The Rape of Europa (81 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

A few months later the MFAA officers were informed that the Army had been authorized “to return to refugee nationals or non-nationals of the Soviet

Union or Soviet satellites objects independently claimed by them” and were told to return the Dürers to Lubomirski “without publicity.” This was fine with the Prince, for not only did he not have a valid claim, the Dürers having indeed been given to the museum in the 1840s, he also had not told most of his relations about what he was doing. The drawings were sold in New York and the Prince, to the chagrin of the rest of the family, lived happily ever after, in some style. But the Lvov Museum, now in the independent nation of Ukraine, did not forget. Before his tragic death in 1992 at the hands of thieves, its director, Dmitri Shelest, inspired by the example of the Netherlands government in its quest for the Koenigs collection, had been considering making an international claim for the drawings.

40

The United States was not the only custodian nation to have problems with claims from the nations now under Soviet control. It would take the Canadian government nearly fifteen years to extricate itself from the complications surrounding the return of the Cracow Castle tapestries to which it had given refuge in 1940.

The problem of the Hungarian Crown of St. Stephen, another cause célebre, took even longer to resolve. It had been brought to Seventh Army Headquarters in May 1945 by a Hungarian colonel named Pajtas and an escort of twelve men, all sworn to guard it with their lives, which they had indeed been doing since 1943, moving it from place to place to keep it from the Red Army. The crown was packed in a locked chest with three locks, for which Pajtas claimed not to have the keys. Seventh Army promised not to force the box open and stored it under heavy guard, but word of the discovery leaked out and the press clamored to view it. A few weeks later the keys were “found,” but when the box was opened it was empty.

Colonel Pajtas now sheepishly admitted that he had known this all along and had in fact himself hidden the crown and other elements of the Hungarian regalia in a secret spot. The Americans pointed out that inability to produce the crown could lead to accusations of theft, which would not be good publicity for them, and persuaded Pajtas to retrieve it. This was done without official authorization in the dead of night. The regalia were found in a mud-covered oil drum. Pajtas and the MFAA men washed the jewels off in a bathroom and put them back in their original box, where with much hoopla they were displayed for the press, after which, sealed with wax imprinted with the dog tags of the Seventh Army Property Officer, they were taken off to the Reichsbank in Frankfurt to join all the other crowns.

41

Despite Hungary’s status as an Axis-allied country which was supposed

to wait until last for restitution, in April 1947 the United States, in a futile effort to stabilize the country’s political situation, returned a number of things, including a large quantity of silver and gold bullion removed by the Nazis and the contents of the Budapest Museum. But the ill-fated Prime Minister Ferenc Nagy, fearing that the arrival of the crown would exacerbate unrest, made it known that he preferred that the sacred object not be returned. After a time the Army quietly sent it to Fort Knox. The Hungarians made sporadic claims and threats that were resisted until 1977, when President Jimmy Carter decided the crown could go home. The process was still fraught with controversy. Hungarian refugees in the United States protested and marched on the White House. The Hungarian government had a different problem: they had heard that the crown was to be returned by

Mrs.

Carter and cabled that “with all respect for the emancipation of women, we should very much prefer a high U.S. official and possibly a delegation from the U.S. Congress.” The Congress, always up for a junket, happily obliged, and the crown was delivered by Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and a group from the Hill on January 6, 1978.

42

In August 1948 General Clay tried to set a final deadline for restitution to the occupied lands. The foreign representatives at the Collecting Points were told that all their claims must be submitted by September 15, and that action on them would end on December 31. Working day and night, the MFAA representatives completed hundreds of cases, but to the dismay of the claimant nations many remained unresolved at the time of the deadline. They need not have worried: the men at the Collecting Points would continue for three more years to arrange the return of identifiable objects to claimant nations. This left the so-called internal loot: objects confiscated from German nationals, legitimate German-owned cultural property, and, most difficult of all, the unclaimed property of the dead, or “heirless property.”

Clay had ordered as early as April 1947 that German-“owned” property be turned over to the German administrations of the Länder, which were to pass their own regulations for distributing the property. The MFAA officers did not find this at all acceptable, fearing that the Germans, once in control, would not check the origins of such works and return material that proved to be loot. And indeed Länder officials had immediately complained that the December 1948 cutoff for claims allowed too much time. After proposing various ideas advantageous to Germany, such as lower liability for lost works, they finally refused to pass a general restitution law as it could not be applied in the Russian Zone, where no one was bothering with restitution at all. The ball was thus back in Clay’s court, and the

Military Government was forced to supervise regulation of the internal as well as the foreign restitution process. This was done in cooperation with the German courts and regulated by the provisions of Military Government Law 59, passed in November 1947. After a time the French and British did the same in their zones, and through this process hundreds of thousands of objects were released to German claimants.

43

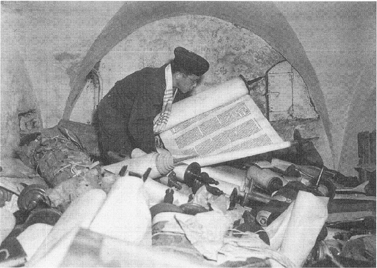

Chaplain Samuel Blinder sorts Torah scrolls at the Offenbach Collecting Point.

The problem of “heirless” Jewish property still remained to be solved. Traditionally, unclaimed cultural property reverted to the state and was distributed among museums and libraries. This was clearly out of the question for nations where whole populations had been killed or forced to flee, never to return. The idea of a supranational commission of cultural adjudication which would try to salvage and decide on the disposal of works of art, so long discussed in the free nations during the war, at last came into being for the unclaimed Jewish property. The process was not smooth. The French and British were opposed to the whole idea; the Russians, as usual, did not participate at all. But in the United States Zone a regulation was added to Military Government Law 59 allowing a charitable or nonprofit group to act as a “successor organization” which, instead of an individual state, could claim heirless Jewish property. The Jewish

Restitution Successor Organization (JRSO), founded in New York in 1947 to represent Jewish groups from all over Europe and Palestine, took on this task. A second organization, Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, worked with the JRSO on the difficult task of distributing religious and cultural objects to groups worldwide. Final arrangements on the details of transfer and shipping were not completed until February 1949.

As usual, Clay pushed the issue: the JCR was given an impossible three months to organize removal of the heirless objects from the U.S. Zone. There were more than a quarter of a million books—as well as thousands of Torah scrolls, ceremonial textiles, and ritual vessels—still at the Offenbach Collecting Point alone, where the objects Lincoln Kirstein had found at Hungen and much more had been taken. This had been distilled down from the original million or so by the extraordinary efforts of Captain Seymour Pomrenze, a former employee of the National Archives in Washington, who had sent back tons of books to the Western occupied nations.

Mercifully for the three scholars attempting to divide the books, the deadline was extended for a further three months. The vast majority of objects went to Israel and the United States, but the distribution was fraught with conflicts. The few Jews remaining in Germany did not wish the relics of their devastated communities to go abroad, even though many of their people were in the receiving countries. Nor did German gentile communities always give up valuable Jewish manuscripts and archives with grace. The disputes would go on for many years and become entwined with the settlements eventually arranged between Germany and the state of Israel.

44

Despite all Clay’s efforts, the Collecting Points were still not empty when he left Germany in May 1949. The remaining stores of art and archives would require the attention of specialists for many more years. For the final American push Ardelia Hall at the State Department recruited old hands Thomas Howe and Lane Faison, who closed down the Collecting Points in September 1951. The remaining “items,” still quite a number, were handed over to another German “Treuhandstelle,” or Trustee Agency, which in the next ten years returned to their owners some sixty thousand “items” representing over a million objects, of which nearly three-quarters went outside Germany. About thirty-five hundred lots were then distributed among German museums and institutes, from which, with proper documentation, it is said, they may still be claimed.

45

If working out these solutions was difficult for the policy makers, the implementation of them, which fell to the MFAA men, was doubly so. For them the problems were human, and their principles and emotions were

constantly challenged as their work revealed some of the least edifying aspects of human nature. These feelings were not diminished by the Nuremberg trials, which began in late 1945. The testimony, in which art figured strongly, provided a dreadful continuo to their discoveries. Nor could anyone remain unaffected by the corrupt atmosphere of the immediate postwar years in Germany, where the fallacies of the plan to suppress the economy soon became apparent. The cigarette became the accepted currency everywhere. For a few Camels one could buy anything from a Rembrandt to a cabbage, depending on the need of the seller. People lied and schemed to find work and sustenance. The food situation continued to be so bad that one office even sent a formal memo to its MP detachment authorizing a German employee to go through the canteen garbage cans. The letters of MFAA personnel are full of pleas for shipments of soap and food from home for German acquaintances, who would invite them to little parties, hoping that they would appear with something edible, which of course they did.

The Monuments men found some solace in time spent on an aspect of their mission which had been neglected in the first frenetic months: the revival of a non-Nazi cultural milieu in Germany. They put on concerts and exhibitions. Seldom have museum directors had such a choice of objects.

At Wiesbaden, Edith Standen (who succeeded Walter Farmer as director), with unparalleled resources at her disposal, put on a series of shows attended by thousands of Germans. From the outset of his tenure at the Munich Collecting Point, Craig Smyth made plans for its eventual conversion into the art historical institute which it is today. By 1946 special arts liaison officers were brought over to promote cultural revival. Among them was Hellmut Lehmann-Haupt, who in the course of his investigations of the effect of government control on the arts was the first to analyze and classify the records of the SS Ahnenerbe and thereby reveal the extent of Himmler’s “archaeological” activities in Poland and the USSR.

Black humor of a sort was provided by the unabashed claims made on the Military Government by a number of the principal movers of looted art. In the years following their various house arrests, trials, and interrogations, Haberstock, Fischer, Lohse, and even Frau Goering asked for favors and claimed works taken from them, which were, in fact, scrupulously returned if legal title could be proved. The Reichsmarschall’s wife appeared in Collecting Point director Lane Faison’s office in April 1951, hoping to recover a small Flemish fifteenth-century

Madonna

which she insisted had been given to her, and not to her husband, by the city of Cologne. She was not humble. Faison’s diary records that she arrived “in a snazzy flat black derby … a spirited Brünnhilde. Put on a good show.

Denied agreeing to put part of Goering pictures on market (via Haberstock and Wildenstein firm) in return for help in her de-Nazification.” Her claim was not pursued.

46

Haberstock, who by 1951 was reported to have set up shop in Munich near the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, and to have reestablished his contacts with his prewar trading cronies in Paris,

47

was seemingly so worried about his reputation that he wrote to Janet Flanner at

The New Yorker

to complain about inaccuracies in her description of his wartime operations in a series of articles she had written on the looting process. He did not deny having traded for the Führer, but complained that she had said he drove a Mercedes when in fact it had been a Ford.

48

Later he wrote to Ardelia Hall at the State Department proposing that she investigate the theft of some books by U.S. Army personnel which might “injure the reputation of the Army abroad, but which could be cleared up within the scope of your activity,” and offering to provide their names. Miss Hall declined his noble assistance, replying that “the case had already been investigated with no result.”

49

Other books

Insatiable by Jenika Snow

Dark Thief (The Two Sides of Me Book 2) by Garcia, Amy Lynn

Blood Sinister by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles

It's No Picnic by Kenneth E. Myers

Dying to Survive by Rachael Keogh

Mortal Friends by Jane Stanton Hitchcock

The House of Grey- Volume 1 by Earl, Collin

The White Amah by Massey, Ann

Teague by Juliana Stone

All I Believe by Alexa Land