The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (27 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

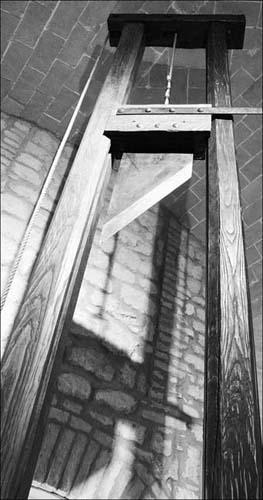

It took the revolution two and a half years to pass a bill decreeing that all executions in the Republic would take place on the machine rapidly becoming known as Madame Guillotine (as well as ‘The People’s Avenger’, ‘The National Razor’, ‘Saint Guillotine’ and ‘The Patriotic Shortener’) and almost immediately the ungainly device began popping up all over France. The first victim of the first guillotine was Nicholas-Jacques Pelletier, whose execution for theft had been delayed specifically so he could try out the Revolution’s new toy. To make the most of the occasion – and the least of the fountains of blood that inevitably followed the fall of the blade – the machine had been painted red and Pelletier was dressed in matching hues. Almost instantly variations on the guillotine sprang up everywhere. Some had multiple blades and others, like multi-seated privies, were designed to accommodate more than one victim at once. Miniature replicas of the death machine appeared as children’s toys capable of decapitating anti-revolutionary sparrows. Diminutive guillotines adorned the dinner tables of revolutionaries and, when made of glass and porcelain, were filled with perfumes. Robespierre, himself, draped one in blue buntings and made it an object of worship in a newly invented ‘religion’ dedicated to the ‘goddess of reason’.

Science quickly now discovered a new and surprising fact (confirmed by modern neurophysiology): a head decapitated by a swift slash of an axe or guillotine knows that it is a beheaded head whilst it rolls along the ground or into the basket. Consciousness survives long enough for such a perception. After the execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette on 21 January 1793, the ‘machine’ (called only thus until this date) became known as ‘la louisette’ or ‘le louison’; only after 1800 did the term ‘la guillotine’ become established.

Those less imbued with the true spirit of the revolution, however, began to ask disturbing questions: Did it really kill as quickly as its inventor claimed? On more than one occasion a victim’s head was seen to roll its eyes and try to speak as it tumbled across the scaffold amid a fountain of blood. When Charlotte Corday – sentenced to death for having murdered revolutionary pamphleteer Jean-Paul Marat – was beheaded, the executioner picked up her head and slapped her face. Before life flickered out, Corday looked at her killer and scowled. One wonders what Maximilien Robespierre’s reaction was when his own turn came to meet the National Razor. Given its reputation and association with the Reign of Terror, it is hardly surprising that the Guillotine never gained wide acceptance outside of France.

While ‘Madame Guillotine’ was tidying up resistance to the revolution at the rate of thousands a week, London was doing away with its own miscreants at the paltry rate of one hanging every fortnight, but the array of crimes which lead to the king’s gallows was still growing. By 1820, people were being hanged for such horrific offences as stealing a single piece of wood, defacing Waterloo Bridge and impersonating one of the old-age pensioners at Chelsea Barracks. Sickened by the inability of England to reform her own judicial code, subjects of the Crown took matters into their own hands – at least when called up for jury duty. When a man was charged with having stolen a £10 banknote the jury valued the piece of paper at 39

s

– a misdemeanour. When another man was charged with stealing a sheep, the jury only found him guilty of stealing the wool – also a misdemeanour. Similarly, a horse thief was found guilty of the petty crime of stealing horse hair.

Still, as handy as England’s judges were with the gallows, progress was being made in other areas. Since torture as punishment had been made illegal, when a person was convicted of a crime that called for branding, the condemned was asked to hold a slice of ham while the bailiff pressed a cold branding iron against the slab of meat. Undoubtedly the symbolic act was followed by a stern lecture, but it was a lot less painful than the alternative. Like branding, flogging slowly went the way of the dinosaur. The last known case of judicially imposed flogging in Great Britain took place in Scotland in 1817 and in 1820 the whipping of women was abolished. Two years later the flogging of men was also outlawed, but the practice would continue as a standard disciplinary measure in the Royal Navy until 1881.

These restraints show a technological refinement and humanitarian development from their medieval ancestors. We see a lead cuff (top) for locking about a prisoner’s wrists and leading them from place to place. Wrist shackles (centre) have built in locks and rounded edges, making them marginally more comfortable to wear than earlier examples. And the ankle fetters (bottom) exhibit similar properties. These devices developed as a result of the move toward incarceration and imprisonment in favour of private or public torture for judicial punishment.

In a truly forward-looking move, Warwickshire courts began imposing one-day sentences on youthful offenders in 1820. As part of this imaginative early-release program, the youth had to promise to go home at the end of the day and their parents swore to guarantee the child’s future behaviour. It was a far cry from one generation earlier when a child caught stealing a loaf of bread would have been hanged. When these one-day sentences were first imposed they were officially unrecognised, but their unquestioned effectiveness was carefully followed by the best legal minds in London.

These heartening statistics should not be taken to indicate that centuries of abuse ended with a few enlightened judges or the single stroke of a pen. In 1823, Grey Bennet testified before the House of Lords that he was aware of at least 6,959 cases of whippings that had taken place inside England’s prisons over the previous seven years. By and large, however, British prisoners were being released from their shackles and chains and put to work cleaning up the squalid conditions in which they lived. Some prisoners spent shifts on treadmills which ran ventilating fans that helped freshen the fetid air and remove collected moisture from jail cells. Similar treadmills were used to pump sewage out of prisons and pump in clean water and still others were used to operate flour mills. It may not have taught the inmates a useful trade but it was a vast improvement over being chained to the wall of a damp dungeon.

In 1829, London became the last major city in Europe to receive a police force. Under the guiding hand of Sir Robert Peel (who had established a similar force in Ireland in 1812), the London Metropolitan Police – commonly known as ‘Peelers’ or ‘Bobbies’, after their founder, or as ‘Coppers’ after the copper buttons on their uniforms – began tackling the crime problem at its source. The earlier crime could be detected, and the sooner criminals realised that there was little chance of escaping the long arm of justice, the sooner the honest people of London – and eventually the citizens of every town and city throughout Great Britain, Europe and the rest of the world – could sleep in relative ease.

Despite the best efforts of social reformers everywhere, the twin problems of dealing with crime and meting out punishment have never been adequately solved. No matter how harsh, or how lenient, judicial systems are, criminals still haunt every corner of the planet. How we, today, deal with them is still being examined by our court and legislative systems and will continue to be debated for the foreseeable future. How non-European countries and societies have sought to deal with these interconnected problems, at various times in the past, will be examined in the next chapter.

B

ased on what we have seen so far, it might easily be construed that torture was somehow limited to the Western World. This would be an incorrect assumption. Torture and cruelty are not limited to any specific culture, geographic area or time period. Wherever weak, fearful people struggle to retain their grip on power, there is an almost unlimited capacity to inflict pain and suffering in the name of the greater good. Consequently, this chapter will deal with a few select cultures, scattered across the planet and through the centuries, where torture has been accepted as an integral part of the social structure. With these broad parameters in mind, it seems only logical to begin with that most ancient of human cultures, China.

Among Western nations China is perceived as a place brimming with strange and exotic methods of inflicting an unimaginable array of tortures. Considering what we have already seen of Western civilisations it would be erroneous to credit the Chinese with a greater sense of cruelty than the rest of the world. It is fair to say, however, that the Chinese attitude toward torture remained unchanged for a longer period of time than it did among Western nations. Until the early years of the twentieth century, the Chinese system of judicial punishment was based on the Tang Code of law, instituted some time around 200 BC. This continuity gave the Chinese slightly more than two millennia to perfect their approach to inflicting pain, and perfect it they certainly did.

Old China, like most early civilisations, had a strictly delineated class system and punishment was meted out according to a person’s social status. Slaves who committed bodily assault on a free man or woman were executed, while a free man who killed a slave – be it his own or someone else’s – could receive no greater punishment than a single year of imprisonment. If a nobleman killed a slave, or even a free commoner, they were subject to no punishment at all. For the bulk of society – that is to say the entirety of the free population below noble rank – there was a sliding scale of punishments determined not only by the severity and nature of the crime, but also by the social status of the accused. For those of a higher rank who assaulted, robbed or murdered someone of a lower rank, the punishment was considerably less than it was for someone of a lower social rank who committed the same offence against a person of higher rank. If this seems like a shockingly medieval approach for a civilisation as enlightened as China, we must take into account that Chinese society was based on a rigid sense of order and propriety. Crime in any form disrupted that order and it was essential that social balance be restored lest the fabric of society unravel as chaos ensued. The Tang Code was every bit as concerned with guaranteeing the perpetuation of the proper order of things as it was with punishing wrongdoers.

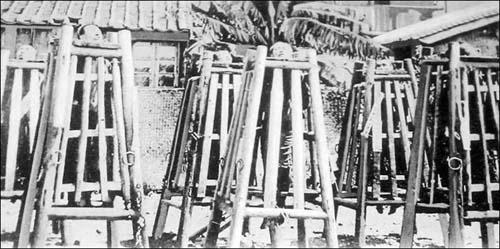

Twentieth-century Chinese postcard depicting prolonged execution by exposure through confinement in bamboo cages. Whether the weight of these unfortunate men is being supported entirely by their necks or whether their ankles have also been locked within restraints is unclear from the image.

To make this complicated system workable, the Code was divided into two sections; the first dealt with basic principals of civil and criminal law, and the second with portioning out the proper penalties for every conceivable type of crime – taking into consideration the various circumstances under which it may have been committed as well as the social class of both perpetrator and victim. Because the Chinese are a philosophical people, the Code also contained lengthy justifications as to why one punishment was more appropriate for a given offence than another. If this seems impossibly complex, at least it ensured that justice was portioned out according to law rather than the whim of the presiding judge, as was so often the case in Western Europe. To make this system work as efficiently and impartially as possible, the guilt of the accused had to be established beyond any shadow of doubt, and the only way this could be accomplished was through a confession. In all fairness to what is about to come, it should be mentioned that those who confessed to the crime prior to their trial – thus saving the court a lot of time and money – were subject to receiving a much lighter sentence than those refusing to confess even in the light of overwhelming evidence of guilt. Today we would call this plea-bargaining. For those who obstinately refused to confess, there were a variety of ways to make them reconsider.