The Conflict

Authors: Elisabeth Badinter

To Robert

Table of Contents

THE SILENT REVOLUTION

Over the last three decades, almost without our noticing, there has been a revolution in our idea of motherhood. This revolution was silent, prompting no outcry or debate, even though its goal was momentous: to put motherhood squarely back at the heart of women's lives.

At the end of the 1970s, once women had gained access to birth control, they turned their energies to achieving essential rights, of freedom and equality with men, which they hoped to reconcile with motherhood. Being a mother was no longer the beginning and end of being a woman. Women now could choose from a range of possibilities, choices their mothers never had. They could give priority to personal ambitions, remaining single or as part of a couple, without children,

or else they could satisfy their desire for motherhood whether or not they were also working.

or else they could satisfy their desire for motherhood whether or not they were also working.

This new freedom, however, has proved to be a source of contradiction. On the one hand, it has significantly altered the status of motherhood by implicating mothers in a raft of added responsibilities for the children they have chosen to have. On the other hand, by putting an end to age-old notions of biological destiny and necessity, it has brought the concept of personal fulfillment to the fore. Women should have a child, or two children or more, if having children enriches their emotional experience and corresponds to their choices in life. If not, they should abstain. The individualism and hedonism that are hallmarks of our culture have become the primary motivations for having children, but also sometimes the reason not to. For a majority of women it remains difficult to reconcile increasingly burdensome maternal responsibilities with personal fulfillment.

Thirty years ago, we still hoped we could square the circle by sharing the workplace and home equitably with men. We thought we were well on our way to this goal but the 1980s and 1990s marked the beginning of a profound threefold crisis that brought an end (perhaps temporarily) to our earlier ambitions: an economic crisis, coinciding with an identity crisis, prompted a crisis of equality between the sexes, halting all progress. This is evident in the wage salary gap, which has prevailed ever since.

The economic slump of the early 1990s sent a good many

women back to the home, particularly those with the least education or training who were the most economically vulnerable. In France parents were offered government assistance to stay at home for three years and look after their young children. After all, it was felt, raising a child is as much a job as any other, and often more rewardingâexcept that it was considered worth half the minimum wage. Massive unemployment affected women far more than it did men, and had the added effect of restoring motherhood to center stage, valued as more reliable and gratifying than a poorly paid job that might disappear overnight. In addition, an unemployed father is always considered more detrimental to the family than an unemployed mother, and at the same time, child psychologists kept coming up with new responsibilities for parents that seemed to fall to the mother alone.

women back to the home, particularly those with the least education or training who were the most economically vulnerable. In France parents were offered government assistance to stay at home for three years and look after their young children. After all, it was felt, raising a child is as much a job as any other, and often more rewardingâexcept that it was considered worth half the minimum wage. Massive unemployment affected women far more than it did men, and had the added effect of restoring motherhood to center stage, valued as more reliable and gratifying than a poorly paid job that might disappear overnight. In addition, an unemployed father is always considered more detrimental to the family than an unemployed mother, and at the same time, child psychologists kept coming up with new responsibilities for parents that seemed to fall to the mother alone.

The economic crisis therefore put paid to our hope that men would change. Their resistance to equality and sharing the work at home remained as strong as ever and the promising beginnings we thought we had seen went no further. Today, just like twenty years ago, women take on three-quarters of the domestic work, and since unequal division of labor in the home is the primary cause of the wage gap, inequality is thriving. But the economic crisis is not the only reason for stalled progress toward equality. Perhaps unprecedented in human history and far harder to resolve, another crisis compounded the economic damage: one of

identity.

identity.

Until recently, the world of men and the world of women were sharply differentiated. The complementary nature of their respective roles and responsibilities fostered a sense of identity specific to each. But once men and women were able to take on the same roles and carry out the same responsibilitiesâin both public and private spheresâwhat was left of their essential differences? While motherhood remained the sole privilege of women, where is the exclusive sphere preferred for men? Are they to be defined only negatively, as people who cannot bear children?

All this has provoked profound existential disorientation for men. The question is made all the more complex by the possibility of removing men from the process of conception altogether, and by the necessity, perhaps, of essentially redefining motherhood. Is the mother the one who provides the egg, the one who carries the baby, or the one who raises the child? And what does all this mean for the essential differences between being a father and being a mother?

In the face of so much upheaval and uncertainty, we are sorely tempted to put our faith back in good old Mother Nature and denounce the ambitions of an earlier generation as deviant. This temptation has been reinforced by the emergence of a movement dressed in the guise of a modern, moral cause that worships all things natural. This ideology, which essentially advocates a return to a traditional model, has had an overwhelming influence on women's future and their choices. Just as Jean-Jacques Rousseau succeeded in doing,

troops of this movement intend to persuade women to return to nature, which means reverting to fundamental values of which maternal instincts are a cornerstone. But, unlike in the eighteenth century, women now have three options: embracing motherhood, rejecting it, or negotiating some middle ground, depending on whether they privilege their personal pursuit or a maternal role. The more intenseâor even exclusiveâthat role is, the more likely it is to conflict with other demands, and the more difficult the negotiation between the woman and the mother become.

troops of this movement intend to persuade women to return to nature, which means reverting to fundamental values of which maternal instincts are a cornerstone. But, unlike in the eighteenth century, women now have three options: embracing motherhood, rejecting it, or negotiating some middle ground, depending on whether they privilege their personal pursuit or a maternal role. The more intenseâor even exclusiveâthat role is, the more likely it is to conflict with other demands, and the more difficult the negotiation between the woman and the mother become.

In addition to the women who feel fulfilled by having children and the increasing number who, voluntarily or not, turn their back on it, are all those who, aware of the demanding ideologies of motherhood, attempt to reconcile their desires as women with their responsibilities as mothers. The result of these competing interests has been to shatter any notion of women forming a united front. This is another reason to reconsider how we define women's identity.

This evolution is apparent in all developed countries, but there are marked differences depending on history and culture. Women from a range of backgroundsâEnglish, American, Scandinavian, Mediterranean, but also German and Japaneseâall engage the same issues and reach their own conclusions. Interestingly, French women seem to form a group of their own. It is not that they are oblivious to the dilemma confronted by others, but their concept of motherhood derives, as we'll see, from an older notion, one that took

shape more than four centuries ago.

1

It might well be thanks to this that they have the highest rate of pregnancy in Europe. Which makes one wonder whether the eternal appeal to the maternal instinct, and the behavior it presupposes, are in fact motherhood's worst enemies.

shape more than four centuries ago.

1

It might well be thanks to this that they have the highest rate of pregnancy in Europe. Which makes one wonder whether the eternal appeal to the maternal instinct, and the behavior it presupposes, are in fact motherhood's worst enemies.

THE STATE OF PLAY

THE AMBIVALENCE OF MOTHERHOOD

Before the 1970s, children were the natural consequence of marriage. Most women able to give birth did so virtually as a matter of course. The imperative to reproduce was a combination of instinct, religious duty, and a sense of responsibility to the survival of the species. It went without saying that any normal woman wanted to have children, a self-evident fact so rarely contested that, even very recently, one could read in a magazine a pronouncement stating, “The desire for children is universal. The urge comes from the depths of our reptilian brain, from the reason we are here in the first place: to continue the species.”

1

Yet now that a large majority of women use contraception, ambivalence toward motherhood is more evident and those vital urges sent forth from our reptilian brains seem somewhat diminished. The desire for children is

in fact neither constant nor universal. Some women want them, some no longer do, others never wanted them at all. Now that we have a choice, there is a variety of options and it is really no longer possible to talk about instincts and universal longings.

1

Yet now that a large majority of women use contraception, ambivalence toward motherhood is more evident and those vital urges sent forth from our reptilian brains seem somewhat diminished. The desire for children is

in fact neither constant nor universal. Some women want them, some no longer do, others never wanted them at all. Now that we have a choice, there is a variety of options and it is really no longer possible to talk about instincts and universal longings.

Choosing to Be a Mother

Every choice entails motives and consequences. Bringing a child into the world is a long-term commitment that takes precedence over all others. It is the biggest decision most human beings will make in their lives. Common sense would suggest that people consider the decision thoroughly and ask themselves serious questions about their capacity for altruism and how much pleasure they might derive from raising a child. But does this always happen?

The French publication

Philosophie Magazine

recently published a highly instructive survey. When asked “Why have a child?” the men and women questioned responded that:

2

Philosophie Magazine

recently published a highly instructive survey. When asked “Why have a child?” the men and women questioned responded that:

2

| A child improves daily life and makes it happier | 60% |

| A child means continuing the family, handing down its values and history | 47% |

| A child gives love and affection, and company in one's old age | 33% |

| A child means giving someone the gift of life | 26% |

| A child makes a couple's relationship more intense and stable | 22% |

| A child helps you become an adult and take responsibility | 22% |

| A child allows you to leave something of yourself behind when you die | 20% |

| You can help your child achieve things you could not do yourself | 15% |

| Having a child is a new experience, introducing something new to your life | 15% |

| To please your partner | 9% |

| Having a child is a religious or ethical choice | 3% |

| Other reasons | 4% |

| For no particular reason, by accident | 6% |

| Total | |

| Have children, would like to or would have liked to | 91% |

| Do not have children and do not want to | 9% |

Philosophie Magazine

rightly points out that although 48 percent of the answers are associated with love and 69 percent with duty, 73 percent involve pleasure. Hedonism ranks first among the motives, with no mention of self-sacrifice.

rightly points out that although 48 percent of the answers are associated with love and 69 percent with duty, 73 percent involve pleasure. Hedonism ranks first among the motives, with no mention of self-sacrifice.

The truth is, reasoning has little role in the decision to have children, probably less than in the decision not to do so. Given the large part the subconscious plays in both choices, we have to admit that most parents do not know why they have a childâtheir motives are infinitely more obscure and ill-defined than those suggested in the survey. Hence the temptation to put it down to overriding instinct. In fact, the decision derives more from emotional and societal factors than from any rational assessment of advantages

and disadvantages. There is frequent acknowledgment of the emotional aspect, but far less attention paid to the important pressures coming from family, friends, and society. A woman (and to a lesser extent a man) or a couple without children is always seen as an anomaly, up for interrogation. How strange not to have children like everyone else! Childless people are always expected to explain themselves, although it would never occur to anyone to ask a woman why she became a mother (and to insist on getting good reasons), even if she were the most immature and irresponsible of parents. But people who choose not to have children are spared nothingânot the sighing from their parents (whom they deny the joy of grandchildren), not the incomprehension of their friends (who want everyone to do the same thing they've done), and not the disapproval of society and the state, both of which are by definition pro-birth and have countless little ways of punishing you for not doing your duty. It therefore requires a strong will and tremendous character to make light of a set of pressures that amount to stigma.

and disadvantages. There is frequent acknowledgment of the emotional aspect, but far less attention paid to the important pressures coming from family, friends, and society. A woman (and to a lesser extent a man) or a couple without children is always seen as an anomaly, up for interrogation. How strange not to have children like everyone else! Childless people are always expected to explain themselves, although it would never occur to anyone to ask a woman why she became a mother (and to insist on getting good reasons), even if she were the most immature and irresponsible of parents. But people who choose not to have children are spared nothingânot the sighing from their parents (whom they deny the joy of grandchildren), not the incomprehension of their friends (who want everyone to do the same thing they've done), and not the disapproval of society and the state, both of which are by definition pro-birth and have countless little ways of punishing you for not doing your duty. It therefore requires a strong will and tremendous character to make light of a set of pressures that amount to stigma.

The Hedonist Dilemma, or Maternity versus Freedom

Individualism and the quest for personal fulfillment lead future mothers to ask questions they would not have considered in the past. Now that motherhood is no longer the only source of affirmation for a woman, the desire to have children might conflict with other desires. A woman with

an interesting job who hopes to build a careerâalthough such women are a minorityâcannot fail to consider such questions as whether a child would harm her professionally. How would she manage to combine a demanding job with raising a child? What effect would that undertaking have on her relationship with her partner? How would she need to reorganize her home life? Will she still be able to enjoy her advantages and, more important, how much of her freedom would she have to relinquish?

3

This final question affects many women, not only those with professional ambitions.

an interesting job who hopes to build a careerâalthough such women are a minorityâcannot fail to consider such questions as whether a child would harm her professionally. How would she manage to combine a demanding job with raising a child? What effect would that undertaking have on her relationship with her partner? How would she need to reorganize her home life? Will she still be able to enjoy her advantages and, more important, how much of her freedom would she have to relinquish?

3

This final question affects many women, not only those with professional ambitions.

In a civilization that puts the self first, motherhood is a challenge, even a contradiction. Desires that are considered legitimate for a childless woman no longer are once she becomes a mother. Self-interest gives way to selflessness. “I want everything” becomes “I must do everything for my child.” And the moment a woman chooses to bring a child into the world for her own satisfaction, notions of giving are replaced by debt. The gift of life is transformed into an infinite debt toward a child that neither God nor nature insists you have, and one who is bound to remind you at some point that he or she never asked to be born.

The more freedom we have to make decisions, the more duties and responsibilities we have. While children might be an undeniable source of fulfillment for some, they might turn out to be a burden for others. It depends on how much women invest in motherhood and on their capacity for altruism. Yet before they reach their decision, very few

women (or couples) calculate clearly the pleasures and hardships, the benefits and sacrifices. Quite the opposite: the realities of motherhood are more often obscured by a halo of illusions. The future mother tends to fantasize about love and happiness and overlooks the other aspects of child rearing: the exhaustion, frustration, loneliness, and even depression, with its attendant sense of guilt.

women (or couples) calculate clearly the pleasures and hardships, the benefits and sacrifices. Quite the opposite: the realities of motherhood are more often obscured by a halo of illusions. The future mother tends to fantasize about love and happiness and overlooks the other aspects of child rearing: the exhaustion, frustration, loneliness, and even depression, with its attendant sense of guilt.

Recent French accounts of motherhood

4

indicate just how ill-prepared many women are for this shattering upheaval. No one warned me how hard this would be, they say. “Having a child is something anyone can do, but few future parents know the truth, it's the end of your life”

5

âmeaning, the end of my freedom and the pleasures it afforded. A baby's first months are particularly trying: “It can't be possible to be needed this much or for me to be fulfilled by this dependence, this remorseless, inescapable anxiety.”

6

And: “He nursed and nursed some more, doggedly intent on the job, chained to this programed activity as I was to the TV ⦠. I woke up, I went back to sleep, it was day, it was night, no one ever warned me it would be so boringâor I'd never have believed them.”

7

4

indicate just how ill-prepared many women are for this shattering upheaval. No one warned me how hard this would be, they say. “Having a child is something anyone can do, but few future parents know the truth, it's the end of your life”

5

âmeaning, the end of my freedom and the pleasures it afforded. A baby's first months are particularly trying: “It can't be possible to be needed this much or for me to be fulfilled by this dependence, this remorseless, inescapable anxiety.”

6

And: “He nursed and nursed some more, doggedly intent on the job, chained to this programed activity as I was to the TV ⦠. I woke up, I went back to sleep, it was day, it was night, no one ever warned me it would be so boringâor I'd never have believed them.”

7

For one of these writers, happiness ultimately replaces the boredom, but for the others emptiness remains the overwhelming experience and all they can think of is getting back to the outside world.

Â

Â

Motherhood is still the great unknown. For some, it brings incomparable happiness and enriches their identity. Others manage as best they can to reconcile contradictory demands. Yet others cannot cope and find the experience a failure yet they will never admit it. In our society, to admit that you are not cut out to be a mother, that it gives you little satisfaction, would brand you as a reckless monster. Yet this is the reality. Think how many children, at every level of society, are unloved and neglected. In the 1970s,

Chicago Sun-Times

columnist Ann Landers asked her readers whether they would still choose parenthood knowing what they knew. Of the ten thousand responses she received, an amazing 70 percent answered in the negative.

8

On balance, those people felt that the sacrifices were disproportionately large for the satisfaction they received. While the experiment was not scientificâdisappointed parents were the most motivated to respondâit did give voice to an experience that is generally unrecognized.

9

Chicago Sun-Times

columnist Ann Landers asked her readers whether they would still choose parenthood knowing what they knew. Of the ten thousand responses she received, an amazing 70 percent answered in the negative.

8

On balance, those people felt that the sacrifices were disproportionately large for the satisfaction they received. While the experiment was not scientificâdisappointed parents were the most motivated to respondâit did give voice to an experience that is generally unrecognized.

9

Motherhood and the virtues it presupposes are not a given, no more today than they were when being a mother was a woman's destiny. Contrary to what we might have believed, making the choice to be a parent is no guarantee of being a better one. For one thing, our belief in having chosen from a position of freedom might be illusory; for another, this assumed freedom burdens women with greater responsibilities at a time when individualism and a “passion for the self”

10

have never been stronger.

10

have never been stronger.

We know from Emile Durkheim's work that marriage comes at a cost to women and is to the advantage of men. A century after Durkheim's investigations, subtle differences have inflected this finding, but the domestic injustice

11

persists: married life has always come at a social and cultural cost to women, not only in terms of the unequal division of household work and child rearing, but also in its detrimental effect on their career and salary prospects. Today, it is not so much marriage itself that takes its toll on women (marriage no longer being a necessity), but sharing a household and especially the birth of a child. Sharing a household, which is now widespread, has not brought an end to domestic inequality, even if surveys show that it is more favorable to women than marriage, at least in the early days of the relationship. It is the arrival of a child that dramatically increases the amount of time women spend on domestic chores,

12

while the men, in their role as fathers, invest more time in their jobs. According to François de Singly, “the scope of household choresâand the justification for themâhas less to do with men's demands than with children's genuine or assumed needs. When children leave home we have quasi-experimental confirmation that the toll of conjugal life derives in large part from the toll of having children.”

13

11

persists: married life has always come at a social and cultural cost to women, not only in terms of the unequal division of household work and child rearing, but also in its detrimental effect on their career and salary prospects. Today, it is not so much marriage itself that takes its toll on women (marriage no longer being a necessity), but sharing a household and especially the birth of a child. Sharing a household, which is now widespread, has not brought an end to domestic inequality, even if surveys show that it is more favorable to women than marriage, at least in the early days of the relationship. It is the arrival of a child that dramatically increases the amount of time women spend on domestic chores,

12

while the men, in their role as fathers, invest more time in their jobs. According to François de Singly, “the scope of household choresâand the justification for themâhas less to do with men's demands than with children's genuine or assumed needs. When children leave home we have quasi-experimental confirmation that the toll of conjugal life derives in large part from the toll of having children.”

13

It is true that the more qualifications women have, the

less domestic work they do and the more they invest in their professional livesânot that this means their partner does more in the home.

14

A woman's academic capital, de Singly observes, is used mainly to pay for outside help, something that less qualified working women cannot afford. The difference inspired this sociologist to comment: “The revolution in lifestyle has more closely aligned qualified women with men, while shifting them further from their less qualified sisters.”

15

While professional women tend to devote themselves to their work, sometimes to the point of renouncing motherhood altogether, others make the opposite choice, particularly when work is hard to come by and poorly paid. Social inequality, compounded by gender inequalities, has a huge bearing on whether women choose to have children or not.

less domestic work they do and the more they invest in their professional livesânot that this means their partner does more in the home.

14

A woman's academic capital, de Singly observes, is used mainly to pay for outside help, something that less qualified working women cannot afford. The difference inspired this sociologist to comment: “The revolution in lifestyle has more closely aligned qualified women with men, while shifting them further from their less qualified sisters.”

15

While professional women tend to devote themselves to their work, sometimes to the point of renouncing motherhood altogether, others make the opposite choice, particularly when work is hard to come by and poorly paid. Social inequality, compounded by gender inequalities, has a huge bearing on whether women choose to have children or not.

Since women gained control of their fertility, four phenomena have become apparent in developed countries: a decline in the per capita birthrate; a rise in the average age of first-time mothers; an increase in the number of women in the job market; and a diversification of women's lifestyles with the emergence, in many countries, of couples and single women without children.

Fewer Children, No Children

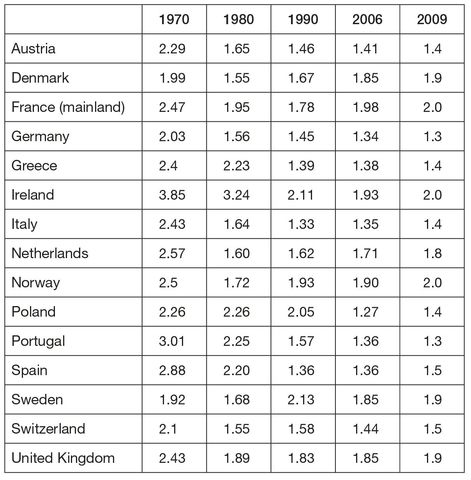

Industrial countries barely achieve population replacement (and some are nowhere near it), despite increasingly generous family policies in many of them. In Europe, the decline in childbirth is steep, as demonstrated by figures for the average number of children per family from 1970 to 2009:

16

16

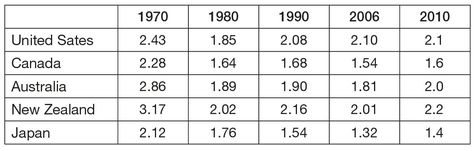

Even though there are significant differences between northern and southern Europe, the tendency to decline is universal, as it is in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, although in some places there has been a slight rise in birthrates in recent years:

While demographers do not entirely agree on the efficacy of family policies (Swedish women have benefited in this area for more than twenty years but have fewer children than American and Irish women, who do not enjoy the same advantages), these remain the primary lever in trying to reverse the trend. Every country is now asking the same questions: How to convince couples to have more children? And how to help them? Family policies tend to be more traditional, meaning that they prioritize couples, or more progressive, favoring women (apart from Scandinavian countries, few put pressure on men to improve the division of household chores), but whatever help is given to women to reconcile their family and professional lives (generous maternity leave, good child care for under-threes, flexible working hours), the

majority of European women are still not disposed to reach that key figure of 2.1 children.

majority of European women are still not disposed to reach that key figure of 2.1 children.

Interestingly, France comes close, as does Ireland, but for different reasons: the church's influence in Ireland is incontestable, while in France contraception and abortion are widely available (since 1967

17

and 1975, respectively). Immigration does not account for the higher birthrate in France; although the birthrate of immigrants is initially higher, the second generation tends to fall in line with the rest of French women.

18

The statistics are, in fact, difficult to explain. As in other countries, partnerships

19

are no more stable, and many French mothers continue to work after having a second child. Additionally, pro-birth policies are less generous or far-reaching than in Scandinavian countries.

17

and 1975, respectively). Immigration does not account for the higher birthrate in France; although the birthrate of immigrants is initially higher, the second generation tends to fall in line with the rest of French women.

18

The statistics are, in fact, difficult to explain. As in other countries, partnerships

19

are no more stable, and many French mothers continue to work after having a second child. Additionally, pro-birth policies are less generous or far-reaching than in Scandinavian countries.

On the other hand, few French women choose not to have children at all. This phenomenon seems barely to have touched France. One in ten will not have children (by choice or not), a proportion that has hardly changed since 1940

20

and is still “markedly lower than figures from many European countries: 17% in England, Wales and the Netherlands, 20% in Austria and 29% in West Germany, for women born in 1965.”

21

In the United States and Australia, some 19.7 percent of women do not have children.

22

20

and is still “markedly lower than figures from many European countries: 17% in England, Wales and the Netherlands, 20% in Austria and 29% in West Germany, for women born in 1965.”

21

In the United States and Australia, some 19.7 percent of women do not have children.

22

Nevertheless, like most other women, the French seem in no hurry to have children, as if childbearing is no longer their highest priority. First, they work to ensure their independence by studying for ever-longer periods of time to gain

access to rewarding jobs (during times of financial crisis, this process takes longer and is less reliable). Then they seek out a partner who is desirable as the father of their children. Finally, many couples decide first to enjoy their life together, unencumbered by responsibilities. The “maternal drive”

23

kicks in toward the age of thirty, and more insistently between thirty-five and forty. The biological clock pushes women to make a choice; it sometimes seems that the age constraint and a fear of renouncing all possibility of motherhood are the decisive factors, rather than an irresistible desire to have a child. The child is incorporated as an added extra in a busy life in which the women already have all their bases covered.

access to rewarding jobs (during times of financial crisis, this process takes longer and is less reliable). Then they seek out a partner who is desirable as the father of their children. Finally, many couples decide first to enjoy their life together, unencumbered by responsibilities. The “maternal drive”

23

kicks in toward the age of thirty, and more insistently between thirty-five and forty. The biological clock pushes women to make a choice; it sometimes seems that the age constraint and a fear of renouncing all possibility of motherhood are the decisive factors, rather than an irresistible desire to have a child. The child is incorporated as an added extra in a busy life in which the women already have all their bases covered.

This is not the only or the dominant approach to motherhoodâthe hallmark of our times is the variety of choice. Some women long to devote themselves to a large family; some want children as well as a rewarding job; others do not want children at all; and some childless women might pursue having a child at any cost. There are undoubtedly many different ways of thinking about motherhood.

24

24

Diversity in Women's Choices

To understand these factors more clearly, researchers in English-speaking countriesâthe first to confront the phenomenon of childless womenâdeveloped a system of classification. Catherine Hakim, a senior research fellow at the London Center for Policy Studies, identified three distinct

categories: home-centered, adaptive, and work-centered, and outlined the characteristics of each group.

25

categories: home-centered, adaptive, and work-centered, and outlined the characteristics of each group.

25

| HOME-CENTERED | ADAPTIVE | WORK-CENTERED |

|---|---|---|

| 20% of women | 60% of women | 20% of women |

| varies 10%â30% | varies 40%â80% | varies 10%â30% |

| Family life and children are the main priorities throughout life | This group is the most diverse and includes women who want to combine work and family, plus the undecided and those who have not planned careers | Childless women are concentrated here. Main priority in life is employment or equivalent activities in the public arena: politics, sports, art, etc. |

| Prefer not to work | Want to work, but not totally committed to work career | Committed to work or equivalent activities |

| Qualifications obtained for intellectual dowry | Qualifications obtained with the intention of working | Large investment in qualifications/training for employment or other activities |

| Responsive to social and family policy | Very responsive to all policies | Responsive to employment policies |

While some branches of the social sciences suggest that women comprise a homogenous group that strives to combine

work and family life, Hakim emphasized the differing extents to which women are involved in their work. Unlike most feminist rhetoric, which argues for women's common interests, she examines the “full diversity of women's employment and life histories.” This “heterogeneity of women's preferences and priorities creates conflicting interests between groups of women,”

26

which, Hakim argued, proves highly advantageous to men, whose interests, by comparison, are homogenous. In her view, this is the main reason that the equality model has failed. Compared to women, men have presented a more unified front, particularly during the “prime age” of twenty-five to fifty: “Men chase money, power, and status with greater determination and persistence” than women, Hakim wrote.

27

Even though a degree of male diversity has appeared in recent decades, it remains insignificant compared to that of women. Men who choose to invest their time in domestic chores represent a very small minority. As Hakim pointed out, in both the public and private spheres, there might always have been women ready to challenge men for power, but few men who have responded to the challenge by taking over their children's upbringing. Even in Scandinavian countries, she observed, with their generous paternity leave, fathers are not inclined to devote themselves to the family although they are guaranteed the equivalent of their full salary.

28

work and family life, Hakim emphasized the differing extents to which women are involved in their work. Unlike most feminist rhetoric, which argues for women's common interests, she examines the “full diversity of women's employment and life histories.” This “heterogeneity of women's preferences and priorities creates conflicting interests between groups of women,”

26

which, Hakim argued, proves highly advantageous to men, whose interests, by comparison, are homogenous. In her view, this is the main reason that the equality model has failed. Compared to women, men have presented a more unified front, particularly during the “prime age” of twenty-five to fifty: “Men chase money, power, and status with greater determination and persistence” than women, Hakim wrote.

27

Even though a degree of male diversity has appeared in recent decades, it remains insignificant compared to that of women. Men who choose to invest their time in domestic chores represent a very small minority. As Hakim pointed out, in both the public and private spheres, there might always have been women ready to challenge men for power, but few men who have responded to the challenge by taking over their children's upbringing. Even in Scandinavian countries, she observed, with their generous paternity leave, fathers are not inclined to devote themselves to the family although they are guaranteed the equivalent of their full salary.

28

In 2008 in the United States, Neil Gilbert, professor of social welfare at the University of California at Berkeley,

suggested another form of classification: he distinguishes among four categories of women that correlate to how many children they have.

29

In 2002, 29 percent of American women between the ages of forty and forty-four had three or more children, 35.5 percent had two, 17.5 percent had one, and 18 percent had none. Looking at these percentages, Gilbert described four types

30

of lifestyles for women based on the importance given to work and to the family. At one end are mothers of large families (three or more children), “traditional”

31

women. They find their identity and fulfillment in bringing up their families and running their households. A high proportion of them have experience of the world of work but choose to distance themselves from itâperhaps intending to rejoin the job market laterâto stay at home as full-time mothers. They believe that their children's day-to-day care and upbringing are the most important things in their lives, and they derive a profound sense of achievement from child rearing. Although they opt for a traditional division of labor in the home, this does not necessarily represent a return to the patriarchal model. Many of these women see themselves as their spouse's partner in the full sense of the term. This category of women has significantly decreased since the 1970s, Gilbert pointed out, declining from 59 percent in 1976 to 29 percent in 2002.

suggested another form of classification: he distinguishes among four categories of women that correlate to how many children they have.

29

In 2002, 29 percent of American women between the ages of forty and forty-four had three or more children, 35.5 percent had two, 17.5 percent had one, and 18 percent had none. Looking at these percentages, Gilbert described four types

30

of lifestyles for women based on the importance given to work and to the family. At one end are mothers of large families (three or more children), “traditional”

31

women. They find their identity and fulfillment in bringing up their families and running their households. A high proportion of them have experience of the world of work but choose to distance themselves from itâperhaps intending to rejoin the job market laterâto stay at home as full-time mothers. They believe that their children's day-to-day care and upbringing are the most important things in their lives, and they derive a profound sense of achievement from child rearing. Although they opt for a traditional division of labor in the home, this does not necessarily represent a return to the patriarchal model. Many of these women see themselves as their spouse's partner in the full sense of the term. This category of women has significantly decreased since the 1970s, Gilbert pointed out, declining from 59 percent in 1976 to 29 percent in 2002.

At the other end of the continuum are the women Gilbert called “postmodern.” These are childless women, whose numbers nearly doubled in the same period, from 10 percent

to 18 percent. They are highly individualistic and dedicate themselves to their careers. These women, most of whom have an abundance of academic qualifications, find their fulfillment in professional success whether in business, politics, or the professions. A survey carried out in England in 2004 found similar results to Gilbert's: out of five hundred women without children, 28 percent said they were independent, happy with their lot, adventurous, and had confidence in their ability to control the main facets of their life. “As happy alone or in the company of friends as with a partner, these women have ambitions that are not shaped by the prospects of marriage and family life.”

32

Fewer than half the women interviewed agreed that having a family and a welcoming home would give them a true sense of achievement.

to 18 percent. They are highly individualistic and dedicate themselves to their careers. These women, most of whom have an abundance of academic qualifications, find their fulfillment in professional success whether in business, politics, or the professions. A survey carried out in England in 2004 found similar results to Gilbert's: out of five hundred women without children, 28 percent said they were independent, happy with their lot, adventurous, and had confidence in their ability to control the main facets of their life. “As happy alone or in the company of friends as with a partner, these women have ambitions that are not shaped by the prospects of marriage and family life.”

32

Fewer than half the women interviewed agreed that having a family and a welcoming home would give them a true sense of achievement.

In the middle of Gilbert's continuum are “neo-traditional” women with two children, and “modern” women,

33

who want to earn a living but are not so committed to their careers as to renounce motherhood. These categories constitute the majority, and they are often seen as representative of all women who divide their time between work and family. But in trying to balance these different demands, “modern” women tend to tip the scales in favor of their careers whereas “neo-traditionalists” give higher priority to family life. These two groups are distinguished from the “traditional” and the “postmodern” only by a matter of degree. Mothers of two children are usually employed part-time and invest more of themselves physically and psychologically in their home

lives than their jobs. (Since 1976, the number of mothers who have two children at home and are over the age of forty has increased by 75 percent. In 2002 they represented 35 percent of women in this age group.) On the other hand, a “modern” mother, one with professional commitments and one child, spends more time and energy on her work than a “neo-traditional.” (The proportion of this category has climbed by 90 percent since 1976, and now constitutes 17.5 percent of its age group.)

33

who want to earn a living but are not so committed to their careers as to renounce motherhood. These categories constitute the majority, and they are often seen as representative of all women who divide their time between work and family. But in trying to balance these different demands, “modern” women tend to tip the scales in favor of their careers whereas “neo-traditionalists” give higher priority to family life. These two groups are distinguished from the “traditional” and the “postmodern” only by a matter of degree. Mothers of two children are usually employed part-time and invest more of themselves physically and psychologically in their home

lives than their jobs. (Since 1976, the number of mothers who have two children at home and are over the age of forty has increased by 75 percent. In 2002 they represented 35 percent of women in this age group.) On the other hand, a “modern” mother, one with professional commitments and one child, spends more time and energy on her work than a “neo-traditional.” (The proportion of this category has climbed by 90 percent since 1976, and now constitutes 17.5 percent of its age group.)

Although these two sets of classification apply specifically to the United States, they serve to illuminate the diversity of choices regarding motherhood and lifestyles that are now available to all women.

But these choices are not set in stone. They evolve in line with the economic climate and social and family policies. Equally important are changing ideologies of motherhood and the pressures exerted on women to conform to fashionable models of a good mother. We know that the view of the ideal mother changed radically in France in the eighteenth century, from a remote, offhand approach to child raising to one that was active, exclusive, and dedicated, and this model has persisted for nearly two centuries. Feminist ideology and contraception might have subsequently opened up the parameters, but there are now opposing efforts to push women toward a more constrictive model of the good mother. The consequences, however, might end up being very different from the intention.

Other books

The Hellfire Conspiracy by Will Thomas

Cowboy Take Me Away by Soraya Lane

The Penny Ferry - Rick Boyer by Rick Boyer

Diners, Drive-Ins, and Death: A Comfort Food Mystery by Christine Wenger

Holly Hearts Hollywood by Conrad, Kenley

Dovey Coe by Frances O'Roark Dowell

Bride of Death (Marla Mason) by Pratt, T.A.

Beyond the Hell Cliffs by Case C. Capehart

Soul Seeker by Keith McCarthy