The Norm Chronicles (8 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

All this is part of a general problem with risk perception known as availability bias, although, as we say, ‘bias’ is a mean word for what is often just a result of the framing. Availability bias refers to the fact that some things come to mind or attention more readily than others: the gun-on-the-wall effect. And sure enough, it’s easier to think about events than non-events. Whatever it might mean to try to think about an event that doesn’t happen, it is not easy or intuitive.

Researchers in the 1970s, among them the psychologists Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky and Paul Slovic, ran dozens of human experiments to discover what influenced people’s estimation of risk.

4

They noticed that after a natural disaster people took out more insurance, then with time took out less. This was not because the risk rises immediately after a disaster then falls, obviously, but because the risk is more salient immediately after a disaster.

Slovic also found that tornadoes were seen as more frequent killers than asthma, although the latter caused 20 times more deaths. As we will also see in the chapter on crime, vivid events are recalled not merely more vividly but in the belief there are more of them. Put crudely, we worry more that something might get us not because it’s more likely to get us but because it would make better telly.

This is a bias that can strike en masse, especially if we frame it right. The media play a part, and Kahneman uses the term ‘availability cascade’ to

describe the surge of interest, attention to new cases and panic that come with a scary but rare event. In contrast, problems that are common are not surprising and are less likely to qualify as big ‘news’. Another smoking death? And? So things that are genuinely likely to get you are not reported nearly so often as others that are rare. The unusual is, by the nature of news, disproportionately reported, so we think it more common.

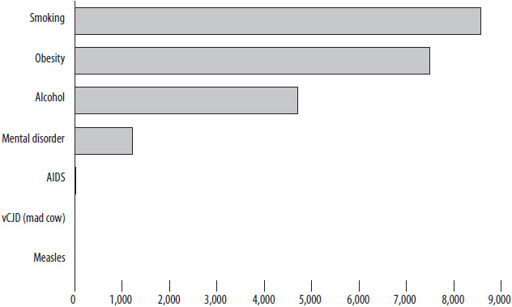

Figure 6:

The number of deaths from each cause in a year, for each story appearing on BBC news, i.e. deaths per story

Although this is a reporting bias, the media have no trouble justifying it on the grounds that people want to know about what’s unusual and new, not what’s old. There is no way they could report risk proportionately and still be in business. It would mean thousands of times more articles on smoking than on death from measles. But it is a bias, and although it is only speculation that this reporting bias affects people’s estimation of the size of different risks, it seems like reasonable speculation. The extent of the bias has even been quantified – see

Figure 6

above.

5

Mad cow disease, measles and AIDS received massive coverage relative to the number of people who died, whereas smoking, obesity and alcohol received little. The precise numbers of deaths attributable to all of these is debatable, and the fashion for certain stories has changed since the research was carried out more than a decade ago, but the thrust of the argument seems fair.

So there are all kinds of reasons why risk depends on what we pay attention to. This is partly because our attention is scatty, but also because it’s not clear which version of the numbers is the one to watch: the numbers about what happens or the numbers about what doesn’t.

5

ACCIDENTS

T

HEY WERE 11

, Norm and Kelvin, the time they went to swim in the reservoir. It was warm as they pedalled along the lanes, and when they arrived the water looked cool. They threw down their bikes by the reeds, trod off their trainers, stripped to their pants – Norm’s blue, Kelvin’s white – and stood on the grass bank not far past the two fishermen. The dare should have been a breeze, to be honest, but Norm hadn’t figured on the wind-up.

‘No, really, they do!’ said Kelvin. ‘They’re that long, with these evil teeth and they creep up underneath and go [snapping his jaws together] gnah!’

‘Yeah, but not your bollocks,’ said Norm.

Kelvin made rabbity, nibbling movements with his top teeth against his bottom lip, leaving brief pale slots in the pink skin.

‘No way!’ said Norm, looking away.

‘Big. And pointed.’

Kelvin paused. Norm felt the breeze.

‘Chew your knob off.’

‘Shut up.’

‘Here, pikey-pikey, Norm knob!’

‘

Shut up

!’

For a moment there was only the water beating at the reservoir wall and the wind in the reeds.

‘What’s up?’ said Kelvin. ‘Cold?’

‘Nah. You?’

‘Nah.’

Norm half-folded his arms, then let them drop.

‘So … scared, then? Or what?’

‘Me? Scared?’ ‘Go on then.’

The water chopped, and the waves slapped.

‘Dive, yeah?’

‘Yeah, ’course, dive.’

‘You do it then.’

Danger isn’t a choice at the age of 11; it’s a game with rules. Kelvin stood on the edge looking at Norm over cupped hands. Then his arms flew back, his body was a breath and a twitch, his white legs flexed and leapt.

Kelvin was in, smashed by cold, then above the water, hitching up his pants, head high, blowing at choppy peaks across the reservoir. Norm twitched too. But his body refused. His feet held to the ground.

Norm picked up his clothes and held them to his chest, eyes on the dark head in the waves, his thoughts on the precious last inch of cold flesh in his underpants and the imagined snap and rip of a pike.

On the outside, Kelvin looked hard and fearless. On the bank, Norm was transfixed by a toothy, jelly-eyed monster like something he’d seen in a fish shop, staring at him close-up. As Kelvin pulled through the murk towards a soaked wooden platform on the far side, Norm cupped a hand between his legs.

Kelvin’s swim to the platform would have been cold. Once there, climbing out seemed stupid as soon as he’d done it, except that Kelvin did it and Norm didn’t. Then what? Swim back. Colder still.

As Kelvin swam his last, slower strokes, Norm looked down, one hand clutching his clothes, the other still down his underpants. Out of the corner of his eye he noticed the fishermen again. A shout, ‘Oi!’, turned into a clatter of wellies. Running.

Norm looked up: flapping boots, chopping water, running and shouting. He turned back to see Kelvin climb out, wherever that was.

He looked left then right, up and out over the water for the pale body and the dark hair.

‘Kelvin?’

He twisted round. Looked back again for the place he’d missed. He saw water, green with flecks of grey and low, chopping waves, the platform, the bank, Kelvin’s clothes.

‘Jesus,’ he mumbled and stared again.

‘Kelvin!’

But there was no hair, no skin. Instead, his mind filled with the jelly eye and the sharp teeth, the eye, bite and blood. Fishermen plunged past into the water and the reeds hissed in the breeze.

He was white when they found him. But there was no blood. Still had bollocks too. The water did it, or maybe the cold. He wasn’t far out, or very deep. Three more strokes, they said. He should have shouted, but the fishermen said he just went under. It wasn’t Norm’s fault, adults said.

Later, Norm felt vaguely disappointed that the big thing hadn’t happened and his friend didn’t die. Not even brain damage, they said. Then Norm felt vaguely guilty for feeling vaguely disappointed. At school on Monday it was cool to be Kelvin. Norm would have liked to be cool too, but he was still thinking about teeth and jelly eyes.

THERE ARE TWO WAYS

to judge the risk of being bitten by a pike. One is ‘Don’t be daft, what pike?’ Even if there are pike, they probably have zero appetite for Norm’s willy. On the other hand, we could say the risk is stratospheric – because, come on, this is his willy he’s thinking of. After that, what more needs to be said? The risk is beyond imagining.

This difference in these two calculations of the same risk is that between probability and consequence. Probability describes the chance of being bitten; consequence is the answer to the ‘what if …?’ question. Is it likely he would have been bitten? Who knows? Probably not. But

what if

…? Same risk, different perspective, sea-change in emotion and anxiety. Norm’s struggle on the bank is between long odds and imagined agony. No prizes for guessing which grabs his attention. Just follow his left hand.

Fatal accidents are often like that: rare but terrible to think of. It is

rare for children of Norm’s age to drown: about 1 or 2 in every million children in the UK aged between 5 and 14 die through ‘accidental drowning and submersion’, each year, and about 3 or 4 in a million for those younger than 5. The figures are higher for males than for females at all ages.

1

There are no official figures for death by drowning by pike.

Even on the roads – where the threat of an accident is perhaps most apparent to parents (like us) who have clutched their children’s hands – it is increasingly rare for children to die. But all this is little consolation if you think of consequences not probabilities. One in a million, as Prudence’s mother said in

Chapter 2

, is useless to the one.

Take the true story of Mark McCullough, father of a seven-year-old girl who allowed her to walk the 20 metres from their home to the bus stop on the way to school each day, unaccompanied. Naturally, reported the

Daily Telegraph

in September 2010, he was threatened by a council with ‘child protection issues’.

2

The walk meant crossing a ‘busy road’ (said the council) or ‘quiet country lane’ (said Mr McCullough). The council was probably ‘only doing its job’. Mr McCullough was ‘very angry’. ‘It’s an absolute joke,’ he said: ‘I am not going to wrap my children up in cotton wool.’ A fact confirmed one chilly morning when his daughter was spotted ‘without a jumper’, said the shocked Head of Transport Services.

As with drowning, the figures for the kind of accident the council fears are low. In 2008 in England and Wales there were 1,471,100 girls aged between 5 and 9. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) says 137 of them died from all causes. Seven died in transport accidents. One was a pedestrian.

*

This is an average risk of less than 1 MicroMort per year. That is, 1/365th of the average daily risk of acute death for a UK adult. As we show below, more children die each year strangled by cords on window blinds.

Put aside arguments about parental responsibility and freedom. Concentrate on the risk – and answer an awkward question: which are most compelling, the basement-level mortality statistics, or the heightened fears of Lincolnshire County Council?

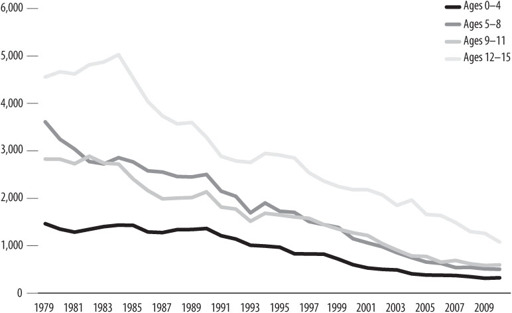

Figure 7:

Children killed and seriously injured on the roads, UK, 1979–2010

3

If you back the council, it may be because you feel the pull of what’s called the ‘asymmetry of regret’, better known as ‘How would you feel if …?’ How would you feel if you took your child to and from the bus stop every day and your worst regret was that you wasted a few minutes to prevent an accident that was probably never going to happen anyway? Not entirely happy maybe, but in the scheme of things the time and effort are no big loss. Next, how would you feel if you did not give up those few minutes, then one sunny morning over toast and marmalade you heard the squeal of brakes?

Choosing what to do in life by trying to minimise what you might most regret is known in decision theory,

4

naturally enough, as minimax regret. Most decisions are here and now. Imagined future regret is a tortured complication. It’s more than the difference between short-and long-term self-interest. It twists the knife with potential guilt and blame, imagines this as if experienced with hindsight, then makes that anticipated-retrospective feeling our main motive, if you follow. It is a roundabout way of deciding what to do which people calculate in a blink. But at its most tyrannical, mini-max regret makes us slaves of nightmares. A bad ending foreseen or imagined comes to justify the

most drastic avoidance. Does it also save lives? Thomas Hardy said that fear is the mother of foresight. In the TV series

The Simpsons

‘just think of the children’ is a joke that could be about mini-max regret. For some, it is a compulsion.