The Norm Chronicles (24 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

Although railways are generally seen as safe, people still seem to think it a good idea to spend huge amounts of money making them safer. The Rail Safety and Standards Board employed a consultant philosopher to help them understand why. He concluded that it was a moral issue – people quite reasonably had a sense of shame that train disasters could happen, felt outraged that they were caused by someone’s actions and so didn’t tolerate much risk.

7

But caution can have unintended consequences. After the 9/11 attacks in New York many people felt more nervous of flying and took to their cars instead. Gerd Gigerenzer states that 1,500 more people than usual were killed on US roads over the following year.

8

Similarly, after a train derailment at Hatfield killed 4 people in 2000, speed restrictions on the rail network while track was checked, caused the system to clog up, again people took to their cars, and it has been claimed that an extra 5 or so were killed in the first month (although it is unclear where this figure comes from). Better to stick to the train, as long as you avoid alcohol and escalators – and don’t mind pork pies or accents.

Roads

Roads are unquestionably more dangerous. In 2010 our average annual risk of dying on the roads was about 31 MicroMorts. Since the average dose of acute fatal risk from external causes is about 350 MicroMorts a year (roughly one a day, remember) this means that something like 9 per cent of that risk in the UK is on the road. Relative to trains and planes,

it is on average far more dangerous, per mile, to drive, ride a motor bike, cycle or walk wherever there is traffic.

But how many believe they’re average? Most think they’re better than that – a self-confidence known, naturally enough, as the above-average effect or illusory superiority.

9

Like everyone else, even Norm once thought he was better than average. This is illusory for obvious reasons, since only half of drivers can be in the top half, so if exactly half of drivers thought they were in the top half they could in theory

all

be wrong. Even if you’re genuinely better, you might not be much better. And if above-average driving ability turns you into an above-average jerk, you might be so cocky that you become a bigger hazard.

Illusory superiority is also linked to an illusion of control: the idea that with the wheel (or handlebars) in our grasp, our fate is in our own capable hands, not at the mercy of the pilot, who loses it and takes the plane down over a poisonous divorce. But although sitting in economy class, trapped, waiting for the wings to fall off certainly

feels

vulnerable, lack of control evidently does not equal high risk. MB had no control whatsoever during a simple heart operation. He didn’t say: ‘Let me do that.’ Even so, to be busy at the wheel with silken mastery of road and vehicle, fully in control (you think), can give false reassurance and feed self-belief. For risk on the road is clearly determined not only by our own ability but also by that of all the other drunks and lunatics out there, and partly by accidents which have nothing to do with anybody’s skill but are out-of-the-blue hazards like the stray poodle that runs out.

So again the question: are we mad? One tactic for overcoming fear of flying is to imagine you are at the controls, pulling back the joystick as you take off, like a child pretending. Clearly, we are fooling ourselves. And we know it. We are not that stupid. Perhaps what the pretence does is to remind us that at least somebody is in control, and this is what they will be doing, and we approve.

There is an argument that this double standard – the risk when I’m driving is OK, the risk on a train or plane isn’t – is justified even though it seems to reverse the statistical evidence. That argument is backed up by the Rail Safety and Standards Board’s moral philosopher: if others are in control, of course they ought to take more care of me than I might

take care of myself. That’s their job. If I risk my own neck, it’s reckless; if

they

risk my neck, it’s criminal. Hence, runs the argument, there’s logic in the ‘pages 1–12’ press coverage of a rail death – someone else is to blame, and the accident is also about public trust, corporate and government responsibility – compared with the ‘news in brief’ treatment for death on the roads, which are more like fatal DIY, a private misjudgement after which private grief is of little public importance.

You can argue with this, but while we can mock people who prefer the safety of cars to flying, some of this preference is better seen as an expression of trust, or mistrust, than proof of irrationality.

A final complication is that one response to feeling safe is to drive more dangerously. This is known as ‘risk homeostasis’, the idea that we have an inbuilt risk thermostat, a level of risk we’re prepared to tolerate (or a level of risk that we seek out and try to maintain because that’s the level we enjoy). As the risks change – with seat belts, air bags, better brakes – we adapt our behaviour to maintain the same level of risk. So, as cars are made safer, many drive faster, and transfer risk to other road users, such as pedestrians, who don’t have air bags.

According to John Adams, a specialist in transport risk, safety would be best achieved with a huge spike on the steering column pointed at the driver’s chest and no seat belt. That should recalibrate the risk thermostat of a boy racer or two to about 10 m.p.h. Dudley Moore said the best safety device was a cop in the rear-view mirror. Both in their own way argue that people become more careful the more that it hurts not to be. If you want them to drive safely, expose them to danger. The theory of risk homeostasis also works the other way: if we do protect people from the consequences of taking risks, they will take more of them. How this balance of mechanics and psychology pans out is hard to tell in advance. Will the new safety device make more difference to the casualty figures than any change in behaviour?

Adams also argues that one reason why road casualties fall is that some roads get so lethal that no pedestrian will go near them. If true, falling mortality on these roads is a measure not of safety but of danger.

In short, the risk of death or injury on the roads is subject to all manner of psychological filters and questions of interpretation. Are the data

useless, then? In fact, what they seem to say is so stark, the trends so clear, that they can stand a big margin of error or interpretation and still be clear-cut. All data are wrong. The question is whether they’re so wrong that you can’t draw conclusions from them. Here they are.

In 1950, a few years before DS was born, there were 4.4 million vehicles registered in Britain. In 2010 there were eight times as many, which after the growth of the population equals a rise from one vehicle for every 11 people to one for every 2 people.

A reasonable assumption might be that more vehicles on the roads means more deaths. Statistics suggest not. There were 5,012 fatal accidents in 1950. By 2010 this had dropped to 1,850, a fall of 63 per cent in absolute terms.

In relative terms the fall is even more extraordinary, given that there was a rapidly rising volume of traffic. For every 100,000 vehicles in 1950 there were 114 deaths. In 2010 there were 5, a 96 per cent reduction. When DS remembers how, as a child, he enjoyed riding in the front seat of their old van, which had no regular safety inspection, seat belts or air bags, and then how people used to drive to the pub, drink all evening and meander home, he is not surprised. It is a fall from an average in 1950 of 102 MMs per person per year to about 31 MMs per person per year in 2010.

Among car occupants, the number of fatalities are much as they were 60 years ago – the figure was around 20 a week in 1950, rose to 60 a week in the 1960s and now is back at 20 a week. The main saving of life has been pedestrians and cyclists: from 60 a week in 1950 (although in 1940 it was even worse, when a staggering 120 a week were killed by unlit vehicles in the black-out), down by over 82 per cent in 2010 to 11 a week. Another way of looking it this figure is that, for every 100,000 vehicles, about 1 pedestrian or cyclist is killed per year. (We will compare this with other countries later.)

These statistics depend on counting bodies, which is grim but easy. Counting accidents and injuries is trickier – what is an injury anyway, and how bad does it have to be to be recorded? – but it’s reported that in 1950 there were 167,000 accidents, with 196,000 injuries, and in 2010 almost the same: 154,000 accidents, with 207,000 injuries.

This means that people still crash into each other about 400 times

a day, but the proportion of these accidents that are fatal has dropped staggeringly, because of speed limits, safety features and improved and quicker medical care.

Almost all the richer nations have seen this trend: in the 30 years from 1980 to 2009 road fatalities fell by 55 per cent in Australia, 69 per cent in France, 63 per cent in Britain, 54 per cent in Italy and 58 per cent in Spain, in spite of increasing volumes of traffic, although the reduction in the US was only 34 per cent, and deaths actually rose slightly in Greece. For countries that collect the relevant data, we can work out an average number of MicroMorts per 1,000 kilometres a vehicle travels: 4 MM per 1,000 km in the UK, 7 MM in the USA, 10 MM in Belgium, 20 MM in Korea, 40 MM in Romania and 56 MM in Brazil.

10

But who bears this risk? In richer countries the majority of road fatalities are the occupants of cars, whereas in poorer countries it’s what are known as ‘vulnerable road users’: pedestrians, cyclists and those whole families squeezed onto a single small motor bike. In Thailand 70 per cent of all road deaths are riders of two-wheeled vehicles,

11

which will not surprise anyone who has witnessed the traffic in Bangkok.

And it’s in low- and middle-income countries that people are exposed to the serious risk. It’s estimated that around 1.4 million people are killed on the roads each year, which is around 3,500 a day, and of these 3,000 are in the developing world – in spite of those countries containing less than half of all cars.

12

The majority of these victims will be vulnerable road users. South Africa sees 15,000 killed each year, a statistic brought into sharp relief when Nelson Mandela’s great-granddaughter Zenani was killed.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) predicts that road traffic injuries will go from its current 9th position in the cause-of-death league table to 5th place by 2030, causing 2.4 million deaths (as well as between 20 and 50 million injuries), largely of young people, and at enormous cost to the economies.

13

The WHO points out that only 47 per cent of countries have laws about safety features such as speeding, drinking, seat belts, helmets and child restraints. And these are often not enforced.

The average risk for an individual from dying on the roads – 31 MicroMorts per year in the UK – is 103 MicroMorts in high-income countries

generally, but 205 in low and middle-income countries. It may seem odd that countries with fewer cars are riskier, but, perhaps surprisingly, deaths per vehicle decline strongly as roads get busier. It is empty roads that are really lethal. This observation even has a name: it is ‘Smeed’s law’ of traffic.

14

Smeed’s law is reflected in some extraordinary statistics about Ethiopia, which the WHO report as having only 244,000 registered vehicles in 2007, but which nevertheless managed to kill 2,517 people. The majority of these deaths were pedestrians – that’s 1 death per year for every 100 vehicles: the same rate applied to the UK, with 34 million vehicles, would mean 340,000 people killed each year, instead of under 2,000.

One lesson is that – if we have the money – the bigger a danger becomes through faster and heavier traffic, the more likely are we to do something to control the risks. Risk doesn’t just sit there as a settled fact of life, and it can’t be separated from how we react to it.

Flying

‘The pilot has advised that there is some turbulence ahead. Please return to your seats and fasten your belts.’

As the plane bucks around, the wings flap up and down, babies cry and the knuckles turn white, is there anyone who remains completely calm, except those who are drunk, drugged, asleep or all three?

Fear of flying, or aerophobia, is common. Around 3–5 per cent just won’t fly, around 17 per cent admit to being ‘afraid of flying’ and 30–40 per cent have moderate anxiety.

15

We have known risk professionals – archetypes of rationality – who refuse to fly.

It is a treatable condition, and British Airways runs day courses for around £250 that conclude with a 45-minute flight.

16

Sadly they do not publish their success rates, or the counts of those carried gibbering from the plane.

Again, of all the classic fear factors, it is the feeling of complete lack of control over our fate that kicks in hardest when strapped in a plane with the ground a long way off. Perhaps a lack of understanding also contributes – how does it stay up anyway? If we all stopped believing, would it fall from the sky?

And we’ve seen how the easy availability of negative images influences

our perception, and the media certainly like to linger on pictures of wrecked planes. Those of a certain age bring to mind examples from history, from Buddy Holly to the Manchester United football team.

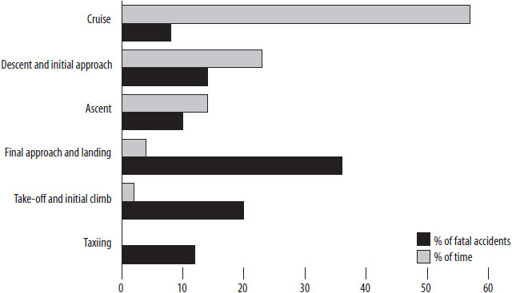

Figure 18:

How the flight-time splits, and when accidents occur, 1959–2008

18