Read The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year Online

Authors: Linda Raedisch

Tags: #Non-Fiction

The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year (21 page)

166 Winter's Bride

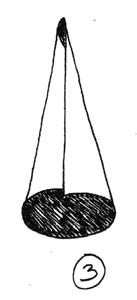

going to make more than one mask. Turn the cut-out quar-

ter into a cone and glue the seam. (Figure 3)

Lucka Mask Figure 2

Lucka Mask Figure 3

Winter's Bride 167

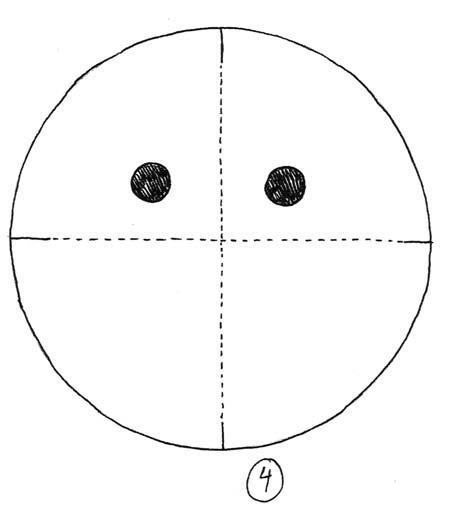

Using a large coin as a template, trace two eyeholes on

the small circle as shown in Figure 4. cut out eyeholes with your knife.

Lucka Mask Figure 4

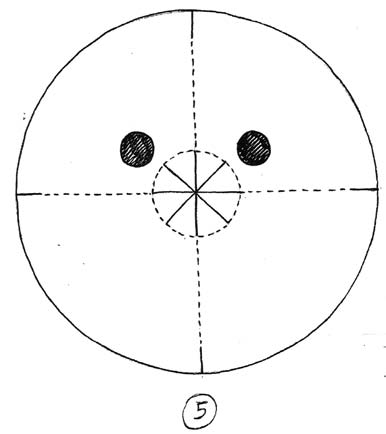

Use the base of your cone to trace a circle in the cen-

ter of the mask. With your knife, divide the circle into “pie slices” as shown in Figure 5, but

do not

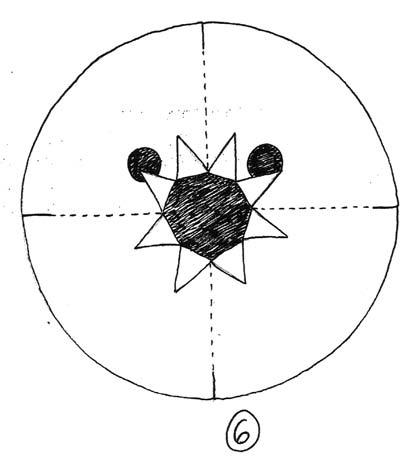

cut out the circle itself. Fold the “pie slices” up and back as shown in Figure 6.

168 Winter's Bride

Lucka Mask Figure 5

Lucka Mask Figure 6

Winter's Bride 169

Slide the cone out through the hole in the center of the

mask. Glue the “pie slices” to the base of the cone to hold it in place.

It’s time to use those four cuts you made at the edge of

the mask. Starting at the forehead, slide the edges of the cut one over the other and glue in place. Do the chin next, then the cheeks. Punch a hole at the side of each cheek and tie a length of yarn or ribbon in each hole.

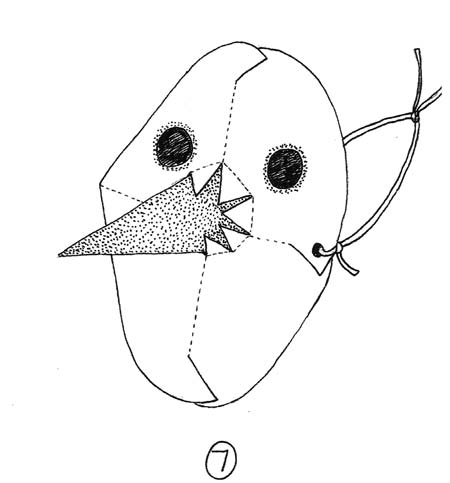

Figure 7 shows the finished mask with silver glitter

applied on the nose and around the eyeholes. There is no

mouth because the Lucka traditionally does not speak.

Lucka Mask Figure 7

170 Winter's Bride

Rising from the Ashes

Meanwhile, in Rosenberg, the

Lucu

, three youths dressed in white, entered the house with broom, bucket and mop.

Without a word, they proceeded to whisk and wash away

until the housewife presented each of them with a small

gift. Like the equally mysterious Slavic “Sweeper” who

entered homes silently during Advent to brush the stove

three times with her bundle of birch twigs, the Lucu’s services were more of a blessing than a thorough cleaning.

Further to the east, there was a Slovakian Lucka who

glided silently with face veiled through all the nights

between her feast day and Christmas Eve. The Slovakian

Lucka reminds us of both the Barborky and the scarecrow

brides who, not unlike those virginal Christian martyrs,

were stabbed, burned, and/or cast into rivers.

Back in Sicily, Lucia Night is celebrated with bonfires,

though the saint’s image is never thrown into the flames.

Lucia has proven herself to be one of the most resil-

ient saints, having survived the Reformation in both the

Lutheran and Anglican churches. There’s really no need

to feel sorry for her, especially when you take into account her striking resemblance to Aurora, Roman goddess of the

dawn. If not Aurora, then the first Lucia was probably some native Sicilian equivalent thereof. In Sicily, she also served as a gift-giver, coming down the chimney in her witch’s

weeds, not her saintly garments. This Lucia threw ashes in the eyes of any child she caught spying on her. The saint, we are told, gouged her own eyes out to make herself less

attractive to potential suitors, but the throwing of the ashes

Winter's Bride 171

strikes one as a reminder never to look directly at the sun or at secretive gift-givers.

Regardless of whether or not she ever actually existed,

the Sicilian Santa Lucia aspired to become the bride of

Christ. Still a virgin, she now banishes the winter darkness with a brave display of candlelight. The Lucka and Lus-sibrud on the other hand, consumed the night, taking it

with her when she left the village so that the hours of day-light might increase. In Bohemia, she was said to “drink the night.” This older Lucy was the bride of Death, the midwinter darkness her dowry. As such, she provided an invaluable service to the far-flung communities of farmers and herds-men to which she had been born. No Christian saint could

quite replace her.

With the Old Solstice behind us and Christmas on its

way, have we now seen the last of the glowing, bride-like

Midwinter Witch? No, we have not, for, as the cast-down

White Witch in

Prince Caspian

says herself, “’[W]ho ever heard of a witch that really died? You can always get them back.’”

There are Witches in the Air

It was once the custom of Austrian farm wives to go out

to the orchard at midnight on St. Andrew’s Eve (Novem-

ber 29) to break branches from the apricot trees. They

forced the branches into flower in vases at home then car-

ried them to church on Christmas Eve. The white blos-

soms must have looked quite striking against the wives’

dark wool Sunday dresses, but it was not these ladies’ intention to create a pretty tableau; the flowering apricot branch allowed the bearer to pick out any witches in the congrega-tion. What set the Austrian witch apart? Well, if you had an apricot branch, you would notice she carried a wooden pail on her head. I don’t know about witches, but the practice

must have been an effective means of identifying the par-

ish busybodies.

St. Andrew’s Day is an important fingerpost along the

road to Christmas. There are two systems in place for calculating the beginning of Advent, the ecclesiastical Christmas season. One is to count back from the fourth Sunday before Christmas Day. The other is to locate the Sunday closest to

173

174 There are Witches in the Air

St. Andrew’s Day. In most Catholic and formerly Catholic

regions, St. Andrew’s Day is the cue to start planning a happy holiday, but it is the darker occasion of St. Andrew’s Eve, and the ensuing Christmas season, which concerns us here.

Vampires

While the Austrian witches were scouring their milk pails

and Polish girls were busy pouring lead into cold water to find out when and to whom they would be married, the

Romanians had bigger problems. In Romania, St. Andrew’s

Eve was not a night to go out, let alone to go wandering

in the orchard. It was not enough to lock the doors; before dark, all apertures had to be thoroughly rubbed with a

peeled garlic clove, for on this night the vampires clawed their way out of their graves and walked again. Carrying

their coffins portage-style, they paraded into the village to circle their former homes before taking themselves to the

crossroads to engage in a pitched battle, no doubt with the vampires of the neighboring village.

A cross placed, chalked or painted over a door or cat-

tle stall imparts protection to the occupant, but a cross

roads

has always been the haunt of witches and other malevolent spirits, perhaps because suicides were buried and outlaws left to rot there. The Apostle Andrew whose night this is was martyred on an X-shaped cross. His feast day marks

a crossroads within the year, for it was acknowledged in

much of Europe as the true beginning of winter.

Joining these more usual vampires at the crossroads

were the village’s congenital vampires. This could be a seventh son or an individual whose mother had neglected to

pull out the one or two teeth with which he had been born.

There are Witches in the Air 175

The soul of this kind of vampire left his sleeping body as a blue flame flying out through the mouth. Between home

and the crossroads, it assumed the shape of that vampire’s personal animal, so even the nosy neighbor who was brave

enough to peer out the window would have no idea to

whom the fiery blue dog flying by might belong. Cockcrow

sent both species of vampire scuttling back to their graves and their beds on the morning of St. Andrew’s Day.

In his mammoth work,

The Golden Bough

, Sir James

George Frazer describes another sort of “vampyre” afoot in Romania. This one might be kept at bay with the “need fire”

which was kindled afresh after all fires in the community

had been extinguished. The need fire was used to purify

and protect the cattle from diseases which these vampires

were thought to cause. Unlike Bram Stoker’s or Stephenie

Meyer’s undead, these vampyres were incorporeal.37 Frazer

contrasts them with “living witches,” classing them instead with “other evil spirits.” Though filtered first through German and then through French, the term “vampire” arrived

in English almost untouched from Serbian. The word is

so old that its etymology is uncertain, though it may have come from the Turkish

ubyr

which means simply “witch.”

Down with a Bound

Long before the introduction of “floo-powder,” there was

already a lot of coming and going through the fireplace flue as the witches floated nimbly both up and down the chim-bley. In Somerset, the general consensus was that witches

37. For a thorough treatment of some distressingly corporeal vampires, see Paul Barber’s

Vampires, Burial and Death

, if you have the stomach for it.