The Dictionary of Homophobia (116 page)

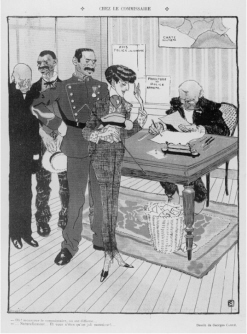

Drawing by Georges Carré.

A young man arrested by the morality squad: “But, Captain!

I am defamed … naturally…. And you are such a handsome man!…”

In countries where homosexuality’s legal status is either vague or negative, police continue to harass their gay and lesbian populations. Police in Romania, under the repressive communist government of Nicolae Ceaucescu, were well known for their arrest, beating, and torture of homosexuals. The Serbian police barely defended Belgrade’s participants in the country’s first Gay Pride on June 30, 2001, when hooligans assailed them. Homophobic police behavior is also common, and often brutal, in Turkey and Albania, in several countries of

Latin America

(Brazil, Venezuela, Peru, Costa Rica), in most Muslim countries, in many countries of

Africa

, and in

India

and

China

. Almost everywhere, transvestites and effeminate gays seem to be particularly vulnerable targets of police aggression.

—Pierre Albertini

Amnesty International.

Breaking the Silence: Human Rights Violations Based on Sexual Orientation

. London: Amnesty, 1997.

Buhrke, Robin A.

Matter of Justice: Lesbian and Gay Men in Law Enforcement

. New York/London: Routledge, 1996.

Carlier, François.

Etudes de pathologie sociale: Les deux prostitutions

. Paris: E. Dentu, 1887.

Gury, Christian,

L’Honneur perdu d’un politicien homosexuel en 1876

. Paris: Kimé, 1999.

———.

L’Honneur perdu d’un capitaine homosexuel en 1880

. Paris: Kimé, 1999.

Leinen, Stephen.

Gay Cops

. New Brunswick: Rutgers Univ. Press, 1993.

Lever, Maurice.

Les Bûchers de Sodome

. Paris: Fayard, 1985.

Peniston, William A. “Love and Death in Gay Paris: Homosexuality and Criminality in the 1870s.” In

Homosexuality in Modern France

. Edited by Jeffrey Merrick and Bryant T. Ragan Jr. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996.

Rey, Michel. “Police et sodomie à Paris au XVIIIe siècle,”

Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine

. Paris (1982).

Seel, Pierre.

Moi, Pierre Seel, déporté, homosexuel

. Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1994.

Sibalis, Michael David. “The Regulation of Male Homosexuality in Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, 1789-1815.” In

Homosexuality in Modern France

. Edited by Jeffrey Merrick and Bryant T. Ragan Jr. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996.

Tamagne, Florence.

Histoire de l’homosexualité en Europe, Berlin, Londres, Paris, 1919–

1939. Paris: Le Seuil, 2000. [Published in the US as

A History of Homosexuality in Europe: Berlin, London, Paris, 1919–1939

. New York: Algora, 2004.]

Tsang, Daniel C. “US Government Surveillance.” In

Gay Histories & Cultures

. Edited by George E. Haggerty. New York/London: Garland, 2000.

Weeks, Jeffrey.

Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain, from the Nineteenth Century to the Present Time

. London: Quartet Books. 1977.

—Armed Forces; Criminal; Criminalization; Deportation; Gulag; Hoover, J. Edgar; McCarthy, Joseph; Mirguet, Paul; Pétain, Philippe; Prison; Stonewall; Violence.

POLITICS (France)

The subject of homophobia in politics is immense. It is also a difficult one to define, given the necessity of talking about it in terms of institutionalized homophobia, political parties, and elected officials, including politicians who are either suspected of being homosexual or who publicly declare their homosexuality. Regardless, while recent French political history has been subject to an obvious and sometimes violent homophobia—particularly around the debates over the

PaCS

(Pacte civil de solidarité; Civil solidarity pact) civil union proposal and the issue of gay

parenting

—questions remain unanswered about its appearance in earlier times.

First of all, let us note that France’s political milieu, from the French Revolution of 1789 to more recent times, has been dominated by men, even after the introduction of laws on gender parity. It is men who developed the country’s political culture and its rites and rituals (long before political parties allowed women as members) and monopolized national representation and government. History has shown that single-gender social groups such as the

army, prisons

, or even convents, were conducive to the development of homosexual relationships. Can the same be said for the political milieu, which has remained almost exclusively masculine for so long? The proof remains elusive but we can assume, without fear of error, that some legislators and members of government were homosexual. And it is not unthinkable that among the few women who entered French politics since 1944, some may have been lesbians. However, it remains that until recently, homosexuality among politicians was a well-kept secret shared by only a few initiates.

In fact, national representation in France is portrayed as the guardian of

family

and

heteronormativity

. The model of the (male) politician has long been depicted as a father figure who upholds the Civil Code (the basis of French law), which has made the family, and by association,

marriage

, one of the fundamental pillars of society. The idea remains to this day; even though the right to divorce was adopted in 1884 (first added to French law after the Revolution, it was abrogated during the Restoration), over 100 years later, the announcement in the 1990s by former French Prime Minister Michel Rocard that he was divorcing created quite a stir. It was clear that a male politician in France, even at the end of the twentieth century, needed to be married and, as much as possible, be a father. It was this idea that also spurred then-presidential candidate François Mitterrand, during France’s 1981 national election (which he would win), to advise the young, single ministerial hopefuls in his entourage that they must be married if they were to receive a portfolio in his government. Under these circumstances then, how is it possible for politicians to engage in relationships other than those established as the “norm,” even if that norm is discreetly transgressed, as evidenced by Mitterand’s well-known but unspoken “other family,” the result of an affair?

What was essential then was that the politician must serve as a model to the “good people.” Homosexuality was considered even more taboo than extramarital relations. But of course, French politicians were not all exclusively heterosexual. And thanks to Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès (1753–1824)—the French statesman and author of the Civil Code who, history tells us, was himself homosexual—sodomy ceased to be considered a crime. From its birth as a modern democracy, France no longer penalized homosexual relations, but did find it appropriate to ensure the clear division between genders in public life. Thus, by an order of November 7, 1800, it was forbidden for women to dress as men without the prefect’s authorization. However, until World War II, save for another order that forbade those dressed in the clothing of the opposite gender from attending public events or celebrations, men were not tried for transvestism.

In truth, French legislators ignored homosexuality until 1942; until then, it was up to the police and the legal system, in the name of respecting “good character,” to pursue anyone whose behavior was deemed to be “deviant” and put them on file. The fact that during World War II, the French state under the Vichy government introduced a law criminalizing homosexuality is not,

a priori

, surprising; in Vichy France, moral order was triumphant. However, it may be surprising that the law was not repealed after the war, when the Republic was restored, though one must remember that the years and, in fact, decades following France’s liberation were marked by a desire to uphold the idea of the “family,” a belief shared by the entire political spectrum from the Mouvement républicain populaire (Popular Republican Movement) to the Communist Party. It is in this context that the

Mirguet

amendment was passed in France in 1960, which officially turned homosexuality into a “social scourge.” During this time, homosexual rights were not an issue; the question was not the object of debate in Parliament, and in society at large, there was no discussion of the need to evolve. The major gay movement in France, Arcadie, was resolutely reformist—certainly, it criticized existing laws and demanded their repeal—but it was locked in the dilemma of the period that tended to separate public and

private

life. Even though Arcadie lobbied politicians for change, it did not make homosexuality a specifically political question. An abrupt change came about, however, in 1968, when gay and lesbian associations finally presented and defined themselves as political.

The pressure exerted by these new groups had an impact on politicians, to the point that the progressive parties, notably the Socialist Party, seriously listened to their demands. “Until the 1980s,” wrote Jean Danet, “homosexuality’s social situation had this consequence: the affective relationship between two persons of the same sex did not solicit much legal intelligence.” Homophobia, as defined by Daniel Borrillo, was “liberal”: homosexuality was tolerated if it remained discreet. It remained, however, that the law discriminated against homosexuals. In 1982, a year after the Socialist Party was elected to power, it corrected the situation (despite a strong resistance from conservative politicians) by revising Article 331 of France’s Penal Code, which had been originally written by the Vichy regime during World War II, maintained by the restored Republic, and made even worse in 1980 (with the addition of a paragraph that allowed for the punishment of relations between minors). Following the vote on the law on August 4, 1982, homosexuality could no longer be suppressed. Thereafter, political battles regarding homosexuality in France shifted to the fight for the legal recognition of same-sex couples, who did not enjoy the same rights as unmarried heterosexual couples.

Illustration for

Les Enfants de Sodome à l’Assemblée nationale ou Députation de l’ordre de la Manchette aux représentants de tous les orders

…,1790. A practical joke of the Revolution that, despite its outrageous demands and burlesque humor, is nothing less than a sincere plea for sexual freedom.

This new debate, which started in the 1990s, revealed that homophobia, both in the political world and in French society in general, was more than latent. A petition was presented by family associations to some 36,500 French mayors demanding that potential contracts between same-sex couples not be registered. The huge anti-PaCS demonstration of January 31, 1999—against the controversial civil union pact proposed by the government which granted rights (short of marriage) to unmarried couples, gay or straight— brought out tens of thousands of French citizens mobilized by

right-wing

associations and

Catholic

and fundamentalist groups. In Parliament, discussion of PaCS revealed that while the question divided most politicians along party lines, there were even those on the left who were difficult to persuade. During its first reading in the National Assembly, in fact, the proposition was rejected due to insufficient participation by the majority in session. Among other things, the debate unleashed in some politicians an explicit homophobia notable for its vulgarity (“Homosexuals, I piss in their asses,” was the declaration of Union pour la démocratie française (UDF; Union for French Democracy) Member of Parliament Michel Meylan) and provocation (according to UDF Senator Emmanuel Hamel, “PaCS” was short for “Practice of AIDS Contamination”).

The debate in France on PaCS, and the one on gay parenting that followed, had the effect of re-politicizing the question of homosexuality. While those on the left (with a few exceptions) generally supported PaCS, the question of gay

parenting

, in particular

adoption

by same-sex partners, was more nebulous. A parliamentary petition to forbid adoption by homosexuals, launched by Member Renault Musellier, was signed only by members of the right; however, very few on the left openly opposed it.

As a result of such debates, certain French politicians decided it was time to publicly declare their homosexuality. Though the number who have come out remains small, some have offered personal accounts of their experiences, particularly in the context of their political affiliation. Nonetheless, as a rule of thumb, elected officials in France remain discreet about their private lives, especially when those lives are not traditional. This issue brings up the question of

outing

public personalities, especially when they take homophobic positions or associate themselves with homophobic demonstrations such as the 1999 anti-PaCS protest. The political world, with a few exceptions, remains guarded on emerging social issues, and on homosexuality in particular. Even if the sociology of France’s political world has evolved (in 1999,

ProChoix

magazine counted 171 MPs who were not married), in general, elected officials remain wary of offending their constituents. But what about the “gay and lesbian vote”? Does it exist in France? Conversely, what about openly homophobic politicians and the impact of their views on voters? These questions are not easily answered, although numerous homophobic officials have been reelected.