The Norm Chronicles (6 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

These were horrifying cases. Our problem is that horrifying cases distort our sense of the odds. Precisely because they are rare, these events stand out. The word ‘salient’ describes risks that catch the eye. In this context, salience means something like the way a light seems dim or bright depending on its background. So one appalling example now and then against a background of low odds stands out more than if the danger is common. It is a troubling trade-off: just as we pay for trying to avoid the worst with being reminded of it, so we pay for rarity with sensitivity.

So is it despite or because of the fact that the chance of violence to young children is so remote, that parents have grown – according to some writers – more anxious about their children’s safety?

*

The salience paradox is one putative explanation for this split between low odds and high anxiety. The safer life becomes, the more terrible seem the extreme exceptions.

†

A question for everyone is whether this gap between the odds on disaster and how anxious we are proves we’re paranoid and irrational, or that the data miss the point, or both. To the rationalist who says: ‘But don’t you realise how rare these things are?’ there is, for some, a paradoxical answer: ‘Yes, which is why they are so alarming.’

Here are some of the numbers. The risk of homicide is lower for children aged under 15 than for any other age group, at between about

2 and 5 MicroMorts every year. So it takes a year before a child is exposed to a murder risk equivalent even to the normal hazard of acute death from non-natural causes that an average adult is exposed to every few days.

2

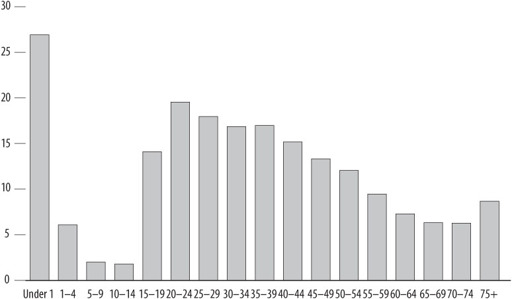

Figure 4:

The annual chance of being murdered, by age, in MicroMorts (averaged over the three years, 2008–11), England and Wales

That’s children. For infants, it’s a somewhat different story. Those aged under one are more likely to be murdered than any other age group. But the risk is still low compared with the daily hazard of average living. At about 26 MicroMorts a year, or about 0.07 MM a day, it is roughly one-fifteenth of the adult baseline everyday risk of death from all non-natural causes of 1 MM a day.

But still, as Pru’s mother says, it happens: about 46 child murders a year (on average), out of around 10 million children under 15. A more homely, more human and more sinister way of describing how often children are murdered in the UK is about once a week.

But if you can rule out murdering your own children, you cut out about three-quarters of the average risk for all under-15s, which all but wipes it out for most children in this graphic, and reduces the murder risk for under-1s from 26 MMs to about 5, lower than for almost all adults. And yet still it will not be zero.

Trends are harder to spot. Disregard what you read to the contrary,

*

the numbers are so low and prone to fluctuation that it is hard to say with any confidence that there is much of a child homicide trend at all in recent decades, one way or another.

4

For abduction, the chances are higher. But a study in 2004 found, as with homicide, that children were most likely to be abducted by their parents (141 cases, about 90 per cent of them successful).

5

Many of these were by partners, sometimes from different racial or ethnic backgrounds, disputing the custody of their children.

According to the study, strangers attempted many more abductions but were far less successful (364 attempts, 67 successes). The motives of strangers are usually assumed to be sexual. For these cases, short of murder, the same study said that ‘in all offences where information was available the abducted child was recovered within 24 hours of being taken’.

Homicide and abduction count only the worst of what happened. But the difference between what does happen and what might is one of the ways in which risk calculations seem to some people to miss the point.

The figures count actual abductions or obvious attempts, not malicious intent or vulnerability. So let’s try to capture the sense of potential risk rather than only the real incidents, and count all the cases of missing children – as just one among many possible ways of measuring vulnerability.

Now the numbers explode. In 2009/10, according to the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre, there were an estimated 230,000 ‘missing person incidents’ for children under 18.

6

But again, most return within 24 or 48 hours, more than two-thirds seem to go missing because they decide to, and the incident count can include the same person who goes missing more than once.

Even so, as the report says:

When a child goes missing, there is something wrong, often quite seriously, in that child’s life … Abuse, exploitation, and risk to life are the most concerning of all dangers that children face. Other risks include violence, criminality, and loss of potential due to lack of school attendance or other education, lack of economic wellbeing, sleeping rough, hunger, thirst, fear and loneliness.

But why count only missing children? Some would count all children everywhere for the measure of who

might

fall victim.

Part of our anxiety is who might be out there with a vile motive. Until these people commit an offence, that is hard to know. Afterwards, the authorities try to track all offenders who are not in prison. Since some are tracked for many years, even for life, the total number like this has risen relentlessly since the tracking came in a few years ago. That does not imply a growing threat; it simply reflects the fact that we have only just started counting and the numbers are adding up. Not all these tracked offenders have offended against children, but those who have and are still considered a risk are included with others in the table reproduced below, under what are known as multi-agency public protection arrangements (MAPPA).

*

In 2010 there were more than 50,000 offenders tracked and managed by MAPPA, which sounds truly alarming. The number at the most serious level of sexual risk was 93. (These are known as Level-3 offenders, the toughest to deal with and control, including those who hit the news.)

And supervision doesn’t always mean prevention. More than 1,000

offenders of all types were returned to custody for a breach of licence or of a sexual offences prevention order, and 134 MAPPA-eligible offenders were charged with a Serious Further Offence. Again, for many people the simple presence, out there, somewhere, of anyone who has a history of harming children is enough, and the vagueness of the threat – you don’t know what they might do or who they are – only makes it worse.

Some parents are not that worried. Some worry only in crowds. Some can’t bear to let their children play outside. Some worry only when a crime hits the news.

And some say it’s all a ‘moral panic’. The phrase was popularised in the 1970s in an analysis of the Mods and Rockers of the ’60s written by a sociologist, Stanley Cohen.

8

In brief, the argument is that the media overreact to behaviour that challenges social norms, and this overreaction comes to define the problem, even creates a model for others to copy. It is a powerful analysis. But the word ‘panic’ suggests irrationality, as if you are a parent, and you see another parent lose a child to a violent stranger, and your heart screams, but you must not pull your own children closer. Is that reasonable? Or is it the case that nothing can tell us when proportionate reaction ends and overreaction starts? There is no tape measure – in MicroMorts or otherwise – for the shock of a child violently killed. Was the shock disproportionate in December 2012, when 20 children were murdered by a gunman at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut? Does that shock change if you know that there are roughly 15,000 homicides in the US each year?

4

NOTHING

T

HE BIG SAUCEPAN

on the hob with water in made funny plopping noises. Steam hissed out. The egg inside rattled. The blue fire underneath was jumping. Prudence went to see.

Usually, mummy didn’t let her – and turned the handle away. She’d be next to you if you did something naughty and she said it was dangerous.

‘Prudence, are you there?’

She’d say, ‘No’ (before the scalds, the shrieks, the inconsolable pain).

‘Prudence? Don’t wander off, love.’

Today the little girl wanted to pick up the saucepan like mummy picked up saucepans, and she went to the gas and the bubbles, nearer, and she reached for the handle, and mummy came in, picked her up and turned it off.

‘There you are! And it’s ready.’

Meanwhile, six-year-old Norm was sulking.

‘I can’t find it!’

His father turned around in the driver’s seat. The lights changed. The car behind hooted. He jolted back in his seat and glowered in the mirror, thought about sticking a raised finger through the window, as seemed to be the fashion nowadays, then thought better of it and pulled away. But Norm was convinced they’d left it behind.

‘It’s not here!’

His father turned again to reach back and rummage in the pile on

the seat, then change a gear, turn again, glimpse and accelerate.

You couldn’t blame the driver of the Waitrose lorry coming in the other direction. He had no chance. He scarcely touched the brakes as Norm and his dad veered over. In one awful moment the cab of the HGV loomed and filled the windscreen and Norm’s dad popped the wheel over to get out of the way and pulled into the bus stop to look for Norm’s Sudoku properly.

‘Be careful, Prudence, you might fall.’

‘But I might not.’

At home, Kelvin lit a match and dropped it into the ashtray on the kitchen worktop. He watched as a wicked flame got the napkin, but then caught a corner of kitchen roll that was near, then the tea towel. The fire was growing. Kelvin stepped back. He didn’t mean that. What had he done? Before his parents in the living-room could separate the smell of their own cigarettes from real smoke, fire had taken the curtains and Kelvin was staring at a sheet of flame. His dad raced into the kitchen to find that pretty much everything flammable had gone up – there wasn’t much – and the fire had petered out.

By evening, Prudence’s mother stood in the doorway, arms folded, eyeing her husband sprawled on the sofa in front of

Newsnight

. Useless, waste of space he was, her best kitchen knife lying ruined on the coffee table where he’d left it after changing a fuse on a plug because he couldn’t be bothered to go out to the garage for a screwdriver. Look at him. Useless, always in the way, with not an interesting word to say, and what could she have seen in him? And ten years of resentments poured through her. Thirty more of ghastly married solitude reared up. And she stared at the knife and felt a despair that flared into a rage so sudden that in one swift movement she strode over and took the knife and felt the strength of vengeance in her right arm for all her murdered hopes as she saw the terror in his pleading little eyes and raised her hand and plunged the knife deep into his chest in one of those trivial fantasies of resentment that came and went in a blink before she sighed and smiled, and went over to pat his head.

‘Ready for bed, love?’ she said.

IN A COMEDY SKETCH

by David Mitchell and Robert Webb, a film-maker (Mitchell) is interviewed about his

oeuvre

after a clip from his latest work:

Sometimes Fires Go Out.

In the film, as a couple watch TV, a small fire in the kitchen– yep, you got it – goes out. That’s it.

The interviewer (Webb) says the film has been reviewed as ‘unrelentingly real’, ‘a devastatingly faithful rendition of how life is’ and ‘dull, dull, unbearably dull’ – all those comments, oddly, from the same review.

He introduces a clip from another film:

The Man Who Had a Cough and It’s Just a Cough and He’s Fine

.

Two Edwardian lovers have a series of rendezvous on a station platform. The man, spluttering, looks more pallid and doomed with each encounter. ‘It’s just a cough,’ he says, stoically.

Except that it is. It’s just a cough. In the last scene he’s dandy. It is one of the finest comic sketches about probability you’ll ever see. But then, where’s the competition? The idea is lovingly ripped off in our fiction, with some added examples.

Explaining jokes is a bad idea, and the joke here is simple: stories are about what happens; they’re not often about what doesn’t. If nothing happens in a story, it is not usually a story, it’s a joke. And that, funnily enough, is a problem.

Fictional stories choose what to bring to our attention, or their authors do, and whatever they choose, they choose for a reason, often to prime the reader for what comes next. Anton Chekhov said: ‘If in Act I you have a pistol hanging on the wall, then it must fire in the last act.’ Or imagine an episode of the hospital drama

Casualty

, the family gathered around the breakfast table, when the old man coughs …