The Norm Chronicles (5 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

The admirable UN Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation

8

puts all these data together and estimates that, over the whole world, the average risk faced by a baby in the first year is around 40 per 1,000 (a chilling 40,000 MicroMorts), about the level in England and Wales in 1947.

But, like so many averages, this obscures massive variation. Bottom of the league table are Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of Congo, with rates of around 119 and 112 per 1,000 respectively, the English rate in about 1919. Ethiopia comes in at 52 (the English rate in 1938), India 47 (1945), Vietnam 17 (1973), with the USA at 6 (1997). Cuba’s 5 per 1,000 is a fraction behind England, while Finland and Singapore are down to 2 per 1,000,

9

about half the rate of the UK. This suggests that we cannot separate the world into ‘us’ and ‘them’ – ‘they’ are mostly like us a generation or so ago, and catching up fast.

*

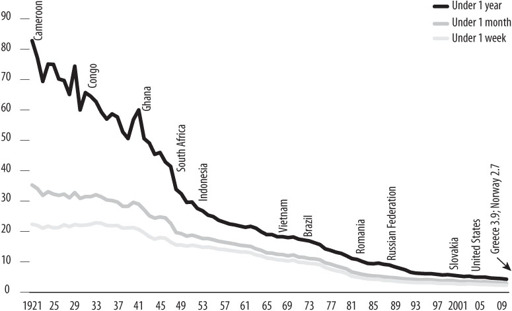

The line in

Figure 3

shows the dramatic improvement in the UK’s infant mortality rate since 1921, measured in deaths per 1,000 live births before one year old. We’ve also shown the current position of a selection of other countries. Thus Cameroon in 2010 was about where the UK was in the early 1920s.

Figure 3:

Infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births, UK historical trend, with current position of selected countries

10

The Millennium Development Goals were set up by the United Nations in 2000, and the fourth goal was to reduce infant mortality by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015, from 61 per 1,000 live births to 20. The current level of 40 shows great progress over twenty years, but means the overall goal is unlikely to be met, although some countries have made giant strides: for example, Malawi has gone from 131 to 58 per 1,000, and Madagascar from 97 to 43, both of which are 56 per cent reductions in twenty years.

11

If you have the impression that the developing world makes little progress in human welfare, think again. The number of babies who died before their first birthday is estimated to have fallen from 8,400,000 in 1990 to 5,400,000 in 2010 – an astonishing improvement but still 15,000 a day, 600 an hour, 10 a minute, 1 every six seconds.

Here’s an odd question: is the death of a baby just nature’s way, as Prudence’s mother fears, or is it unnatural? The distinction matters. Many people feel that unnatural risks – risks associated with modern living, such as travel, technology or obesity – are worse. Humans created them because enough of us liked the benefits from cars, nuclear power or cakes. But if what we create also messes with nature, well, some say, what

do we expect except our comeuppance? Better to go by a lightning strike than a downed power line, as one piece of research put it.

12

Maybe these unnatural risks feel worse because this is what happens when humans get above themselves, or maybe they feel worse because someone else imposed them on us. In contrast, we might call the death of a very small child more like supreme bad luck, an act of God or nature, primitive or given, especially when illness is the cause.

‘Natural’ risks are often more tolerated. But it’s an awkward attitude, and this chapter tests it to the limit. For what greater fear is there than that of seeing your child die? The narrative is so disturbing that even TV uses it sparingly, while portraying adult death on an industrial scale.

Disease is natural and slaughters people in the millions. Should we tolerate it because it’s always been around? And yet ‘unnatural’ remains a potent criticism, even though humans brought a dramatic decline to the natural rate of infant mortality, sometimes with nothing more unnatural than germ theory and soap. Few people think we should not have messed with it.

Although the anti-nature argument can be taken too far: does it mean technology is always good? Obviously not, even for children’s health. Neither side wins every time. The natural/unnatural risk argument rumbles on around home birth (and vaccination – see

Chapter 6

).

Is this odd preference for natural risks irrational, when natural risks can be the most devastating of all? Strangely, maybe not. ‘Unnatural’ can be a way of saying that you don’t like a risk for other reasons. Maybe what you mean is that an unnatural risk is when people or big business get up to no good. Maybe you think someone is making too much money or seeking too much power. ‘Natural’ and ‘unnatural’ might be bound up with tricky ethical or moral feelings about the way a whole society behaves, nothing to do with hard and fast distinctions in nature itself. This doesn’t make these feelings irrational, but it does make them complicated. Risk is often like that: ostensibly about danger, but really packing a whole lot of attitude about a whole lot more.

From thinking of one child, our own, and trying to imagine the loss, to thinking about the same loss multiplied more than 5 million times every year, then of another 3 million who now survive thanks to

economic development, technological progress and the medical control of disease, seems to leave little room for sentiment about risk and nature. But the sentiment persists. What does that say about us?

That risk, even a risk like this, is a small part of a sprawling human calculation about what’s right and how to make progress, a calculation that’s sometimes political, sometimes moral and sometimes, possibly, simple vanity.

3

VIOLENCE

H

ARRY THE HAWK’S

gimlet eyes policed the city’s criss-cross streets on behalf of pest control division – ‘Rat-Swat’ – of the municipal department of environmental health. High above, he twitched his feathered wings and rode the air, watching.

People, about their business. Vehicles, moving and stopping. Trees in the breeze. Children in danger.

There by the park, for instance, walked nerdy Phil, now in long trousers, not far from the older lads hanging out in the park. Phil stopped to stare at a puddle. The puddle fizzed. From beneath the broken words ‘Central Electricity Board’ on a half-sunk and vandalised iron cover came pops and flashes.

‘Idiots,’ said Phil, a tad too loud as he stepped around the water. ‘They’ve actually electrified the pavement!’ Harry saw the lads walk over. There was shouting, a scuffle, a knife. Phil fell – with a splash.

Across the street, Harry could see Mikey leaning on the railings. Mikey had been there a good 15 minutes, had made the call on his Blackberry to report the puddle shortly before a stranger’s hand scooped up the small rucksack with his laptop, GCSE textbooks and notes that he left leaning against the post-box.

‘Why is he wriggling in a puddle?’ said Norm, who was nearly three and a bit, as he stopped beside Mikey, who had turned away from the railings and was now crouched and hiding behind the post-box tapping

the phone again and not answering him and saying a word Norm thought might be not a very nice word.

‘Are you hiding?’ Norm said.

He was a bit frightened before, when daddy went and didn’t come back somewhere and told him to stay here but he couldn’t remember where here was. Now it was cold. And the man with the phone looked at him in a funny way. Norm wondered if he was a stranger.

‘Because we don’t want him getting a chill,’ said Mrs Assabian, just along from the puddle at number 38, as she wrapped Artemis in his Dolce & Gabbana fleece jacket and tightened the buckles under his little tummy. ‘Now go,’ she said to her nine-year-old daughter Jemima, whose other bruises had largely healed, ‘or you’ll get another’ and clipped on the lead while shoving them down the steps, turning back inside and closing the door.

Harry registered in fine detail the movement of these two small figures, one upright, one horizontal. Horizontal had four legs. This was important. It scuttled from left to right, intermittently jerking forward, a pattern Harry recognised by instinct, honed by reward. He watched. Then he swooped.

Bloody big rodent, thought Harry, as he sank his talons into the red coat with the strange markings and began to haul the vermin aloft. But the vermin was stuck. Harry flapped harder.

Mrs Assabian’s daughter, by now in the High Street at the window of a shoe shop, felt her right arm wrenched to the left behind her then yanked into the air. Twisting, she met Artemis at eye level, his paws dangling, snared in the claws of a beast beating the air.

‘Noooo!’ she screamed, ‘Get off, get off!’

She pulled and screeched, fighting as she had learned to fight other blows. Harry screeched too, louder, and flapped harder. A male passer-by spotting a once-in-a-lifetime chance of tug-of-war for an airborne chihuahua, joined in, laid a hand ineffectually on the leash and absolutely screeched.

Shoppers turned – and screeched. Artemis screeched, as best 3 lb. of dog can, and then, with a rip, fell to earth. Harry flapped away, towards the river.

Where the crescendo of screeches carries the short distance over the city to find the four-year-old Prudence in the car seat as her mother drives them home from a trip to the big city. The traffic noise surges around them. Mummy hoots the hooter. From somewhere behind them, another hooter blares, livid and too long.

‘What’s that, mummy?’

‘Silly man.’

A small van behind them whines up through its gears. The van is veering and tilting insanely across the lanes. It squeals and stops in front of them. They brake hard, inches shy of a crash, and the horn blares again.

Blind to the traffic that checks and veers around his van, Van flings open the door and jumps out, engine running. She tries to pull away, but they lurch and stall. Head down, she twists at the key, pulls the wheel hard left, lurches, stalls again, twists, starts, revs high in panic.

Too late. Van has swept around his bonnet and as they begin to drive, leaps at the side of the car, clinging to the rim of the roof with one hand, feet unseen wherever they can hold.

Tongue out and leering, but silent, Van’s face is pressed to the driver’s-side window, his other hand a fist, beating at glass, door, windscreen. She accelerates. Van is still there, a limpet, an alien, a beating fist. He has to jump. He must. He holds on. Still he holds on, then jumps backwards – and spins onto the road.

It has taken just seconds. Not a word, not a shout, plumes of breath in the cold, Van saunters to his van, settles in as he moves off, reaches for the still-open door as it waves out against the turn of the van, pulls it shut and drives off.

Prudence is silent. So is her mother, staring straight ahead as she grips the wheel. Never complain, never look, never speak out, keep away, strangers, mayhem, accident, danger, madness, hatred, death.

High above, Harry circles.

They drive home. In the column asking if the parent gives permission for the school day trip, Prudence’s mother circles ‘I do not’.

FOR A PRICE

, Norm’s parents could have his genomic DNA isolated and quantified using agarase gel electrophoresis, in which ‘a region of

gDNA is selectively amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)’ for a home DNA storage kit.

Why? In case he gets lost – as he does. You could do the same for your own children. At least, that’s the most innocent motive. The darker thought, the thought of what DNA is used for, is to detect crime. And that means abduction, or worse. The sooner the police have these DNA details the better, say the instructions on the tin. You can also have your child’s tooth-print recorded on an arch-shaped thermoplastic wafer. Let’s not dwell on the moment that comes in handy. Fingerprints, identity bracelets and recent photos are often recommended.

Abduction is a scary thought. Does this kit make it any better? Would you feel happier for Norm knowing that we had his DNA in a tin? That’s the problem with fear, a cruel, insidious thing: finding ways to alleviate it means thinking about it.

Could we ignore it instead? The chance that a stranger will try to abduct Norm or any other young child is on average extremely small; the chance that the stranger will succeed is 80 per cent lower than that. The chance that someone will murder your child is smaller again; for murder by a stranger, even that risk is cut by about another three-quarters. If you are a parent, by far the biggest violent risk to your child, on average, is you.

Even including the risk from parents, the risk of death from all causes for young children like Norm is the lowest it has ever been, and this is also, as we saw in the last chapter, the age of lowest risk in an average human lifetime. That is, based on the most recent data, early childhood is the safest age to be alive, at probably its safest moment in history.

So what? Bad things happen, as Pru’s mother says – and she is right. Our fiction is an absurd batch of shocking dangers and calamities – deliberately so – especially in the space of a few minutes and a half-mile radius. But they are all loosely based on real events. The electrified pavement and the curious incident of the hawk and dog did happen, within a few hundred metres of one another. Every so often a child dies in an animal attack, though it tends to be dogs not birds of prey. The road rage happened too, though all the characters have been changed here and some events altered. Some may remember, more sombrely, the story of

Ryan Jones in 2007, an 11-year-old shot dead in a pub car park in Liverpool, an innocent in the way of a gang feud. Or Baby P, as he was known, a 17-month-old boy who died after suffering more than 50 injuries over eight months at the hands of his mother, her boyfriend and his brother.