The Marriage Book (13 page)

Authors: Lisa Grunwald,Stephen Adler

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #General, #Literary Collections

Thompson’s first marriage, to Hungarian writer Joseph Bard, lasted four years; her third, to artist Maxim Kopf, lasted fifteen, until his death. Lewis’s given name was Harry; he was often called “Hal” (also “Red” for his hair). “Give me Vermont” was an allusion to the house he and Thompson shared there. “Your two children” referred to Lewis’s son from a previous marriage and to Michael (“Mickey”), the son he and Thompson had together. The latter was sent to boarding school at the age of eight. Hamilton Fish Armstrong was editor of

Foreign Affairs

. Graham Hutton was an economist. “Faux [properly

faute

] de mieux” means

for lack of anything better

.

Hal:

If you think it’s wicked—go ahead and get a divorce. I won’t oppose it. I also won’t get it. For God’s sake, let’s be honest. You left me, I didn’t leave you. You want it. I don’t. You get it. On any ground your lawyers can fake up. Say I “deserted” you. Make a case for mental cruelty. You can make a case. Go and get it.

What is “incredible” about my not writing? What is “incredible” is that I don’t rush into the divorce court and soak

you

for desertion and “mental cruelty.” I don’t write because I don’t know what to say to you. You have made it clear time on end that you dislike me, that you are bored with me, that you are bored with “situations and conditions. And reactions.” You don’t like my friends. You don’t know my friends. You resent my friends. Shall I write you that I think Hamilton Armstrong has done a brilliant piece of journalism in his last book on the Munich conference? Or that Graham Hutton is in America and has a fascinating tale of Britain? . . . You are happy. Happier, you write, than you have been in years. I congratulate you. I am glad that you are happy. I happen not to be. I am not happy. I am not happy, because I have no home; because I have an ill and difficult child without a father. Because I have loved a man who didn’t exist. Because I am widowed of an illusion. Because I am tremblingly aware of the tragedy of the world we live in.

I do not “admire and respect you.” I have loved you. I do not admire your present incarnation or respect your present attitude toward anything. I did not like “Angela is 22” because I

think it is beneath the level of the author of “Arrowsmith” or of “It Can’t Happen Here.” I think it is a cheap concession to a cheap institution—the American Broadway Theater. I do not admire the people with whom you surround yourself. I am horrified, on your behalf, at the association of your name with that of Fay Wray. Why haven’t I said so? Out of tact! Out of the feeling that a great man may allow himself indulgences. Out of the desire not to hurt someone who is sensitive. . . .

When I am with you I depress you. I am depressed. But I would rather be depressed than pretend that nothing really matters. I don’t write to you because I can’t lie to you. Maybe it is because I respect you, or maybe it is because I respect myself—somewhat. I think you have thrown down the sink the best things that life has ever offered you: the love of friends; of your wife; the pleasure in your sons. Your home. For what? For whisky and art? Where’s the art, at long last? Or the whisky?

You say I am “brilliant.” My dear Hal, I am “brilliant” faux de mieux. I am a woman—something you never took the trouble to realize. My sex is female. I am not insensitive. I am not stupid. I do not love you for your wit, or for “nostalgia”—my nostalgia antedates our marriage. I loved you, funnily enough, for your suffering, your sensitivity, your generosity, and your prodigious talent. I shall not reiterate my feelings, nor insist that I still love you. I do not even know you—the you of the present moment. I shall certainly not pursue you, I am a woman. If you want my friendship you have got to win it. If you care for anything more, you have got to woo it. If you don’t—then you, be honest, as you advise me to be—and break this relationship finally and completely. Forget that I exist. Forget that Mickey exists. Wipe him out as a responsibility. Wipe me out as a memory. Be happy! Be free.

I, however, am not free. I can neither wipe out my memories, nor, above all, can I forget you, since you live with me, as the chief, perhaps the only tie I have to life, in the re-incarnation of yourself in your son. You have fathered a child, violent and frail, gifted, unbalanced, and charming, born to unhappiness, to ill-adjustment, to crazy joy and continual disappointment. Born to grow up in this tragic century. A sick, lovely, nerve-wracking, expensive child. He was conceived in a night that I remember, and you do not, and born in a night that I remember and that you[—]or do you? . . . There are things in my heart that you do not dream of, things that are compounded of passion and fury and love and hate and pride and disgust and tenderness and contrition[,] things that are wild and fierce[—]and you ask me to write you conventional letters because you are in “exile[.]” From what? From whom?

Give me Vermont. I want to watch the lilac hedge grow tall and the elm trees form, and the roses on the gray wall thicken, and the yellow apples hang on the young trees, and the sumac redden on the hills, and friends come, and your two children feel at home. Who knows?

Maybe some time you might come home yourself. You might go a long way and do worse. As a matter of fact and prophecy—you will.

d.

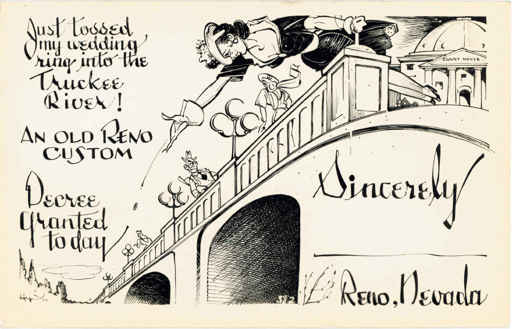

NEVADA POSTCARD, CIRCA 1940

Note the singular determination with which this divorcée is following the fabled custom of jettisoning her wedding ring from what became known in Reno, Nevada, as “The Bridge of Sighs.” In 1906, the wife of the adulterous head of U.S. Steel was granted a much-publicized divorce there; the resulting gossip put Reno ahead of any other Nevada or U.S. city as the country’s divorce destination. By 1931, when the “Severance Stay” to gain the required state residency was cut to six weeks, divorce became a lucrative industry and remained so during the Depression and for the next several decades. In the vernacular, “Going Reno” meant getting a divorce; columnist Walter Winchell called it getting “Reno-vated”; and in the 1940s “The Reno” was the name for a bra that was said to “separate and support.”

EDWARD ALBEE

WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF?

, 1962

About Albee and this play, see

Conflict

. Ellipses in original.

MARTHA: | I swear . . . if you existed I’d divorce you. . . . |

WOODY ALLEN

“MY MARRIAGE,” 1964

Eventually the writer and/or director of some half a hundred films (as well as being a successful playwright, actor, short story writer, and occasional jazz musician), Woody Allen (1935–) began his career as a teenager, selling jokes to newspaper columnists and, by nineteen, writing for television. In 1962, he and his childhood sweetheart, Harlene Rosen, divorced after six years of marriage, giving Allen not only his freedom but also a rich comic lode to mine for the stand-up career he pursued in the 1960s.

Allen’s second marriage, to actress Louise Lasser, lasted from 1966 to 1970. His twelve-year relationship with actress Mia Farrow ended in 1992, when he left Farrow for her twenty-year-old adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn. Previn and Allen have been married since 1997. CONELRAD was an emergency broadcasting system begun during the Cold War.

It was partially my fault that we got divorced. I had a lousy attitude toward her. For the first year of marriage I had a bad—basically a bad attitude, I guess. I tended to place my wife underneath a pedestal all the time.

We used to argue and fight. We finally decided, we either take a vacation in Bermuda or get a divorce, one of the two things. And we discussed it very maturely, and we decided on the divorce, ’cause we felt that we had a limited amount of money to spend, ya know. A vacation in Bermuda is over in two weeks, but a divorce is something that you always have.

And I saw myself free again, living in the Village, ya know, in a bachelor apartment with a wood-burning fireplace and a shaggy rug, and on the walls one of those great Picassos by Van Gogh, and just great swinging—airline hostesses running amok in the apartment, ya know. And I got very excited, and I ran into my wife. She was in the next room at the time, listening to CONELRAD on the radio, ya know. I laid it right on the line with her, I came right to the point, I said “Quasimodo, I want a divorce.”

NEIL SIMON

THE ODD COUPLE

, 1965

With myriad awards (including a Pulitzer) for dozens of successful plays and films, Neil Simon (1927–) has been one of America’s most productive and popular dramatists.

The Odd Couple

, one of his earliest works, is about two friends—one divorced, one recently separated—who share an apartment despite being temperamentally and hilariously unsuited. In this scene, the sportswriter slob Oscar Madison (played by Walter Matthau in both the play and its subsequent film adaptation) tries to explain his marriage to the neurotic neat freak Felix Ungar.

How can I help you when I can’t help myself? You think

you’re

impossible to live with? Blanche used to say,“What time do you want dinner?” And I’d say, “I don’t know, I’m not hungry.” Then at three o’clock in the morning, I’d wake her up and say “Now!” I’ve been one of the highest paid sports writers in the East for the past fourteen years—and we saved eight and a half dollars—in pennies! I’m never home, I gamble, I burn cigar holes in the furniture, drink like a fish and lie to her every chance I get and for our tenth wedding anniversary, I took her to the New York Rangers–Detroit Red Wings hockey game, where she got hit with a puck. And I

still

can’t understand why she left me. That’s how impossible

I

am.

“SHOULD THIS MARRIAGE BE SAVED?”

LADIES’ HOME JOURNAL

, 1970

Ladies’ Home Journal

launched the column “Can This Marriage Be Saved?” in 1953, and it has thrived since in various, book, TV, and digital formats. Seven years after Betty Friedan (see

Freedom

) described the dilemma of the suburban housewife in

The Feminine Mystique

, the

Journal

printed the story of “Barbara,” a thirty-three-year-old businessman’s wife and mother of three. The story made it clear that women’s perspectives were changing. “When she talked,” the author of the article wrote, “she did not ask herself, ‘Can My Marriage Be Saved?’ She asked, instead, ‘

Should

My Marriage Be Saved?’ ”

Every morning my children and my husband leave the house, dressed and ready to spend the day outside. I am still in my nightgown, my teeth aren’t brushed yet, and I have to go back to the breakfast dishes and the house. It makes me feel terrible, as if they were people but I am not. . . . When I was a girl, I wanted to do something important. First I wanted to be an

explorer, and then a scientist. Then I got other ideas. I wanted to—it certainly seems really ridiculous now—I wanted to be a Congresswoman or Senator. Senator Barbara from Illinois, can you imagine? Me, who can’t even get dressed in the morning?

My family got worried about all my crazy ideas. After a while, I stopped having those daydreams. I went to the state university, where I met my husband, Bill. He was very smart, ambitious and powerful. I couldn’t believe he wanted to marry me. He was graduating, and he didn’t want to wait for me to finish college; three years seemed too much. So, although I was a good student, I dropped out and got married. I was nineteen years old.

Being married was fun at first, except that I didn’t know what to do with myself during the day and I was too scared to go out and get a job. My husband didn’t want me to, anyway. Then the children came along and we moved out to the suburbs, and since then it’s been, well, you know what it’s like, cooking and shopping and washing diapers and picking up kids and bringing them home and arranging everything for everybody, all that sort of thing. . . .

At home he is very demanding. For example, he doesn’t like the way laundries put starch in his shorts, so I have to iron them myself. He wants a gourmet dinner every night, so at five o’clock I make hot dogs and beans for the kids and at seven o’clock, veal

cordon bleu

with a dry white wine for me and Bill. He selects the wine, but I have to be sure it’s perfectly chilled.

We don’t have sex very often; he doesn’t seem to want it. But when he does, I know I have to make myself available. I used to want him all the time. Now I don’t feel that way anymore. These days it seems as if we either fight or don’t talk with each other at all. Last year I went to a psychiatrist. He intimated that I had hidden masculine drives. This frightened me so I never went back.