and shackles secured to the bunkhouse walls and ball-and-chains that could be worn in the fields. There were also iron collars with foot-long spikes projecting in three or four directions, nearly identical to those we found being used in ancient China. Of course, if a slave simply refused to accept bondage and continued to run away, his or her owner was completely within their rights to hack off one of their legs. A late eighteenth-century traveller through the Jamaican town of Paramaribo stated that during his stay in the town he saw: ‘No less than nine Negroes [who] had each [had] a leg cut off for running away’.

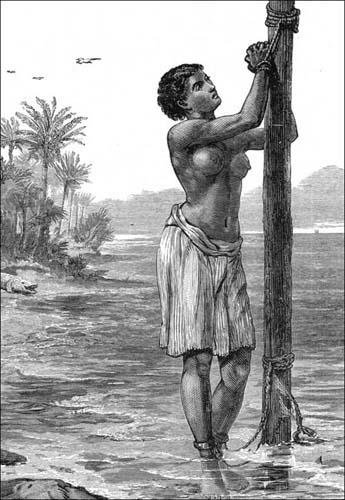

A slave is bound to a lashing post. Here she will await flogging or branding or whatever other torments her captors may devise, though she is also under threat from the rising tide and from the crocodiles pictured on the left-hand side of the image.

It should come as no surprise that now and again the slaves rose in revolt against their masters. Such an event occurred on the island of Santo Domingo in 1791 and the ensuing carnage was beyond belief; each side doing their level best to massacre the other in the most abominable ways they could think of. When one of the rebel leaders was captured he was hauled through the streets of town, standing in the back of a cart while on his way to execution. He was not tied there, his feet had been nailed to the floorboards of the wagon. In an eerie echo of the medieval European practice of being broken on the wheel, the man’s limbs and ribs were smashed to pieces before he was thrown, still alive and screaming, onto a roaring fire.

Equally barbaric tortures were used by Europeans on the slaves worked to death in the African colonies. In Dutch-held Surinam, a slave convicted of a capital offence was first hooked through the ribcage with a wrought-iron hook, the opposite end of which was attached to a chain. The poor wretch was then hoisted up on a gallows, or a convenient tree, and left to dangle until he died of exposure or suffocation brought about by a ripped diaphragm. As late as 1900 slaves in the Belgian Congo were ‘questioned’ by being hoisted into the air by ropes tied around their armpits.

Once suspended, heavy weights were then tied to their feet and a saw-horse-like structure was set between their legs. If they refused to talk, or cooperate, or if the exercise was purely disciplinary in nature, they were dropped onto the horse so that their genitals were crushed and their pelvis shattered.

The hatred engendered by the long night-mare of slavery did not magically end when slavery was abolished. Tortures very much like those recounted above were still being inflicted on the people of Haiti – by their own leaders – well into the second half of the twentieth century.

Most of us comfort ourselves with the belief that torture no longer exists and therefore has no influence on the modern world. Nothing could be further from the truth for two reasons. First, events of the past are relevant in the modern world because if we forget them, or deny them – as some Spanish still deny that the Inquisition was as horrible as it really was and some revisionist historians refute the reality of Adolf Hitler’s death camps – then we are doomed to repeat the cruelties of the past until the end of time. Secondly, and more ominously, the use of torture is alive and well. It exists in Zimbabwe, in Iran, in Afghanistan, Cuba, in Saudi Arabia and dozens of other nations and places around the globe. If there is a moral to be had in all of this it is that no matter what justification is used for torture, its practice and use is rooted in only one thing – the maintenance of power of one group over another. Even in instances such as the Spanish Inquisition and the great witch hunts – where God and the protection of the faith were employed as moral justification for torture and corporal punishment – the underlying factor was inevitably the wielding of personal and political power over a perceived – and almost certainly imaginary – enemy. So long as any society or nation is ruled by fearful leaders, torture will always be an issue. So long as general populations delight in the blood-sport of ‘harsh justice’, shamefully avert their eyes from things they would rather pretend did not exist or tacitly accept whatever their government tells them, torture, brutality and man’s inhumanity to man will follow as surely as thunder follows lightning.