The Norm Chronicles (3 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

‘Erm, the fish …,’ he said.

‘Yeah, the fish,’ she said.

‘Dead?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Right. I kinda knew that. I think it was me.’

‘Uh huh.’

‘So, erm, how much is a fish?’

‘For one fish? … dinner.’

‘What? … dinner?… Oh, OK! Yeah, dinner. But like, not like … not for every fish?’

‘Hey, come on, fish killer!’

‘OK, OK …’

‘Though to be honest … they weren’t my fish. But it’s either dinner or I tell my brother it was you and as he’s a psychotic axe murderer. You don’t want that.’

‘Right. Sure. So … how many fish?’

‘Forty-two.’

‘Forty …?!’

And had they not then discovered a shared love of Sudoku, sailing and an original sound recording of Alfred Tennyson’s ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’, plus that he really liked her smile and she liked his hands and had a fascination for the strange birthmark on his right ear, well …

‘Incredible,’ they often said afterwards.

‘What are the odds against meeting like that?’

‘But “forty-two”! It wasn’t even true.’

‘Exactly!’

So it was only after a heap of happenstance, a whole cocktail of accidental, it-could-all-so-easily-have-been-different events that they met again and talked and fell in love and had a baby – after he forgot the contraception the time they went camping but said ‘What the hell’ anyway – which really should have made the whole saga about a zillion to one against.

But then, when you think about it, everyone is improbable, everyone’s story’s a fluke. There are so many reasons why any one of us might not have happened. At least, every particular someone is improbable. There’ll be people for sure, but why you?

As it was, by going back to say sorry, he was out when his flat caught fire and filled with suffocating fumes.

So as she lay screaming for an epidural and swearing that he was going to pay for this with his ass, was going to sleep with the fishes in fact, he was wondering about the baby’s future, the strange course of luck and bad luck, the risks and coincidences of life, wondering how much in the riot of fates was calculable. What

are

the chances?

And at the very moment the baby was born, far away a spectacular fireball lit up the pre-dawn sky, a radiant explosion caused by the atmospheric entry of a small near-Earth asteroid just a few metres in diameter but weighing 80 tonnes and firing icily through 12 km of space per second, such that it shattered with the force of a thousand tonnes of dynamite and the brightness of a full moon into small meteorite fragments across the Nubian desert below.

1

The asteroid was named

Almahata Sitta. The baby was precisely 3,400 grams.

*

They named him … Norm.

CAN NUMBERS HELP

the infant Norm duck the slings and arrows of life? In

The Norm Chronicles

we will guide him with the best that we can find. We will also make them as clear as possible.

The last point – clarity – is a big one. There are lies and damned lies in risk statistics, for sure, but there’s real information too, and a large part of the problem is cutting through to the good stuff and making it intelligible.

Say that Norm’s dad is cooking sausages for the boy’s tea when his ears prick up to a headline on the TV news that says eating an extra sausage – or is it a sausage every day? – something about a sausage anyway – increases our risk of cancer by 20 per cent. He pauses. Norm plays. The sausages sizzle.

†

What does it mean, this percentage – 20 per cent more risky than what? Then he hears it referred to on the radio as a probability (and is that the same as a percentage?), and maybe later he’ll read in the newspaper about the ‘absolute risk’ and a ‘relative risk’, and by now he’s struggling, and who can blame him? But then there’s another thing they talk about, called a ‘risk ratio’, and it all seems mathematical and maybe even rigorous – who knows? – and so some say ‘you mean 20 per cent of people die from sausages?’ and others ‘you mean extra sausages cause 20 per cent of cancers?’ or perhaps ‘you mean 20 per cent of people have a 100 per cent chance of cancer if they eat, er, 20 per cent more sausages?’ And some, who love sausages, say that it’s all lies and statistics, but perhaps a few say, ‘Oh my God, it’s a sausage, stay away!’ and they hardly believe it, but maybe they should believe it, and some people tell them they’re just stupid, but they don’t feel stupid they feel fed up, and still they haven’t much idea what it really means, and in the end they say ‘Oh, sod it, let’s have another sausage.’

Forget all this. We can do better. Norm faces a life full of such fears, often conveyed with about as much clarity. Can we ever calculate his precise fate? No. Obviously. No one knows the future. But as Norm grows up he can learn about the recent past – as with the body count for heart disease – and then extrapolate the average risk into the future and use this as a guide for his own life. This sounds imperfect but reasonable. In practice, risk in the telling is often a mess. Yet so far as the basic body count goes and what it means to our everyday lives, it could be easier. That, at least, is one hope for this book, and for Norm too. Although danger isn’t only something people fear and avoid, and maybe even sausages taste better if you think they’re on the wild side. Either way, whether you seek danger or avoid it, we will try to make the numbers simple.

Our main technique will be a cunning little device called – by someone

3

with a wicked sense of humour – a MicroMort, which is a 1-in-a-million chance of death. MicroMorts are cheery little units that help us see danger in terms of daily life. They are risks reduced to a micro or daily rate on a consistent scale. The idea starts with exactly that: an ordinary day in the life of any average person, like Norm.

How risky is it for Norm, or for you maybe, to get up, go about your daily routine, do nothing particularly dangerous – no wing-suit flying or front-line duty in Afghanistan, just the ordinary – then come home and go to sleep? Not very, as you would expect.

True, you might lose your life under a bus rather than just your ice cream, slip fatally in the bath or be murdered in a mistaken gangland revenge attack with a power tool, but it’s not likely. It is a pretty micro risk. We know this. In fact, we can count the bodies and put a number on it. Typically, about 50 people in England and Wales die accidentally or violently each day by what are known as external causes.

4

*

Since there

are roughly 50 million people in England and Wales, this means that about one in a million gets it this way, every day. Not a lot, as we said. And even though you don’t know for sure if you will be one of today’s 50 or so who die from external causes, you’re probably not lying awake worrying about it too much.

So this daily risk is about 1 MicroMort, a one-in-a-million chance of something horribly and fatally dramatic happening to Mr or Ms Average on an average day spent doing their average, everyday stuff. One MicroMort, in other words, is a benchmark for living normally. You have experienced this, often. What’s more you survived. Congratulations. There you go, one MicroMort, today, tomorrow, every time.

Of course, this is just an average, and who except Norm is average? Some people are too timid to step out of the front door, while their neighbour revs the motor bike on the way to a base-jump. What

Your

risk is (that’s You reading now), is a much trickier question that we will come to later. For the moment, please imagine Yourself to be average.

We will also have to assume that recent data give a reasonable idea of the future. In other words, we will move smoothly between historical

rates –

how many people died out of each 1 million? – and future average

risks

– what is the average number of MicroMorts per person? But by ‘future’ we only mean the next few years – who knows what will happen after that?

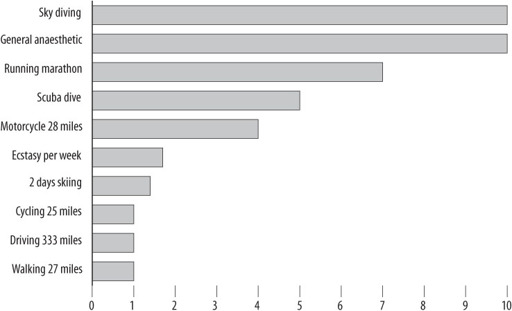

With MicroMorts at the ready, the rest becomes relatively easy. How will you spend your daily MicroMort (MM)? If you ride a bike for 25 miles, that’s your daily ration. Or you can achieve the same by driving 300 miles, also equal to 1 MM (remember this is an average – 1 MM goes further on motorways). Or you can take a few more risks and add to your daily MM dose.

The joy of the MicroMort – if joy is the word – is that it makes all kinds of risks comparable on the same simple scale. And there are plenty of risks about. For instance, have you in the past ever been born? Do you expect to give birth? Do you now or will you ever drive or fly? Take drugs,

including alcohol or painkillers? Ride a horse or bike? Climb Everest? Work down a mine? Climb a ladder? Spend a night in hospital? Have you or your children ever had a jab? Do your toddlers put small plastic toys in their mouths in flagrant violation of the clear written warning on the packet? What’s the risk that an asteroid is right on target for you?

All of these, and every other acute risk can be measured in MicroMorts (MMs). For example, the risk of death from a general anaesthetic in a non-emergency operation in the UK is roughly 1 in 100,000,

5

meaning that in every 100,000 operations someone dies from the anaesthetic alone. This risk is not as intuitively easy to grasp or compare as it could be. But we can convert it into 10 MM, or 10 times the ordinary average risk of getting through the day without a violent or accidental death, or around 70 miles on a motor bike. We can show you, for example, that every two shifts working down a mine not so long ago in the UK was, on average, about the same risk as going sky-diving once today: about 10 MM. A day skiing? An extra 1 MM, the same as an extra average day of nothing much. Anna would be reassured.

But at the extremes, one MicroMort is also the average risk incurred every half-hour serving in the armed forces in Afghanistan in a bad period, 48 times more dangerous than average everyday living. Or it is the risk incurred by the aircrew of a Second World War RAF bombing mission over Germany in around one second.

*

A MicroMort can also be compared to a form of imaginary Russian roulette in which 20 coins are thrown in the air: if they all come down heads, the subject is executed.

†

That is about the same odds as the 1-in-a-million chance that we describe as the average everyday dose of acute fatal risk.

Figure 1:

Some MicroMorts

Average MicroMorts (1-in-a-million chance of death)

See

Figure 36

in

Chapter 27

(p. 292) for lots more and details of how they’re done and where they’re from.

While we’re on the subject, take a moment to decide whether you would be willing to play this game of being executed if 20 coins all come up heads and if we paid you, say, £2 a go.

You wouldn’t? £2 is not enough, you say. So how much money would you want in return for accepting a 1-in-a-million risk to your life? In other words, how much is your life, or a 1-in-a-million threat to it, worth?

We can form an idea of how much governments are prepared to pay to save you from a MicroMort by looking at the Value Of a Statistical Life (known in the trade as a VOSL). This is a real-world concept used by governments to determine, for example, which road improvements to make. If a new junction is expected to save one life, then in the UK we will pay up to £1.6 million for it.

7

Therefore the government prices a MicroMort at one millionth of this, or £1.60. Were you willing to play the Russian roulette game for £2? No? The government thinks you’re over-stating your value.

We will present risks in a variety of ways, but we will use MicroMorts often. The MicroMort describes acute risks, those that hit you over the

head with a ‘Thank you and goodnight’. Later, we will introduce another measure, the MicroLife, to talk about longer-term hazards: chronic risks of the kind that slip slowly into the bloodstream and build up over a lifetime, such as cigarettes, diet and drink.

Both measures take a few liberties and make some sacrifice of precision in exchange for ease of use as a daily measure of the hazards of life: one number, easy to compare with every other, rather than a muddle of percentages. Sometimes we will show the calculations involved, but we will tend to put these in the notes for those who want to skip them.

It is partly on the sense of proportion from MicroMorts and Micro-Lives that Norm will eventually stake his hopes for a fulfilled life, in which knowledge and comparison will guide him, help him realise his full potential to become the flourishing, uninhibited Norm he was always meant to be. So far, so reasonable – if reason is what counts. In time, we’ll see. First, there’s someone else we’d like you to meet.

2

INFANCY

F

ROM THE DAY PRUDENCE WAS BORN

, her mother was never not afraid.

*

She became protector, haven, she-wolf, sniffing danger like a forest animal. Other children were germy, snotty, clumsy, other. Fungus and barbed wire, on legs.