The Lightning Keeper (51 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

He had no religion, but signs and apparitions were different; they always meant something. When he had spoken with Steinmetz, trying to pierce that maddening forbearanceâthe victor's magnanimity, as it would turn outâhis only thought had been: This must be punished. Only minutes later he was looking at her, and she at him, and in that moment vengeance took a specific shapeâthis planâand was in the same instant reframed, transformed. He would do it for her. He loved her more than he detested Steinmetz. Now Tesla had visited him and the ground shifted again, taking away all his doubt. He would do this for himself, and he alone would know

. I will take it back. It is mine

. His body went rigid with anticipation of the deed, and the danger. And the rain came.

There was a portion of the roof just below his window ledge and he worked his way around the corner until he found the drainpipe. If he felt it starting to give way, he would drop into the bed of shrubbery below so that it wouldn't fall. How he would scale the wall again in that

case he had no idea, but he was no longer concerned with what might go wrong.

The path was muddy and of course steep, but he knew every rock and root of it. He went as fast as he dared, and faster when he had the help of the lightning. In the tangle of wires laid this morning there was only one that he needed. It had been strung through the scrub oaks to reach a battery of rockets around the shoulder of the Knob. Too much slack in that wire, he had said to the cable technician, who shrugged and replied: All this comes down tomorrow. Somebody would remember that exchange.

He was out now on the bare top of the Knob, with the aerial and the tower at his back. The storm had come across the valley of the Buttermilk and was so close that there was almost no delay between the lightning and its thunder. He could even smell flint, which made him think that there had already been a strike here. He walked out to where he thought the wire should be and waited for another flash.

He saw the wire and remembered Stefan's story. If lightning had already struck here there might be a residual charge in this wire, and he would be the ground when he touched it. There was no time and no choice: the next bolt might kill him as surely as the last one. He took it in his hand and knew that tonight he was immortal. The lightning would do his bidding.

He had worried about the arresters and the fuses, but with this fire in his mind he did not have to think any more. He took a branch, heavier than the wire, lighter than the wind, and wedged them both against the stout conduit below the fuse box. There was now nothing but a few thousand feet of cable between him and the silk mill, between the lightning and the wheel. He followed the wire back toward the aerial in the open embrasure of the tower, pulling a bit of slack from the far end as he went, leaving his anchor undisturbed. The lightning would jump from the aerial to a cable, but he must leave nothing to chance. He ran his hand down the aerial to the collar at its base and looped his wire once around a bolt. One hand on the wire, the other on the aerial, he felt the sodden hair rising on the back of his neck. He would walk, not run, for he had nothing to fear.

I am the lightning

.

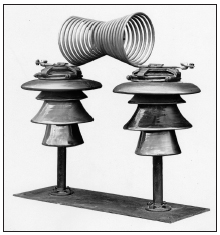

70,000-volt choke coil for use with lightning arrester

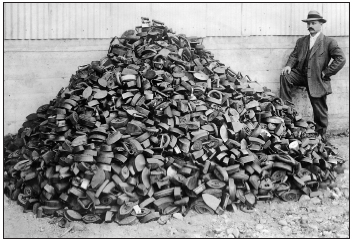

Pile of 2,000 old flat irons taken in exchange for electric irons

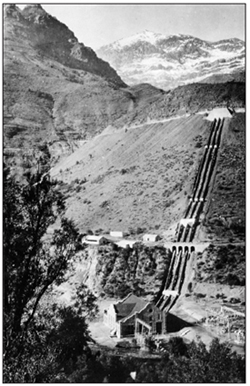

High-head hydroelectric plant in Chile, 1923

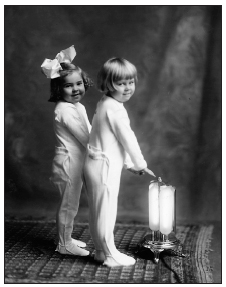

Minnesota farmer with his electrically driven cream separator, 1924

It is a mystery why this man has such hatred for me, and why he should go to such lengths to punish the firm that has raised him from obscurity. Of course I regret my remarks, and I have already offered my profound apology in a personal letter. But I insist that the publication of those characterizations of him was a complete misunderstanding; it was something written in the heat of the moment and appended as a postscript to my account of the catastrophic events in Beecher's Bridge. The article itself was typed, as all my contributions to the

Journal of Advanced Engineering

have been, and the remarks, which you see for yourself are handwritten, were a personal and private communication from myself to the editor. I meant merely to suggest a possibility, a theory without proof, concerning the circumstances that led to the fire in the Experimental Site and the destruction of the Peacock Turbine.

âfrom the deposition of C. P. Steinmetz in the action

Peacock v. General Electric et al.

Much has been written and still more said concerning the fire that destroyed the Experimental Site and effectively ended General Electric's salutary endeavors in our town, and in the desired event that my own history should one day be published, I will not enter into any dangerous speculations as to the causes of that conflagration. It seemed, and this is still the opinion of most folk in Beecher's Bridge, to be an act of God.

The Experimental Site might have been rebuilt, given time and goodwill, and absent the distraction of the war. But the publication of Dr. Steinmetz's allegedly defamatory remarks cast a pall over relations between the principals, and the libel action pursued by Mr. Peacock was not resolved until after the war had ended. The case never came to trial, but was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount of money. Also, and perhaps more significantly, the rights to the Peacock Turbine were reverted to the inventor. The work that Dr. Steinmetz envisioned was never resumed or pursued, but in 1922 he perfected the artificial generation of lightning in the GE laboratories in Schenectady.

The tower still stands on Lightning Knob, and it is still known as Peacock's Folly. The water of Dead Man's Lake follows its natural course down the mountain through Rachel's Leap to the placid, unaltered pond below the Truscott house. It might seem, taking the long view, as if nothing ever changes in Beecher's Bridge, as if the words of the Congregational ministerâuttered in bitter dissent to the decision of the railroad commissionersâare an inescapable prophecy: the history of Beecher's Bridge is the history of failed enterprise.

But there is a nearer perspective in which everything changes: Senator Truscott dies, and after a suitable period of mourning, his widowâthe mother of his childâtakes as her husband that same Thomas Peacock who had lately been her chauffeur, then laborer in the ironworks, then, by some obscure stroke of fate, inventor. We do not have very rigid social distinctions in Beecher's Bridge, and yet this match is certainly the object of much curiosity and gossip. It would be one thing if she had simply been Harriet Bigelow, but her status as the widow of a United States senator altered how people, some people, looked upon the match, and they say it can come to no good.

I take a more charitable, or relaxed, view of the matter. People will find their own happiness, or the opposite, and how such things turn out often defies expectation or common wisdom. Indeed the chronicle of recent events in Beecher's Bridge, from what I term the nearer or human perspective, is nothing if not a series of astonishing, unforeseeable reversals and cataclysms. Which is why, perhaps, I take refuge in the longer and more peaceful perspective of history, and leave such unknowable things as the workings of the heart to the imagination of novelists.

I am very grateful indeed to the following people and organizations, whose collective efforts, enthusiasm, and generosity have sustained me in the researching and writing of this book:

For research on facts and photographs: Patricia Chui, John Crowley, Chris Hunter, Michaela Murphy, and Barry Webber.

For editorial guidance: Tim Duggan, Jonathan Galassi, and Earl Shorris.

For reading, sound advice, and other courtesies: Catherine Brown, Sarah Chalfant, Richard S. Childs, Starling W. Childs, Linda Corrente, Susan Corrente, Michael Hudnall, Nelle Harper Lee, Michael Lewis, Allison Lorentzen, James Mairs, Robert Morgan, Howard Norman, Jay Pittman, Jenny Preston, Allen Wheelis, John Williams, and Andrew Wylie.

For their erudition, which opened so many doors: Margaret Cheney

(Tesla)

; Theron Wilmot Crissey

(A History of Norfolk, 1744-1900)

; David Freeman Hawke

(Nuts and Bolts of the Past)

; Thomas P. Hughes

(Networks of Power)

; Ed Kirby

(Echoes of Iron);

Ronald R. Kline

(Steinmetz)

; J. Lawrence Pool

(America's Valley Forges and Valley Furnaces)

; Matthew Roth, Bruce Clouette, and Victor Darnell

(Connecticut: An Inventory of Historic Engineering and Industrial Sites;

Thomas J. Schlereth

(Victorian America).

Special thanks to the Corporation of Yaddo for allowing me two residencies, during which much of the writing was accomplished; to the

Norfolk Historical Society for making available its photographic collection documenting local Connecticut history; and to the Schenectady Museum for access to the extraordinary General Electric archive of documents and photographs pertaining to the history of the electric power industry.