The Grand Alliance (64 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

The Grand Alliance

389

doubtful whether in this condition she was a match for the

Bismarck.

Admiral Wake-Walker, therefore, decided not to renew the action, but to hold the enemy under observation.

In this he was indisputably right.

The

Bismarck

would indeed have been wise to rest content with what amounted by itself to a resounding triumph. She had destroyed in a few minutes one of the finest ships in the Royal Navy, and could go home to Germany with a major success. Her prestige and potential striking power would rise immensely, in circumstances difficult for us to measure or explain.

Moreover, as we now know, she had been seriously injured by the

Prince of Wales,

and oil was leaking from her heavily. How then could she hope to discharge her mission of commerce destruction in the Atlantic? She had the choice of returning home victorious, with all the options of further enterprises open, or of going to almost certain destruction. Only the extreme exaltation of her Admiral or the imperious orders by which he was bound can explain the desperate decision which he took. When I saw my American friend at about ten o’clock, I had already learned that the

Bismarck

was steaming southward, and I was, therefore, able to speak with renewed confidence about the final result.

I had to read for very long hours each day to keep abreast of the ceaseless flow of military, Foreign Office, and Secret Service telegrams, which streamed in by private telephone and dispatch-riders. This was a great comfort, because as long as one is doing something the mind is saturated and cannot worry. Nevertheless, only one scene riveted my background thoughts: this tremendous

Bismarck,

forty-five The Grand Alliance

390

thousand tons, perhaps almost invulnerable to gunfire, rushing southward towards our convoys, with the

Prinz

Eugen

as her scout. Then I thought of these convoys. Their battleships had left during the hunt. There was the troop convoy, with all its precious men on board, now well to the south of Ireland, with Admiral Somerville closing it at full speed, and presently to be between it and peril. I questioned the duty captain about times and distances. His reports were reassuring. Although the convoy only made about twelve knots and the

Bismarck

could, so far as we knew, do twenty-five, there was a lot of salt water between them. Besides, as long as we could hold fast to the

Bismarck

we could dog her to her doom. But what if we lost touch in the night? Which way would she go? She had a wide choice, and we were vulnerable almost everywhere.

The House of Commons, too, might be in no good temper when we met on Tuesday. They had been blown out of their Chamber on May 10 and were now crammed into the Church House, not far away. This was indeed a port in a storm, but there were no conveniences. Writing-rooms, smoking-rooms, dining-rooms, all the customary facilities, were improvised and primitive. The air-raid alarms were frequent and means for Members getting about scarce.

How would they like to be told on Tuesday when they met that the

Hood

was unavenged, that several of our convoys had been cut up or even massacred, and that the

Bismarck

had got home to Germany or to a French-occupied port, that Crete was lost, and evacuation without heavy casualties doubtful? I had great confidence in their pluck and fidelity if once they could be convinced that their business was not being muddled. But could they be? My American guest thought I was gay, but it costs nothing to grin.

The Grand Alliance

391

All through the twenty-fourth the British cruisers and the

Prince of Wales

continued to dog the

Bismarck

and her consort. Admiral Tovey, in the

King George V,

was still a long way off, but signalled that he hoped to engage by 9 A.

M. on the twenty-fifth. The Admiralty summoned all forces.

The

Rodney,

five hundred miles away to the southeast, was ordered to steer a closing course. The

Ramillies

was ordered to quit her homeward-bound convoy and place herself to the westward of the enemy; and the

Revenge,

from Halifax, was also directed to the scene. Cruisers were posted to guard against a break-back by the enemy to the north and east, while all the time Admiral Somerville’s force was pressing northward from Gibraltar. Subject to all the uncertainties of the sea, the net was drawing tighter.

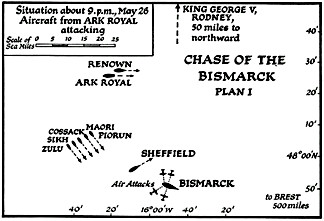

That evening about 6.40 the

Bismarck

suddenly turned to engage her pursuers, and there was a brief encounter. We now know that this movement was made to cover the escape of the

Prinz Eugen,

which then made off at high speed to the south, and after refuelling at sea reached Brest unchallenged ten days later. Admiral Tovey had sent the

Victorious

ahead to make an air attack in the hope of reducing the enemy’s speed. The

Victorious

was newly commissioned, and some of her air crews had little fighting experience. At 10 P.M., covered by four cruisers, she released her nine Swordfish torpedo-aircraft on a hundred-and-twenty-mile flight against a strong head wind with rain and low cloud. Led by Lieutenant-Commander Esmonde and guided by the

Norfolk’s

wireless, the aircraft two hours later

1

found the

Bismarck,

and attacked with great gallantry against intense fire. They scored a torpedo hit under the bridge. On board the

Victorious

the question of

The Grand Alliance

392

the recovery of the air squadron was causing acute anxiety.

By now it was pitch-dark, with a high wind and blinding showers of rain, and the pilots had had little practice in deck-landing even in daylight. Furthermore, the homing beacon, by which alone they could be safely guided to the ship, had failed. Despite any prowling U-boats, searchlights and signal lamps were used to help the pilots in their approach.

It is pleasant to record that their splendid efforts were rewarded. All succeeded in landing safely in the darkness amidst general rejoicing and relief.

Once more everything seemed to be set for a morning climax, and once more the Admiralty hopes were dashed.

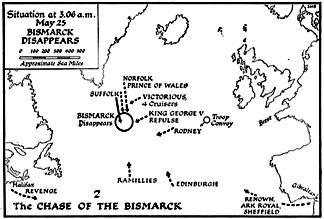

Soon after 3 A.M. on the twenty-fifth the

Suffolk

suddenly and unexpectedly lost contact with the

Bismarck.

She had been shadowing by radar with skill from a position on the enemy’s port quarter. All ships were now zigzagging as they moved south into waters infested by U-boats, and it was this which brought about the misfortune. At the end of each The Grand Alliance

393

outward leg of her zigzag course the

Suffolk

lost radar contact, but regained it on the inward leg. Perhaps she was overconfident after such prolonged and successful shadowing. But now when she turned once more to the westward the enemy was no longer on the presumed course. Had he turned west or doubled back to the north and east? This caused the utmost anxiety and rendered all concentration futile. After making a cast to the westward at daylight the

King George V

turned eastward in the belief that the

Bismarck

was making towards the North Sea, and the whole British pursuit now trended in this direction. At the Admiralty there was a growing opinion that the

Bismarck

was steering for Brest, but it was not until six o’clock that this hardened. The Admiralty forthwith deflected all our forces towards the more southerly route. But meanwhile the confusion and delay arising from the loss of contact had enabled the

Bismarck

to slip through the cordon and gain a commanding lead in her race for safety. By 11 P.M. she was already well to the eastward of the British flagship. She was short of oil through the leakage. The

Rodney,

with her sixteen-inch guns, still lay between her and home, but she too was moving to the northeastward and crossed ahead of the

Bismarck

during the afternoon. The day which had begun so full of promise ended in disappointment and frustration. Happily, from the south, breasting the heavy Atlantic seas, the

Renown,

the

Ark Royal,

and the cruiser

Sheffield

were steadily approaching on an intercepting course.

The Grand Alliance

394

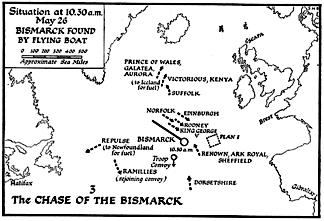

By the morning of May 26 the problem of fuel for all our widely scattered ships, which had now been steaming hard for four days, began to clamour for attention. Already several of the pursuers had had to reduce speed. It was clear that in these wide expanses all our efforts might soon be vain. However, at 10.30 A.M., just as hopes were beginning to fade, the

Bismarck

was found again. The Admiralty and Coastal Command were searching with Catalina aircraft working from Lough Erne in Ireland. One of these now located the fugitive steering towards Brest and still about seven hundred miles from home. The

Bismarck

damaged the aircraft and contact was lost. But within an hour two Swordfish from the

Ark Royal

spotted her once more. She was still well to the westward of the

Renown

and not yet within the German air cover radiating powerfully from Brest. The

Renown,

however, could not face her single-handed. It was necessary to await the arrival of the

King George V

and

Rodney,

both still far behind the chase.