The Oxford History of the Biblical World (67 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

Another way of assessing the decree of Cyrus is to look at the visual arts. Cyrus’s appeals to Marduk in the cylinder and to Yahweh in the biblical decree demonstrate the Persian tendency to co-opt local religious and political traditions in the interest of imperial control. The artistic record corroborates this. Margaret C. Root has outlined the Persians’ carefully calculated imperial program, designed to convey a vision of hierarchical order and imperial harmony over which presided the benevolent but omnipotent great king. To communicate this ideology the Persians brilliantly synthesized history and art according to the traditions of their subject peoples.

One outstanding example of this is the over-life-size granite statue of Darius I discovered in 1972 by French excavators at Susa in the Persian heartland. Made in

and intended for Egypt, the statue remarkably mixes linguistic and artistic vocabularies. Darius stands in a conventional Egyptian pose but wears a Persian robe; the cuneiform text inscribed on the robe glorifies Darius as a conqueror. By contrast, the accompanying hieroglyphic inscription on the base tactfully dispenses with the conqueror references, proclaiming Darius as pharaoh, “King of Upper and Lower Egypt,” with additional titulary. Tellingly, beneath Darius’s feet appear not the traditional bound enemies of Egypt but personifications of Darius’s subject peoples raising their hands in an Egyptian gesture of reverential support previously reserved for divine beings. Just as Cyrus speaks only of Marduk to the Babylonians and of Yahweh to the Judeans, for the Egyptians Darius becomes the pharaoh. Darius is also, however, a Persian pharaoh, less intent on calling attention to his dominating power over Egypt than in publishing the idea that all his various peoples are engaged in the harmonious support of his sovereignty.

The decree, or something like it, might have existed, along with the copy later found by King Darius’s archivists in the Persian summer capital Ecbatana (Ezra 6.1–5 [Aramaic]). At some point, whether 538 (the date could be symbolic) or somewhat later, an indeterminate number of exiles returned to Jerusalem. Their leader was the Persian province of Yehud’s first governor and a “prince of Judah,” Sheshbazzar (a Babylonian name), who had been entrusted with the financial contributions raised by the Babylonian Jews and with the 5,400 gold and silver Temple vessels returned by Cyrus (Ezra 1.6–11). The first group of returnees is said to have laid the foundations of the new Temple (Ezra 5.14–17), although Ezra 4.5 reports that attempts to build the Temple were frustrated until the second year of Darius (520) and the governorship of Zerubbabel. Likewise, the second quotation of Cyrus’s decree (Ezra 6) is silent on the subject of any exilic return to Judah in Sheshbazzar’s time, prompting the suggestion that no notable return of any sort occurred before 520, when Zerubbabel and Joshua began their building program. Josephus reports that Jews in Babylon were “unwilling to leave their possessions”

(Antiquities

11.1.3). Any returnees accompanying Sheshbazzar constituted only a portion of the Babylonian Jewish community, whose religious practices and beliefs were possibly heterogeneous.

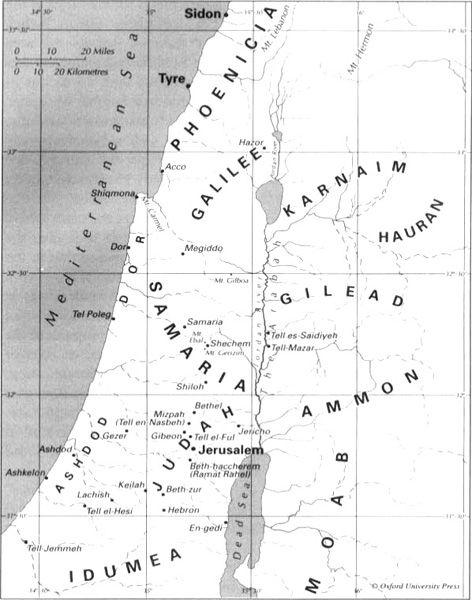

Yehud (Judah) was but one subprovince in the Persian fifth satrapy (Abar Nahara), which comprised Babylon (until 482), Syria-Palestine (including the coastal Phoenician city-states), and Cyprus. Unlike the Assyrians, the Babylonians had not brought deportees from elsewhere into Palestine. But Palestine was nevertheless the home of peoples who had been displaced and whose national identity had been threatened during the unrest of the sixth century: Philistines, Judahites, Samarians (both ethnic Israelites and settlers brought in by Assyria), Moabites, Ammonites, Edomites, Arabs, and, growing ever more influential, the Phoenicians, who dominated the entire Levantine coastal plain.

Over the two centuries of Persian rule the already mixed Phoenician culture absorbed increasingly greater doses of Cypriot and Aegean (Greek) elements as well. Impoverished inland areas such as the mountainous region of Judah, parts of Samaria, and perhaps Transjordan, whose economic life was based on grazing and agriculture, avoided heavy Phoenicianizing and consequent hellenization far longer than areas on the coastal plain or along trade routes, where industry and commerce flourished in the international common market of the Persian period. At the beginning and for much of the Persian period, Judah was poorer, less populous, and more isolated than the surrounding territories. Besides Jerusalem, other Judean sites, especially fortress cities, bear the marks of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadrezzar’s campaigns of destruction and conquest. Many urban sites, such as Hazor, Megiddo, Tell Jemmeh, Lachish, and Ashdod, although not abandoned now supported smaller unwalled settlements, often dominated by a large administrative building variously identified as a “fortress,” “residence,” or “open-court house.” Throughout the Persian period Jerusalem occupied only the eastern hill (the Ophel, originally captured by David) and the Temple Mount.

Palestine during the Persian Period

Most of the inhabitants mentioned in Ezra-Nehemiah are clustered in northern

Judah and Benjamin, areas which archaeological evidence shows suffered least at the hands of the Babylonian invaders (at sites such as Tell en-Nasbeh, Gibeon, Bethel, and Tell el-Ful) and where some degree of prosperity endured. Perhaps this area surrendered early to Babylon. Likewise, farther north in Samaria archaeological surveys indicate a continuity of settlement into the Persian period with no decline in population. In particular, small groups of farmhouses found in a number of regions in the Samarian countryside, even on marginal and rocky lands, attest to a flourishing, even growing, population in the province. Beyond Samaria, Galilee became heavily Phoenician, densely settled, and prosperous during the Persian period. And crowded along the coastal plain were numerous cities of a predominantly Phoenician nature, with the associated inland plains, especially the Shephelah, densely settled.

The nature of the Persian administration of Palestine, as well as the place within that system of Samaria and Judah, are still obscure. Because Persia took over the Babylonian empire at one stroke by conquering Babylon, it is supposed that in the early years of Persian control the Babylonian provincial and subprovincial framework remained in place. The Persian administrative center nearest to Jerusalem was at Mizpah (Tell en-Nasbeh; Neh. 3.7), formerly the seat of the Babylonian authorities (2 Kings 25). Actual Persian presence in Syria-Palestine is difficult to pinpoint in the archaeological record. The Persian authorities lived in widely scattered enclaves or military strong points linked by the remarkable Persian system of communication. The best known such enclave is the “Persian residency” at Lachish. Other such sites include Tel Poleg and Shiqmona on the coastal plain, Tell el-Hesi, whose fortification system is one of the largest known mud-brick structures of the Persian period in Palestine, Ramat Rahel (Beth-haccherem) south of Jerusalem, En-gedi near the Dead Sea, and (in the Jordan Valley) Tell es-Saidiyeh and Tell Mazar.

The political designation applied by Persia to Judah and translated as “province” or “subprovince,” as well as the title

governor,

applied, for example, to Zerubbabel and Nehemiah, have a range of meanings. Neither term proves the autonomous status of Judah as a territory of the Persian empire or the exact hierarchical level of the Judean governor. Nevertheless, the terms are official ones in Achaemenid imperial administrative contexts. Sheshbazzar is the first in a series of governors of Yehud known variously from the Bible and from Judean seals and sealings. The cumulative evidence suggests that Yehud was an autonomous administrative unit and not part of the province of Samaria. The Neo-Babylonians did not collapse previously distinctive political territories (such as Judah and Israel [Samaria]) into new provinces, nor did they subsume one territory under the power of the authorities governing another, so it is unlikely that the Persians inherited such an unusual type of province.

The Shephelah west of the Judean hill country may have been under the control of the coastal city of Dor. Samerina (Samaria) was administered from its capital in Samaria by a series of governors belonging to the Sanballat family. Archaeological remains at sites in the Jezreel plain and southern Galilee show an orientation toward coastal Phoenician culture, but their administrative center is uncertain; perhaps Megiddo remained as the provincial capital, as it had been under the Assyrians and Babylonians. Northern Galilee may have been administered separately, from Hazor.

The capital of Idumea, south of Judah, is unknown. Idumea was settled primarily by Edomites but also perhaps by some Judeans (Neh. 11), the Edomites having been

forced out of their ancestral territory farther east by advancing Arab tribes. Beyond Idumea, Arabs, called “Kedarites” according to inscriptions from Tell el-Maskhuta in Egypt and from ancient Dedan (modern al-

c

Ula) in the north Arabian Hijaz, controlled northwest Arabia, southern Transjordan (former Edom), the Negeb and Sinai, and the coast around Gaza. The same inscriptions mention Geshem (known also from Neh. 2.19; 6.6) and later his son as leading the Arab federation. Herodotus reports that these Arabs were allies, not tributaries, of the Persian king. Across the Jordan, from north to south lay the provinces of Hauran, Karnaim (Bashan), Gilead, Ammon, and perhaps Moab. Excavations in Jordan suggest that in the sixth and fifth centuries

BCE

the land continued to be occupied and in some cases to flourish. On the coast clustered the Phoenician city-states, and the quasi-autonomous city-states or provinces of Acco, Dor, and Ashdod.

The Bible’s interest is restricted essentially to Jerusalem and the Judean hill country immediately around it, about 2,000 square kilometers (770 square miles). Compared to its preexilic extent, postexilic Yehud was sadly diminished. Reconstructions of the boundaries of the Persian province of Yehud have been based on a correlation between lists in Ezra-Nehemiah (Ezra 2.21–35; Neh. 3.2–22; 7.25–38; 12.28–29), the distribution of Judean seals and coins, and the results of archaeological surveys. All of these sources are problematic. Some towns in the biblical lists, particularly those in the Shephelah (the fertile low hills west of the Judean hill country), may not have belonged to Yehud but were instead places to which the returnees had ancestral connections. Some of the seals and coins used to determine boundaries come from the Hellenistic era, and some of the sites that had been interpreted as boundary fortifications may have been built to secure trade and communication routes rather than borders. Yehud’s northern boundary matches the preexilic tribal boundary line north of Mizpah and Bethel. The east was bounded by the Jordan River, thus including Jericho and En-gedi; and the southern edge followed a line from En-gedi to the Shephelah, running north of David’s first capital, Hebron (now in Edomite territory). According to Nehemiah 3, the province of Yehud was divided into five districts: Mizpah, Jerusalem, Beth-haccherem, Beth-zur, and Keilah (and some scholars add Jericho to the list). Precise district borders are disputed.

Not surprisingly, there are fewer sites in Judah in the Persian I period (539/8-ca. 450) than in Persian II (ca. 450–332). By the later period, the prosperity of the thriving eastern Mediterranean economy had begun to trickle down to Judah. The Egyptian revolt of 460 transformed Judah into a more strategically significant Persian possession, and the missions of Ezra and Nehemiah (second half of the fifth century), which were probably related to Persia’s Egyptian problems, marked the province’s rise in the Persians’ scale of importance. Exceedingly low population figures for Judah have been arrived at by recent demographic studies, based on the number of excavated and surveyed sites occupied in the Persian period. New modes of analysis have produced a tentative estimate of 32,250 for the population of Judah in the late preexilic years. In the Persian I period the population had dramatically fallen to 10,850, one-third Judah’s former size. By Persian II the number increases to 17,000.

These figures help put the biblical picture in perspective. For instance, Jerusalem’s population in Persian I has been calculated at a minuscule 475 to 500, which more than trebles to a still meager 1,750 in Persian II. There was no sizable population in

Jerusalem or Judah until the second century

BCE

. Numbers like these recall the biblical descriptions of exilic and postexilic Judah as devastated (Jer. 52.15–16; Zech. 7.7,14). They also explain the concerns expressed by Zechariah (8.4–8), Nehemiah (11.1–2), and Second Zechariah (Zech. 9–14, composed well into the Persian period) with repopulating Jerusalem and the land by means of exilic return and by divinely ordained human fruitfulness (Zech. 10.7–10).

A casual reading of the Bible, particularly Ezra-Nehemiah, could leave the impression that the land to which the exiles returned was utterly abandoned and depopulated. On the contrary, archaeology, common sense, and even the Bible indicate that part of the Judean population, although markedly diminished, had continued to live in Judah after the Babylonian deportations and flights of refugees to Egypt. There are a few scattered biblical allusions to Judeans who were never exiled. Jeremiah 39.10 mentions that after the destruction of Jerusalem the Babylonians gave vineyards and fields to poor Judahites. Perhaps the Jewish families assigned in Nehemiah 11 to cities south of Beth-zur (and thus technically outside the borders of Judah) had remained there during the exile.