The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (49 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Edmonia often spoke of her half-brother, but it seems she guarded his name.

[821]

She called him either “my brother” or “Sunrise,” as if he were from the Indian side of her family. She once identified a bust she modeled in 1867 as “my uncle, Sunrise.”

[822]

This could only confuse snoops. Elizabeth Peabody thought him dead. Anne Whitney knew better. His identity remained secret, protected, long after Edmonia disappeared. To anyone interested in knowing more about her, he became an important mystery.

One day in 1975, an art educator named Eileen Tenney moved to Bozeman, where she took interest in an old rundown house with a gabled roof, frescoed ceiling, stained glass transoms, and too many exits. Every first floor room had a door to the outside – a feature that provokes questions without ready answers.

The first realtor she called refused to show it, saying, you do not want to live there. Mysteriously drawn to the house, Mrs. Tenney prevailed on another. She recalled she felt as if she and her husband were meant to live there. They soon bought it and moved in.

[823]

They had experienced such magnetism before. Years earlier, they had been attracted to the poorest country in the hemisphere, Haiti. There her husband, Richard, a cardiologist, volunteered for a time at Hôpital Albert Schweitzer in Des Chapelles.

The Tenneys were originally from South Dakota, a society as remote from the Creole-speaking tropics as one might find.

They soon fell in love with the island’s art and culture. They later returned, traveling to Port au Prince and Cap Haitian, buying colorful paintings, woven rugs, and art made from wood and metal. In Bozeman, they filled the ample house with treasures from the island republic.

Two years later, an architecture student from Montana State University knocked on their door, asking if they knew the history of the house. The student told them Samuel W. Lewis built it in 1881. She had his obituary indicating his Haitian birth and famous sister.

The Haitian connection resonated profoundly. Later, browsing in a bookstore, Eileen came across a photo of Edmonia and instantly decided to devote her master’s thesis to Edmonia’s life and art. She developed a school program where she, dressed as Harriet Hosmer, taught about Edmonia using music, art, drama, and dance.

In early 1991, she attended a celebration of Edmonia’s work at the San Jose Martin Luther King Jr. Library. There she identified the mysterious ‘Sunrise.’ Word soon spread through the art history community.

Lewis, with his wife Melissa and his only son Samuel E., rest in the Bozeman cemetery. His son died in Chicago at the age of 30 years old. His death certificate says the cause was heart disease.

[824]

In 1999, the National Register of Historic Places added the Queen Anne style, brick building.

[825]

Like the letters received by the unsentimental Child, who fed them to her stove on chilly nights or used their blank sides to write on, nothing of the long brother and sister correspondence survives.

Works listed below were mentioned by contemporary correspondence and the press. We note copies in public collections. Most works also appear in the text above, where alternative names may be used, with notes. Additional sources are cited here. Few works have been examined by the authors. Measurements and inscriptions are from secondary sources and have not been verified. Some works may be duplicated in error thanks to a repetitive press. The chronological order is approximate and the numbering is arbitrary. Some works listed are seemingly lost, never completed, missing, destroyed, or subject to error. Some reports are unsubstantiated; some describe student work. SIRIS and the Edmonia Lewis web site (http://www.edmonialewis.com) provide updates, more details, and links to images of some items.

1. Drawing of the Muse, Urania.

Oberlin College Archives, Oberlin, OH. (Figure 1).

1863 Boston

3. Bust of Voltaire.

4. Medallion of John Brown.

5. Medallion of William Lloyd Garrison.

6. Medallion of Wendell Phillips.

1864

7. Bust of Col. Robert Gould Shaw.

Plaster. Photo, Massachusetts Historical Society (Figure 4). Marble, 1867, Afro-American Museum, Boston, MA.

9. Medallion of Senator Charles Sumner.

1865

10. Bust of Maria Weston Chapman.

Plaster. Tufts Free Library, Weymouth, MA (Figure 6).

12. Bust of William Wallace Hebbard.

13. Medallion of Abraham Lincoln.

14. Bust of Abraham Lincoln.

15. Bust of John Brown.

16. Bust of Wendell Phillips.

17. Bust of Horace Mann.

18. Bust of Dioclesian Lewis.

Plaster, 1865; Marble 1866; Marble, 1868, 22.5 in., Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD. (Figure 19).

19. The Freed Woman and Her Child.

20. Second bust of Col. Robert Gould Shaw.

21. Bust of Helen Ruthven Waterston

(once thought to be Anna Quincy Waterston). Marble, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. (Figure 12).

23. Preghiera [Prayer].

Marble, 22 in.

[826]

a) Marble, 1871, 31.5 in., Cincinnati Art Museum (on loan), Cincinnati, OH. b) Marble, 1872, Kalamazoo Institute of Art, Kalamazoo MI. c) Marble, 32.25 in., 1874, Stark Museum of Art, Orange, TX (Figure 9). d) Marble, 29.5 in., 1868, Montgomery Museum of Fine Art, Montgomery, AL.

a) Marble, 1866, 24 in., Walker O. Evans Center at Savannah College of Art and Design Museum of Art, Savannah, GA. b-c) Marble, 1872, 21.5 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC (2 copies) (Figure 10). d) Marble, 1872, 23.5 in., Tuskegee University. e) Marble, 1872, 20 in. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR.

26. Third group from The Song of Hiawatha.

[827]

27. Bust of Uncle Sunrise.

Terra cotta.

Terra cotta.

Terra cotta.

sic

Nokomis].

[828]

31. Forever Free.

Marble, 41.25 in., Howard University, Washington, DC. (Figure 23; Started in 1866 as

Morning of Liberty).

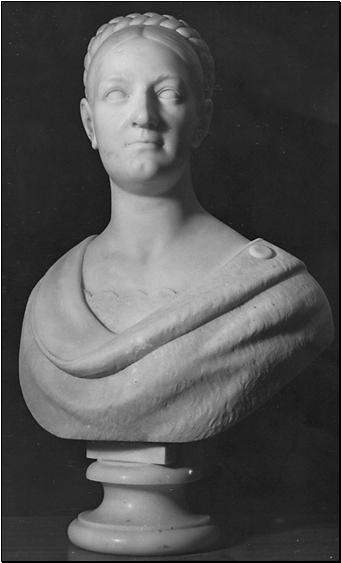

Figure 52. Bust of a Woman with plaited hair, 1867

Once thought to portray a New Englander, this early portrait might depict one of the English Catholics who supported Edmonia after she arrived in Rome. Note how this marble appears in modern dress. Photo: Fred Levenson

Marble, 27 in., Harmon and Harriet Kelley Foundation for the Arts, San Antonio, TX. (Figure 52)

33. Madonna groups.

34. Soldier.

[829]

35. Hagar (Hagar in the Wilderness).

Marble, 52 5/8 in., 1875, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC (Figure 26)

Engraving.

Marble, 30 in., Cleveland Museum of Art (Figure 24).

[830]

39. Bust of Hiawatha.

a) Marble, 14.25 in., Newark Museum, Newark, NJ.

(Figure 22).

b) Marble, 1869, 16.25 in., Howard University, Washington, DC.

a) Marble, 11 in., Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI. b) Marble, 12.25 in., Newark Museum, Newark, NJ.

(Figure 21).

c) Marble, 1869, 11.5 in., Howard University, Washington, DC.

42. Clio.

43. Bust of a Bearded Gentleman.

Marble, 22 in.

[831]

44. Bust of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

a) M

arble, 28.7 in., 1871,

Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. b) Marble, 25.8 in., 1872, Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool, England (Figure 27).

Plaster painted to resemble terra-cotta (Figure 28).

47. Bust of infant Edith (“Violet”) Forbes.

48. Madonna with the infant Christ in her arms, and two adoring angels at her feet.

For the Marquess of Bute.

49. Medallion of Franz Liszt.

50. Clytie Turned into a Sunflower.

51. Night.

Marble, 24 in. Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD. (An early version of Asleep.)

52. Madonna and Child.

For St. Francis Xavier church / Oblate Sisters of Providence in Baltimore.

[832]

Marble, signed, 18 ¼ inches in diameter. (Figure 3).

55. Awake.

a) Marble, 1872, San Jose Public Library, San Jose, CA. b) Marble, 20 ½, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, AL.

Marble, 1871, San Jose Public Library, San Jose, CA. (Figure 33).

Marble, 27 in., 1876, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC (Figure 34).

Marble.

Marble on a marble base and a granite block, 4 ft., 4 in., Memorial for Dr. Harriot Hunt, Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (Figure 29).

61. Bust of Abraham Lincoln.

Marble, 1871, San Jose Public Library, San Jose, CA. (Figure 39).

(attributed) Marble, 36 in. Cf. 1880, Rebekah, below

63. Bust of Horace Greeley.

64. Bust of Abraham Lincoln with four miniature (two men, two women) figures.

Marble, 39 in.

65. Bust of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

[833]

(attributed) Marble, about 15 in. high. (Figure 54).

[835]

67. Bust of Young Octavian (Young Augustus).

Marble, 16 in., Smithsonian American Museum of Art, Washington, DC. (Figure 36).

Marble, 23 in., St. Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO. (Figure 38).

69. Bust of James Peck Thomas.

Marble, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH. (Figure 37).

70. Moses (after Michelangelo).

Marble, 26 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. (Figure 41).

Marble; Plaster painted to resemble terra-cotta (Figure 45).

72. Bust of John Brown.

Plaster painted to resemble terra-cotta (Figure 44).

Marble, 63 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. (Figure 42).

Plaster painted to resemble terra-cotta, Wilberforce University, Wilberforce, OH. (Figure 46).

(apocryphal).

[836]

(apocryphal).

77. Monument to Lyman Blair.

[837]

78. Madonna and Child.

[838]

79. St. Joseph.

[839]

80. Madonna.

[840]

81. Bust of President U. S. Grant.

82. Bust of Bishop Thomas Patrick Roger Foley.

83. Bust of John Brown.

Marble, Presented to Rev. Henry Highland Garnet.

[841]

(apocryphal)

[842]

1879

86. Virgin at the Cross with base and pedestal.

Memorial for the grave of Pelagie Rutgers in St. Louis (confirmed lost).

Marble, 48 in. (Figure 48-49)

Plaster, patinated to resemble bronze. American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY. (Figure 50).

89. ‘Veiled’ Spring.

90. Rebekah.

Marble, 59 in.

[843]

Cf. 1871,

Rebecca at the Well.

91. Adoration of the Magi.

[844]

1884