The Norm Chronicles (25 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

But for real aero-disaster porn nothing can beat the unsubtly named Plane Crash Info website,

17

which keeps a running database of all fatal crashes involving commercial airlines, together with lurid photographs and even audio clips from the black box recorder – which are disturbing, to put it mildly. In 2011 it recorded 44 crashes, around 1 a week. Sounds bad, but it’s an improvement on 70 in 2001 (including, of course, 4 on 9/11).

Their analysis, vividly illustrated in

Figure 18

, shows that the cruising part of the flight is by far the safest, taking most time and with fewest accidents. Per minute, take-off and landing are around 60 times as dangerous as the middle of the flight. Try muttering this mantra during turbulence.

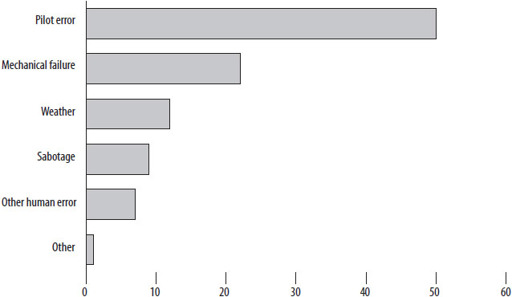

Plane Crash Info also estimates that human error accounts for over half the accidents – though whether it’s pilot error or mechanical failure, there is still nothing you can do about it.

But perhaps you can do something about which airline you fly on: Plane Crash Info estimates that, in the safest 30 airlines, there is a fatal

accident on average every 11 million flights, and since there is some chance of surviving, the odds of being killed are around 1 in 29 million per flight. In contrast, for the bottom 25 airlines, there is around 10 times the rate of fatal accidents, and your chance of being killed on a flight is about 20 times higher.

Figure 19:

Causes of fatal accidents on commercial airlines, %, 1950–2010

19

For calculating MicroMorts, the best data come from the US National Transportation Safety Board statistics on planes carrying at least 10 passengers.

20

Looking at the ten years from 2002 to 2011, each year US commercial airlines flew an average of 10 million flights. Over that period there were no major disasters, and an average of 16 passengers and crew were killed each year of the 700 million who got on a plane – this works out as 0.02 MicroMorts per flight, or an average of 50 million flights before you are killed. So if you took one flight a day, that’s 120,000 years.

Now, you may complain that we have neatly avoided 9/11, in 2001. So if we look at 1992–2011, during which there were a number of major accidents, it works out at 0.11 MicroMorts per flight, or an average of 9 million flights before you are killed.

But how should we measure these risks so that we can compare them with different ways of travelling? By journey, by mile or by hour? Let’s

use as a benchmark the somewhat pessimistic figure of a 1-in-10-million chance of being killed per flight, which is 10 flights per MicroMort. An average US commercial flight lasts 1.8 hours and travels 750 miles. So that works out as 7,500 miles or 18 hours per MicroMort, around 20 times the distance for driving in the UK, and similar to rail.

As we’ve seen, risk is not evenly spread through the flight. And if you were really going to choose transport for a trip on this basis, you would need to factor in the drive to the airport, or the cycle to the railway station and so on.

But one set of flying statistics stands out from the rest and these are a different matter: small private aircraft, known as ‘General Aviation’. There are around 220,000 registered general aviation aircraft in the US, and each year around 1,600 have accidents, about 300 of which are fatal. That’s 6 a week. On average over the last ten years, no fewer than 520 people a year were killed in small aircraft and helicopters, 97 per cent of all air fatalities.

This works out as 13 fatal accidents per 1 million hours flying, around 150 times the rate of commercial airlines. That’s around 1 MM for every 6 minutes in a small plane, travelling perhaps around 15 miles, about the same risk, per mile, as walking or cycling.

We see the same pattern in the UK: between 2000 and 2010 there were 9 fatalities on airlines, 34 in helicopters and 202 in ‘general aviation’.

21

Bigger is definitely safer. So here’s a question on the front line of stats versus psychology: do pilots of small planes feel safer for being at the controls? If you know any, ask.

One last thought. Turbulence can be dangerous even if the wings stay on: 13 people were injured during turbulence in the year up to August 2012 on US commercial airlines. Of these, 12 were cabin crew.

22

So when the seat-belt light goes on, buckle yourself in and just be pleased you are a passenger and not pushing the drinks trolley.

16

EXTREME SPORTS

I

T WAS A SLOW DRIVE

up eleven hairpin bends on the road known as the Troll’s Ladder, then a slower climb on foot following the cairns, avoiding loose rock up to the giant, conical mountain top called Bispen, ‘the Bishop’, standing like an upturned ice cream cone.

Here the air was still, clear, cold. Far below, far away, the lake was a hard spangle of light between hills and granite. High, thin clouds watched over the valley. Here the world of people disappeared. Here was nothing but the view and the drop, landscape, distant shapes and textures, shades of grey and green.

On the edge stood Kelvin, alone and scared, as scared as anyone else on the edge of a mountain. Then he stepped off.

From above, he was a wrinkle plunging to the ground. From below, he was a stick man etched against the blue. But in his own space, Kelvin had stretched out the webbed arms and legs of his flying suit against a riot of noise – and was free.

‘You just kind of go wherever you look,’ they said about base-jumping from mountains in a wing-suit, ‘just kind of … stick your arms out.’

At near-terminal velocity he planed out, swooped into a glide. On previous jumps he had ‘cleared out the space’, as they put it, got the hell out of there and flown away from the mountainside. But that got boring. He tilted his shoulders to veer towards the cliff, measuring his line past the vicious hard road of the rock face over flashing shrubs and bare

pronged trees, past jots of reflected light and sudden shadows as the land rose and fell in spikes and bumps and hollows and crevices, and beyond them all in roaring buffeting air he curved and scored the long, smooth line down.

*

Buzzing the walls, they called it, hands outstretched, a fingernail from pieces. ‘Mess up and you will 100 per cent die,’ they said. ‘Click. Like that.’ Kelvin knew it: knew it, that is, as well as any of us can know that our own death is real.

‘Sick, man, real sick,’ they’d be saying in a, like, totally envy-racked and mind-blown way as Kelvin bombed past the watching crowd on a Trollsteigen hairpin at more than 100 m.p.h., here and gone, a whistling projectile so vicious that he could smash a hole in your house but was, by the way, a human being. Cool.

For another minute he roared above forest, a flying squirrel embracing the air. Not really flying, ‘more like falling with style,’ they said. ‘The most extreme badass activity on the planet,’ they said.

And as the lake drew closer, Kelvin pulled in his arms, brought his heels together and stood up, still blazing over the water, but slowing now he pulled his cord and released the chute. And then, violently, there was peace. Only the gentle sound of Kelvin’s laughter and bottomless exhilaration, the topless high as he steered towards the shore.

And as he drifted down, he thought of those who said this was impossible. Well, guess what? He just did it. He appreciated people who thought he was crazy. He thought of Graham Greene playing Russian roulette with his father’s revolver, and some memory he scarcely recognised as his own about Dostoevsky and a piano.

‘Sick! Kelvin man!’ They said, as he walked back with his chute.

‘Dude!’

‘Sick!’

‘Yo! ‘

‘OK!’

No doubt about it: near death was real living.

THERE IS A BIANNUAL

competition for jumping off cliffs in a wing suit. It is, incredibly, a race. The aim is to be fastest down. It is called the Base Race and is organised by the perfectly named (for a risk-taker) Paul Fortun from Germany. You’d think, unlike Kelvin, he’d be fearless. How else could he step off a mountain? But in 2012 he said: ‘I’m terrified every time I jump, everyone is. I think if you’re not scared of something like this, then why bother?’

2

Which is a neat inversion of the precautionary principle – do it

because

it might go wrong. ‘It’s all about the taste of fear and lack of control,’ he said. ‘I love it.’

Much of this book discusses mortal danger as if it’s a bad thing. But danger can be a scream. Oddly, those who love it and those who hate the idea needn’t necessarily disagree about the quantified risks. Paul Fortun and Kelvin do it not because their perception of the probability of death is different from other people’s, but because it’s much the same. That’s why they like it.

*

Even when life was brutish and short, with daily risk from disease, hunger and conflict, and you might guess that not many would choose to stand, or jump, sportingly in harm’s way – there being quite enough harm around already – people boxed bare-knuckle from the early 16th century, played or more accurately fought in the kind of mass football slugfest without referee or rules that occasionally left people dead and maimed, or, if rich, they jousted (in medieval times) and (later) galloped full-tilt over hedges.

As life became more cosy and predictable for some of the richer citizens of 19th-century Europe, there was the Alpine Club – membership criterion: ‘a reasonable number of respectable peaks’ – founded in London in 1857, when the British dominated mountaineering and bagged the classics in desperately unsuitable clothing. These gentlemen – and one or two women – had many motivations. For some it was science, for others a spiritual union with nature, for a few ‘the cool keen finger of danger’.

3

Climbing mountains was risky then and can still be risky now. Apart from the possibility of falls, there is low oxygen, freezing temperatures, exposure to wind and sun, and exertion. But it’s difficult to put numbers on these risks. For although it is relatively straightforward to count dead bodies, do we consider these deaths as a proportion of all who go climbing, or of only those who attempt high peaks per day of activity? Another problem is that, whatever the measure, we need to know how many people get up to whatever it is that turns them on, and these data can be hard to find. So the following numbers are bound to be rough and ready.

By the end of 2011, 219 people were known to have died climbing Mount Everest, 1 for every 25 who reached the summit. Of the 20,000 mountaineers thought to be climbing above 8,000 metres in the Himalaya between 1990 and 2006, it was estimated that 238 died, a rate of around 12,000 MicroMorts per climb.

4

In another study of 533 mountaineers on British expeditions above 7,000 metres between 1968 and 1987, there were 23 deaths (1 in 23), equal to about 43,000 MicroMorts per climb.

5

Mountaineering at these levels is riskier than a bombing mission in the Second World War, or about equal to 117 years of average acute risk.

Next, falling with style. For while some are terrified at the thought of stepping into an aeroplane, others enjoy stepping out mid-flight, or otherwise hurling themselves into the air. The dangers have been apparent since Icarus first strapped on fake wings and discovered that the birds had made it look too easy.

Parachutes were developed in the late 1700s, hang-gliders a hundred years later. This was a time when inventors were expected to demonstrate their bolder ideas personally. One such was Franz Reichelt, in 1912. He was a tailor who invented a wearable parachute, like a cross between a voluminous raincoat and an inflatable dinghy. It worked with dummies.

He assured the authorities that it was a dummy he wanted to test at the Eiffel Tower. At the last moment he clambered on top of the railings wearing the parachute and could not be dissuaded. Early film shows the heart-stopping moments as he rocks back and forth, finding the courage to jump, then flutters forlornly down like a shot bird. The crowd,

silent in the film but doubtless screaming, rush forward to see his body on the frozen gravel.

6

The police are then seen measuring the depth of the dents.

Parachuting competitions began in the 1930s, and the US Parachute Association estimated that an average of 2.6 million jumps were made each year between 2000 and 2010.

7

But it’s still not entirely without risk: in that period 279 people died, around 25 a year for a rate of about 10 MicroMorts per jump. Examination of the details of the accidents reveals these were mainly experienced enthusiasts with thousands of jumps behind them, pushing things a bit far. Novices were safer.

Reichelt could be considered one of the first base-jumpers, a sport in which sky-divers leap from fixed objects rather than planes. This, it hardly needs saying, is dangerous, although, perhaps surprisingly, it can be less dangerous to jump from certain mountains than to climb an especially tall one. The Kjerag Massif in Norway is one of the safer launch points, with a sheer 1,000-metre drop. In theory, this allows ample time to do something to soften that inevitable reunion with the ground. Nevertheless, over 11 years and 20,850 jumps, there were 9 deaths and 82 non-fatal accidents

8

: that’s one death in every 2,300 jumps, or an average of around 430 MicroMorts per jump. And this is one of the safer spots: base-jumping is not a mass-participation sport, for obvious reasons, but 180 deaths have been recorded, increasingly featuring wing-suits that open up like a flying squirrel, much as poor Reichelt originally intended.