Read The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year Online

Authors: Linda Raedisch

Tags: #Non-Fiction

The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year (22 page)

176 There are Witches in the Air

could not walk through walls at Christmas or at any other

time of the year; that was for ghosts. Most often, witches entered the house through the door or window just like

everyone else. White or gray witches were able to walk in

the church door to attend Midnight Mass, but black witches had to stay outside or risk becoming distinctly unwell. The Somerset witch’s favorite route, however, was through the

chimney, and in this she was not alone.

In Norway, too, Christmas Eve was a great traveling

night for witches. Not just brooms but stools, staves and

fireplace tools were hidden away to prevent the witches

from stealing and riding them. This, of course, was no

obstacle to the witch who possessed an Icelandic Witch’s

Bridle, for she could transform anything, even a wash-

board, into a fast-moving vehicle just by laying the bri-

dle upon it. Where there’s a witch, there’s a way, and many of them probably kept their own stashes of extra broomsticks under the floorboards or in secret cupboards under

the stairs.38 The typical folkloric witch also had a hornful of flying ointment with which she could anoint household

objects to make them hover in the air like spaceships.

38. Such a stash was discovered in an old house in Wellington, England in 1887 when demolition work revealed a hidden room

inside the attic containing a comfy chair, a collection of six heather brooms and a rope into which crow, rook and white

goose feathers had been woven. This “witch’s ladder,” as it was identified by the workmen, was apparently used to work black magic, not to get from one place to another. In his book,

History

of Wellington

, A. L. Humphrey suggests it was used to cross from rooftop to rooftop, but surely that was what the brooms were for? Taking their cue from early Wiccan writers such as Gerald Gardner, modern Witches use the witches’ ladder, also known as a “wishing rope” or sewel, to work white magic. The last occupant of the house in Wellington was an old woman.

How she was supposed to have gotten in and out of the hidden room where she kept her broomsticks we are not told.

There are Witches in the Air 177

Knowing all this, Norwegian peasants spent the dark-

est hours of Christmas Eve trying to shoot the witches out of the sky like pigeons. But if you wanted to save your buck-shot, all you real y had to do was call out the names of suspected witches, causing them to fal in mid-flight. Where

were all of these witches supposed to be going? The bright meadows of Jonses, a mountain in eastern Norway, was

a popular destination at Easter and Midsummer, but on

Christmas Eve, the place to be was “Blue Knolls.” There,

all the witches who had signed their names in the big book belonging to “Old Erik,” as the Devil was fondly known,

gathered in the snow to hold their own feast apart from the Christian folk on the farms below.

In his childhood memoir,

When I Was a Boy in Norway

, Dr. J. O. Hall claims that the English Yule Log was original y a Norwegian import. If this is true, then the idea that the ashes of the Yule Log will keep witches away probably

also came from Norway. The Norwegian housewife who

was still worried about witches sliding down the chimney

on Christmas Eve could throw salt on the flames of the Yule Log, for there was nothing like a blue fire to deter a witch.

While the presence of a glittering Christmas tree was

not enough to keep a witch out, dried spruce boughs laid

on the fire might, for the dry needles created an explosion of sparks that frightened the witches away. Today, firecrackers are used to the same end, but are they as effective? It may not have been just the flash and the noise that was supposed to put the witches off but the concentrated essence of evergreen. Throughout Europe, on al the most dangerous

nights of the year, the farmer made the rounds of his out-

buildings with a brush and a bucket of pine tar, for the vig-178 There are Witches in the Air

orously turpentiney scent of pine tar which many of us find pleasantly heady is apparently repel ant to witches.

Scandinavians have been distilling tar from the split

roots of

Pinus sylvestris

since time out of mind. In the old days, the distillation process took place in earth-covered kilns in the forest, so perhaps Snorri’s subterranean Black Elves were actually ancient kiln-watchers. The Norsemen

used pine tar to waterproof their boats when they went

a-viking, using the leftovers in the bucket to paint black crosses, or in those days Thor’s hammers, above the farmhouse door and above each stall in the cow byre. Just about anywhere in Europe where pine trees grew, pine tar crosses were painted at strategic points around the homestead.

Such crosses could be stroked onto the beams at any time,

but they should be given a fresh coat at Walpurgis Night,

Midsummer and, of course, Christmas Eve.

Rise of the House of Knusper

On December 23, 1893, Engelbert Humperdinck’s

Han-

sel and Gretel

, a “fairy opera,” premiered at the Hofthe-ater in Weimar with Richard Strauss conducting. This was

the beginning of a Christmas tradition that has lasted to

this day, but it was also the most recent development in

an older, edible Germanic tradition. Eighty-one years ear-

lier, the story of Hansel and Gretel first appeared in print in

Household Stories

by the Brothers Grimm. “Hansel and Gretel,” the fairytale, is an example of Tale Type 327 in which a child or children defeat an ogre or witch. Tale Type 327 is found all over Europe, so who knows how old it might be?

One theory is that it grew out of the Great Famine of 1315-There are Witches in the Air 179

1320, but this theory overlooks the fact that poverty and

hunger were ongoing issues for peasant families until very recent times.

Even before the opera’s premiere, “Hansel and Gre-

tel” was considered a Christmas story, perhaps because it

featured an edible house.39 The Brothers Grimm say only

that the witch’s house “was built of bread and roofed with cakes,” but few Germans would consider building a witch’s

house out of anything but

Lebkuchen

. What is the difference between Lebkuchen and gingergread? Lebkuchen,

which is eaten in many shapes throughout the Christ-

mas season, contains no ginger. The

Lebkuchenhäuschen

, which also goes by the name

Hexenhäuschen

(“witch’s cottage”) and

Knusperhäuschen

(“crunchy cottage”) and even

“

Knisper-Knasper-Knusperhaus

,” as it is referred to in Act I of the opera, is a staple of the German, Swiss and Austrian Christmas. In the folksong, “Hänsel und Gretel,” of

uncertain date, the witch’s house is made of

Pfefferkuchen

, another ubiquitous German Christmas cookie that comes

coated in hard white icing. So perhaps the snow-bedecked

witch’s house represents a Christmas tradition independent of either the Grimms or the Humperdincks.

39. “The Three Little Men in the Wood,” another of the Grimms’

fairytales, was apparently never even in the running to become a seasonal opera, even though it opens in the snowbound forest.

“Three Little Men” features the almost universal “berries in winter” folktale motif as well as incorporating elements of Cinderel a, Snow White and Frau Holle, with the heroine taking on shades of White Lady toward the end of the tale. But, unlike

“Hansel and Gretel,” “The Three Little Men” has neither a witch nor a Lebkuchen house, so I suppose there was real y no contest.

180 There are Witches in the Air

It was the composer’s sister, Adelheid Wette, who, work-

ing from the Grimms’ story, wrote a poem about Hansel and

Gretel for her children to perform at home on Christmas. No doubt this was one of those dreaded recitations which many German children are still forced to deliver in front of the decorated tree on Christmas Eve. In Adelheid’s version, the mother sends the children out in a fit of temper; it’s not pre-meditated abandonment. She is not nearly as heartless as the stepmother in the Grimms’ version of the story, who sniffs,

“’Better get the coffins ready!’” when the children’s father balks at her plan. Just to confuse the issue, many productions cast the same singer as both the mother and the witch. At

other times, the witch may be sung by a male tenor, while the role of Hansel is often sung by a woman.

The opera does not actually take place at Christmas-

time; the only fir trees are the ones clustered at the foot of the Ilsenstein where the witch’s cottage appears. In the first act, the father, a broom-maker, mentions that the vil agers are preparing for a feast. This is probably St. John’s Day, or Midsummer, since his children are at the same time picking wild strawberries40 at the foot of the aforementioned Ilsenstein, a knobbly stone protuberance poking its head out of the dark forest of the Harz in order to get a good look at the nearby Brocken, a mountain known by all Germans to

be heavily frequented by witches. Coming home drunk, the

father boasts to his wife that he has sold his entire stock of besoms. One cannot help but wonder if he might have sold

40. In “The Three Little Men,” the wicked stepmother sends the un-named heroine out in a paper frock to gather strawberries in the snow.

There are Witches in the Air 181

one of them to the Nibbling Witch who will soon try to

cook his children, for the Nibbling Witch likes to circle her house on a broomstick.

If you don’t already know how it al ends, or even if you

do, you can host a showing of

Hansel and Gretel

at home.

There are a number of productions from which to choose.

You might try the 1998 DVD

Haensel und Gretel

directed by Frank Corsaro, in which the sets and costumes are designed by Maurice Sendak. (I, for one, would not dare to take a bite out of Sendak’s witch’s house no matter how hungry I was;

it has eyes!) Unfortunately, there is no DVD of Tim Bur-

ton’s live action, strongly Japanese-flavored

Hansel and Gretel

which appeared on the Disney Channel on Halloween 1982.

Like most of the world, I’ve never actual y seen Burton’s version, but it can’t be any creepier than the 1954 stop-action

Hansel and Gretel: An Opera Fantasy

directed by Michael Myberg. For movie snacks, I suggest almonds and raisins, the foods the witch fed to Hansel to fatten him up.

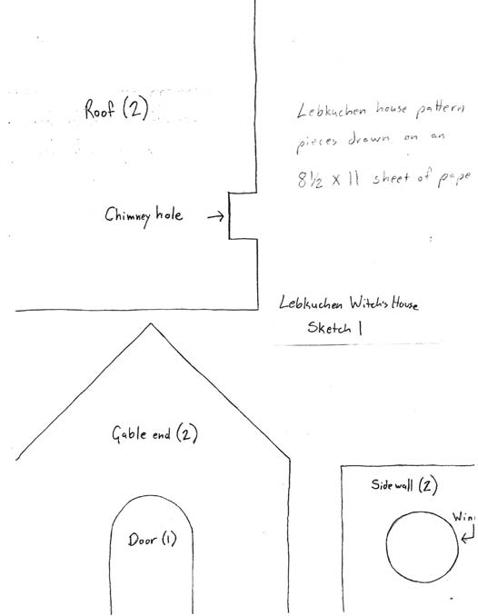

Craft/Recipe: Lebkuchen Witch’s House

Before you decide that this project is too much for you,

keep in mind that Lebkuchen is rolled out much thicker

than gingerbread cookie dough. These thicker walls make

the house quite easy to assemble.

The following instructions will make one Witch’s House

about 4 inches high, 4½ inches wide and 6 inches long in

a garden that’s about 5½ inches wide and 8 inches long,

with a little dough left over for details like shutters, paving stones, animal familiars or whatever else you can dream up.

Or, you can bake the extra dough into cookies for immedi-

ate eating. Because I like a hollow chimney through which

182 There are Witches in the Air

smoke can escape, I build mine out of dark chocolate seg-

ments. My German grandmother, however, made hers out

of a solid, heavy piece of dough. When the chimney fell in, it was time to eat the house.

Overhanging eaves are another hallmark of the tradi-

tional Witch’s House. This leaves lots of room for icicles, which can be made with a quick sweep of a fork or knife.

Since this is a humble, homemade sort of cottage, you will not be called upon to wrestle with a pastry bag.

In Germany, the door of the Witch’s House is usually

left ajar to entice Hansel and Gretel inside. An open door also allows you to put a tea light inside to illuminate the windows which can be glazed with dried lemon or orange

slices, Fruit Roll-Ups or—my personal favorite—small

sheets of roasted seaweed. If you make a hollow chim-

ney, the smoke from the blown-out tea light will drift up

through it.

The green seaweed windows combined with a lot of

black licorice accents will convey a sense of poorly sup-

pressed witchiness. I have placed two Trader Joe’s Black

Licorice Scottie Dogs in my garden along with a chocolate

Christmas tree for their convenience. (You could also put

a few black licorice cats on the roof.) For a final touch, I snipped the end of a black licorice stick into a brush and left it sticking out of the chimney. We can only hope that the chimney sweep to whom it belonged did not end up in

the witch’s oven!

Step 1: The Template

All you need to make a template is a sheet of 8½" x 11" paper, a pencil and a pair of scissors. Draw the pieces as shown or