The Grand Alliance (78 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

Prime

Minister

to

25 July 41

Monsieur Stalin

I am glad to inform you that the War Cabinet have

decided, in spite of the fact that this will seriously

deplete our fighter aircraft resources, to send to Russia

as soon as possible two hundred Toma-hawk fighter

airplanes. One hundred and forty of these will be sent

from here to Archangel, and sixty from our supplies in

the United States of America. Details as to spare parts

and American personnel to erect the machines have

still to be arranged with the American Government.

2. Up to two to three million pairs of ankle boots

should shortly be available in this country for shipment.

We are also arranging to provide during the present

year large quantities of rubber, tin, wool and woollen

cloth, jute, lead, and shellac. All your other requirements from raw materials are receiving careful consideration. Where supplies are impossible or limited from

The Grand Alliance

477

here, we are discussing with the United States of

America.

Details will of course be communicated to the usual

official channels.

3. We are watching with admiration and emotion

Russia’s magnificent fight, and all our information

shows the heavy losses and concern of the enemy. Our

air attack on Germany will continue with increasing

strength.

Rubber was scarce and precious, and the Russian demand for it was on the largest scale. I even broke into our modest reserves.

Prime

Minister

to

28 July 41

Monsieur Stalin

Rubber. We will deliver the goods from here or

United States by the best and quickest route. Please

say exactly what kind of rubber, and which way you

wish it to come. Preliminary orders are already given….

3. The grand resistance of the Russian Army in

defence of their soil unites us all. A terrible winter of

bombing lies before Germany. No one has yet had

what they are going to get. The naval operations

mentioned in my last telegram to you are in progress.

Thank you very much for your comprehension in the

midst of your great fight of our difficulties in doing more.

We will do our utmost.

Prime

Minister

to

31 July 41

Monsieur Stalin

Following my personal intervention, arrangements

are now complete for the dispatch of ten thousand tons

of rubber from this country to one of your northern ports.

In view of the urgency of your requirements, we are

taking the risk of depleting to this extent our metropolitan stocks, which are none too large and will take time

to replace. British ships carrying this rubber, and certain

other supplies, will be loaded within a week, or at most

ten days, and will sail to one of your northern ports as

The Grand Alliance

478

soon as the Admiralty can arrange convoy. This new

amount of ten thousand tons is additional to the ten

thousand tons of rubber already allotted from Malaya.

I tried my best to build up by frequent personal telegrams the same kind of happy relations which I had developed with President Roosevelt. In this long Moscow series I received many rebuffs and only rarely a kind word. In many cases the telegrams were left unanswered altogether or for many days.

The Soviet Government had the impression that they were conferring a great favour on us by fighting in their own country for their own lives. The more they fought, the heavier our debt became. This was not a balanced view.

Two or three times in this long correspondence I had to protest in blunt language, but especially against the ill-usage of our sailors, who carried at so much peril the supplies to Murmansk and Archangel. Almost invariably however I bore hectoring and reproaches with “a patient shrug; for sufferance is the badge” of all who have to deal with the Kremlin. Moreover, I made constant allowances for the pressures under which Stalin and his dauntless Russian nation lay.

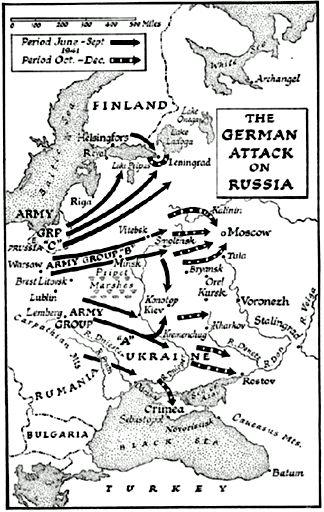

The German armies in Russia had driven deep into the country, but at the end of July there arose a fundamental clash of opinion between Hitler and Brauchitsch, Commander-in-Chief. Brauchitsch held that Timoshenko’s Army Group, which lay in front of Moscow, constituted the main Russian strength and must first be defeated. This was The Grand Alliance

479

orthodox doctrine. Thereafter, Brauchitsch contended, Moscow, the main military, political, and industrial nerve centre of all Russia, should be taken. Hitler forcefully disagreed. He wished to gain territory and destroy Russian armies on the broadest front. In the North he demanded the capture of Leningrad, and in the South of the industrial Donetz Basin, the Crimea, and the entry to Russia’s Caucasian oil supplies. Meanwhile Moscow could wait.

The Grand Alliance

480

The Grand Alliance

481

After vehement discussion Hitler overruled his Army chiefs.

The Northern Army Group, reinforced from the centre, was ordered to press operations against Leningrad. The German Centre Group was relegated to the defensive.

They were directed to send a Panzer group southward to take in flank the Russians who were being pursued across the Dnieper by Rundstedt. In this action the Germans prospered. By early September a vast pocket of Russian forces was forming in the triangle Konotop-Kremenchug-Kiev, and over half a million men were killed or captured in the desperate fighting which lasted all that month. In the North no such success could be claimed. Leningrad was encircled but not taken. Hitler’s decision had not been right.

He now turned his mind and will-power back to the centre.

The besiegers of Leningrad were ordered to detach mobile forces and part of their supporting air force to reinforce a renewed drive on Moscow. The Panzer group which had been sent south to von Rundstedt came back again to join in the assault. At the end of September the stage was reset for the formerly discarded central thrust, while the southern armies drove on eastward to the lower Don, whence the Caucasus would lie open to them.

The attitude of Russia to Poland lay at the root of our early relations with the Soviets.

The German attack on Russia did not come as a surprise to Polish circles abroad. Since March, 1941, reports from the Polish underground upon German troop concentrations on the western frontiers of Russia had been reaching their Government in London. In the event of war a fundamental change in the relations between Soviet Russia and the Polish Government in exile would be inevitable. The first The Grand Alliance

482

problem would be how far the provisions of the Nazi-Soviet Pact of August, 1939, relating to Poland could be reversed without endangering the unity of a combined Anglo-Russian war alliance. When the news of the German attack on Russia broke upon the world, the re-establishment of Polish-Russian relations, which had been broken off in 1939, became important. The conversations between the two Governments began in London under British auspices on July 5. Poland was represented by the Prime Minister of her exiled Government, General Sikorski, and Russia by the Soviet Ambassador, M. Maisky. The Poles had two aims –

the recognition by the Soviet Government that the partition of Poland agreed to by Germany and Russia in 1939 was now null and void, and the liberation by Russia of all Polish prisoners of war and civilians deported to the Soviet Union after the Russian occupation of the eastern areas of Poland.

Throughout the month of July these negotiations continued in a frigid atmosphere. The Russians were obstinate in their refusal to make any precise commitment in conformity with Polish wishes. Russia regarded the question of her western frontiers as not open to discussion. Could she be trusted to behave fairly in this matter in the possibly distant future, when hostilities would come to an end in Europe? The British Government were in a dilemma from the beginning.

We had gone to war with Germany as the direct result of our guarantee to Poland. We had a strong obligation to support the interest of our first ally. At this stage in the struggle we could not admit the legality of the Russian occupation of Polish territory in 1939. In this summer of 1941, less than two weeks after the appearance of Russia on our side in the struggle against Germany, we could not force our new and sorely threatened ally to abandon, even on paper, regions on her frontiers which she had regarded for generations as vital to her security. There was no way The Grand Alliance

483

out. The issue of the territorial future of Poland must be postponed until easier times. We had the invidious responsibility of recommending General Sikorski to rely on Soviet good faith in the future settlement of Russian-Polish relations, and not to insist at this moment on any written guarantees for the future. I sincerely hoped for my part that with the deepening experience of comradeship in arms against Hitler the major Allies would be able to resolve the territorial problems in amicable discussion at the conference table. In the clash of battle at this vital point in the war, all must be subordinated to strengthening the common military effort. And in this struggle a resurgent Polish army based on the many thousands of Poles now held in Russia would play a noble part. On this point the Russians were prepared to agree in a guarded fashion.

On July 30, after many bitter discussions, agreement was reached between the Polish and Russian Governments.

Diplomatic relations were restored, and a Polish army was to be formed on Russian soil and subordinated to the supreme command of the Soviet Government. There was no mention of frontiers, except a general statement that the Soviet-German treaties of 1939 about territorial changes in Poland “have lost their validity.” In an official Note of July 30