The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (26 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

This example of a public pillory shows how popular this sort of spectacle could be.

With the Fieldings leading the way toward reform, John Howard took up General Oglethorpe’s fallen banner in 1755 and again insisted that England could not possibly call itself a progressive nation until it reformed its prison system. Like Oglethorpe, Howard decried the complete wastage of human life imposed by a system that shackled men and women to a wall when they could be taught a trade, or given productive work to do. What Howard included in his report, that Oglethorpe had not, were numerical statistics. Of 4,375 inmates polled, half of them were found to be in prison because they were unable to pay their debts. Most hardened criminals – at least those who had not been hanged at Tyburn – had been transported to the colonies, flogged, pilloried, or branded. Howard concluded his report by stating that most of the people who were incarcerated were either debtors; were awaiting trial; had been imprisoned for misdemeanours or were simply too poor to buy their way out of jail. He also cited an earlier report which stated that more than 5,000 people died in British jails every year from starvation. It took John Howard nearly twenty years to get the government to listen, but in 1774 he finally convinced Parliament to investigate conditions in Britain’s prisons. As they had done when General Oglethorpe carried out his study more than forty-five years earlier, the new report was quietly shelved and ignored, despite the fact that more and more international voices were calling for the world to rethink the manner in which it dealt with society’s misfits.

In 1764, Cesare Beccaria, an Italian lawyer from Milan, published a treatise entitled

Crimes and Punishments.

In his paper, Beccaria said the best way to fight crime was through prevention rather than punishment; that everyone was entitled to a speedy trial and that the use of torture, either to extract a confession or as a means of punishment, was futile. The work must have caught someone’s attention; it was translated into twenty-two languages and went through six Italian editions in only eighteen months. Five years later, an English magistrate expressed similar sentiments when he wrote: ‘it is scarcely to be credited that by the laws of England, there are above 160 different offences which subject the guilty parties to the death penalty’. Compare this to the thirty-two hanging offences in force only seventy years earlier, and the fact that the number of capital crimes would continue to rise until, by the end of the century, they would top-out at a staggering 220. Predictably, however, nobody seemed willing to take action on reforming the system; not even when King George III personally established a fifteen-member cabinet to review each and every death sentence passed in England – excepting those where the conviction had been for murder. Each case may have been carefully reviewed, but the numbers of hangings continued to increase as the list of capital offences grew. The best anyone seemed able to do was devise more efficient ways of hanging people. In 1760 a new ‘drop’ method was proposed. Rather than simply hauling the condemned into the air and allowing them to kick and thrash until they slowly strangled, the drop was supposed to ensure a speedy death by breaking the victim’s neck. The first man given an opportunity to try out this advanced technology was the Earl Ferrers, but the trap failed to open properly, the Earl was left to choke to death and business continued as usual at Tyburn’s hanging tree.

This was the inevitable and unavoidable fate for those poor souls in Salem Massachusetts condemned as being guilty of witchcraft.

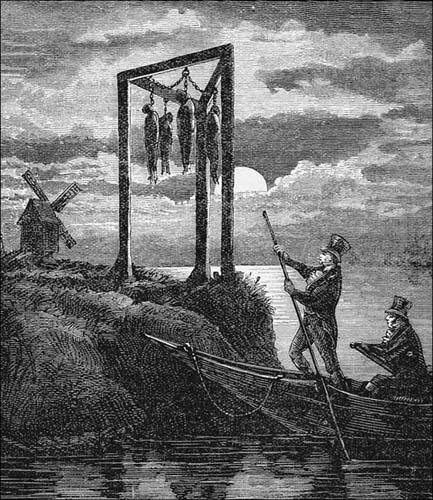

Finally, in 1783, it was decided that public executions did more to excite a ghoulish populace than it did to eliminate crime. Henceforth, hangings would no longer be public affairs and on 7 November 1783 the last man was hanged at that cherished institution, the Tyburn Tree. While reformers may have taken some small comfort at this de-glorification of execution, even as respected a personage as Dr Samuel Johnson – compiler of the first English language dictionary and conversationalist extraordinaire – thought it signalled the end of civilisation. ‘The age is running mad for innovations’, he cried, ‘even Tyburn is not safe. Executions are intended to draw spectators. If they don’t, they don’t answer their purpose. The public is gratified by a procession; the criminal is supported by it.’ Eight years later, in 1791, gibbeting was outlawed as was the public flogging of females – women could still be whipped as punishment for some crimes, but the sentence could not be carried out in public.

For all its flaws and failures, the eighteenth century had witnessed some laudable progress in the way criminals, and suspected criminals, were dealt with. New rules of procedure made hearsay evidence less acceptable, and torture to elicit a confession had been outlawed. Adding to this was the fact that defendants were prohibited from offering any evidence in court; if no statement from a defendant was admissible, then a confession extracted by torture had no value. By 1827 a law had been passed whereby a plea of ‘not guilty’ was automatically entered any time a suspect refused to plead either guilty or not guilty – it was a distinct improvement over ‘pressing’ a plea out of a suspect. Similarly, in the newly established United States of America, the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution guaranteed that no-one could give self-incriminating evidence.

Although uncounted thousands of Englishmen and women were convicted of capital crimes during the 1700s, less than one out of three were actually hanged. Deportation to the American Colonies (or, after America’s Declaration of Independence in 1776, to Australia) was considered a more humane alternative to execution. Prisoners, however, did not always see it this way and on more than one occasion convicts insisted they would rather swing than be transported. There was certainly justification for their fears. Conditions onboard prison ships were comparable to the worst dungeons of the Middle Ages. Between 1750 and 1755 alone, the bodies of more than 2,000 dead prisoners were dumped into New York harbour, thousands more floated in other American harbours and who knows how many human carcasses had been tossed overboard at sea. The value placed on a deported criminal’s life is made clear by the fact that the British government offered anyone willing to help establish colonies in Australia a grant of 4,000 acres of land, forty cows and forty convict-slaves. Captain Arthur Phillip, first governor of New South Wales, Australia, wrote to the Crown asking: ‘if the convicts commit either murder or sodomy, may I sell them to the natives for meat?’ We do not know what answer he received.

Despite the perils of transportation and the less than progressive attitude of their guardians, the overall success of deportation brought about its own sort of reform of the English penal system. When the British public learned that thousands of prisoners were helping to build roads and improve the physical infrastructure of newly established towns in America and Australia, they began insisting that prisoners in Britain be given similar productive tasks to perform.

Outside Great Britain, similar changes in the treatment of law breakers were also coming about. Ecclesiastical courts were slowly losing their power to impose physical punishments on individuals whose crimes were more of the spirit than of the flesh. Even the more traditionally structured nations were slowly stripping away the power of local noblemen and war-lords, forcing them to hand over suspected criminals to government-controlled courts who followed rules set down by a central judiciary. Integral to this process of reform was the slow abolition of torture. In most cases, as had been true in Great Britain, torture as a means of extracting a confession was stricken from the books before it was abolished as a form of punishment. In 1721, Elector Frederick I of Prussia decreed that torture could only be used after he, personally, had reviewed the case in question. In 1754, Frederick II – known as Frederick the Great – outlawed torture altogether. In 1734, Sweden became the first country to outlaw the use of torture in any form, for any purpose. Between 1738 and 1789 the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies did away with torture as did Austria between 1769 and 1776. Thanks largely to the work of Milanese lawyer, Cesare Beccaria, Italy banned torture in 1786 and the Netherlands followed suit between 1787 and 1794.

In 1801, Czar Alexander I of Russia was made aware of a case wherein a prisoner had confessed to a crime under torture but had later been proven innocent. On 27 September, the Czar decreed that his government must, henceforth:

ensure with all strictness throughout the whole Empire that nowhere in any shape or form … should anyone dare permit or perform any torture, under pain of inevitable and severe punishment … that accused persons should personally declare before the Court that they had not been subjected to any unjust interrogation … that finally the very name of torture, bringing shame and reproach on mankind, should be forever erased from the public memory.

Spain only followed suit in 1812, the same year it belatedly abolished the Holy Office of the Inquisition and the horrors that had accompanied it since 1484.

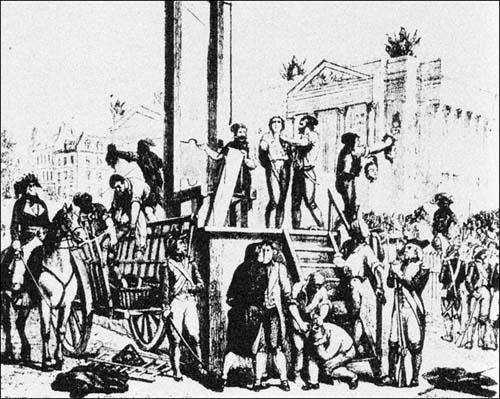

Like Spain, France seemed more reluctant than most of her continental neighbours to adopt penal and corporal reforms. As late as the mid-eighteenth century, a man convicted of the attempted assassination of King Louis XV was condemned to having the offending hand lopped off before molten lead and boiling oil were poured on the bleeding stump; and this was only the prelude to the real sentence. Horses were tied to each of the man’s limbs and then whipped off in all directions in an attempt to dismember the felon. As his joints proved stronger than the horses, the executioner stepped in and loosened the man’s arm and leg joints with a knife. As late as 1791, victims were still being boiled in oil and only because Voltaire refused to stop writing about the inequities of the French judicial system were the rack and flogging abandoned in 1789. The year 1789 was significant to the history of French punishment in at least one other way as well. On 14 July of that year an angry mob stormed Paris’s Bastille prison, signalling the downfall of the monarchy. As brutal and bloodthirsty as the revolution and the ensuing Reign of Terror were, the Revolutionary Assembly did manage to outlaw the use of torture in criminal investigations. Despite the tens of thousands of innocent people who were sentenced to death in the name of the Revolution, those found guilty of less egregiously treasonous offences than suspicion of being a closet monarchist or addressing their neighbour as ‘Monsieur’ rather than the more politically correct ‘Citizen’, were simply condemned to being dressed down by the court with the following words: ‘Your country has found you guilty of an infamous action: the law and the tribunal strips you of the quality of French citizenry.’ Unlike the British, who sent their outcasts to the American Colonies or Australia, the French did not seem to care where the condemned went so long as they left France. For those found guilty of truly anti-revolutionary offences there was a far more famous, and infamous, end in store, but this particular institution of the Reign of Terror had its beginnings long before the fall of the Bastille and the rise of ‘La Revolution’.

It was the French physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotine who first promoted a law that required that all executions (even those of commoners and plebeians) be carried out by means of a ‘machine that beheads painlessly’. An easy death – so to speak – was no longer to be the prerogative of nobles. After a series of experiments on cadavers taken from a public hospital, the first of these machines was put up in the Place de greve in Paris on 4 April 1792, and the first execution (in this case of a common highwayman) took place on 25 April. Soon this invention was to become the hallmark of the years 1792–94. It is worth noting here that the entire motive behind its invention and use was to do away with the more torturous aspects of public execution. Death was intended to be swift and painless … or at least that was the idea.

On a balmy Paris day in May 1738 a heavily pregnant woman was so shocked by the sight of a man having his limbs shattered on the wheel that she had to be carried home after going into premature labour. Both mother and son survived their ordeal with no apparent side effects. She and her husband named the boy Joseph: the family name was Guillotine. Forty-eight years later, in 1785, Joseph Guillotine began experimenting with mechanical methods of separating a man from his head – other nations had used such devices before, as we saw with the Halifax Gibbet, but since none of the previous inventors had been French, beheading machines had never seemed acceptable to the French. By October 1789, the Revolutionary Assembly had taken power and Joseph Guillotine managed to arrange an audience to explain the principal of his machine. The supposedly instantaneous death by decapitation seemed to be in line with the new French policy of abolishing torture. Maximilien Robespierre – the Machiavellian head of the Committee of Public Safety who would send uncounted thousands to their death in the name of liberty – openly wept because he insisted that the thought of harming another human being was abhorrent to him, and it should be obvious to anyone that Guillotine’s beheading machine was entirely painless. More importantly for the egalitarian-minded Revolutionary Assembly, citizen Guillotine’s machine would be used on all malefactors regardless of their social class. An equal death for all French citizens.