The Rape of Europa (77 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Two days after the Strasbourg delivery the first paintings went back to Paris. These were more or less the same ones, mostly Rothschild property, which had left on Goering’s first train, plus the Mannheimer paintings taken at the last minute from France. The Americans had hoped for a little ceremony in Paris, but the French quickly put the shipment in storage

until more owners could be represented. In October, Holland received the Koenigs/van Beuningen Rubenses, the Rathenau Rembrandt

Self-Portrait

, a large number of Goudstikker works, and Goering’s fake Vermeer. Craig Smyth escorted them, and their arrival was celebrated by an unprecedented lunch in the Rembrandt room of the Rijksmuseum. The Dutch, going all out, set the tables with china, silver, and glass from the museum’s magnificent collections and served the astonished guests an elegant meal of oysters, plover’s eggs, and venison. They were not showing off: little other food was available in the strictly rationed Dutch markets.

7

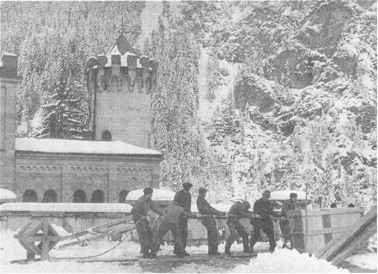

Neuschwanstein reluctantly gives up its treasures.

After these initial “technicolor” returns, things became less elegant. The shipments “in bulk” were to begin from Neuschwanstein. LaFarge put Edward Adams, an American Quartermaster Corps major, in charge and informed him that he would have to live off the land when it came to labor and materials. As art expert Adams had with him a charming but distinctly unmilitary French officer, Hubert de Bry, an authority on eighteenth-century French painting. At the castle some six thousand items plus the office files and papers of the ERR waited to be moved down winding staircases and across snowy terraces to the trucks far below. The only distraction to serious work was a large collection of erotica confiscated by the

ERR, stacked up in a central hallway. The first train of twenty-two cars laden with 634 cases left after two weeks; by December 2, a month later, all identifiable French works in the castle had been returned to Paris.

8

While this was going on, the Munich Collecting Point was shipping out as many as twelve carloads a week filled with every conceivable type of object. Wanda Landowska’s clavichord and Chopin piano, found in a German officers’ club, went home to Paris. The Czernin Vermeer, defiantly protected from removal to America, was hand-carried back to Vienna by Andrew Ritchie, chief of MFAA for Austria. (Ritchie locked himself in a sleeping compartment with the picture and a splendid picnic of pheasant and Burgundy supplied by a French colleague.) From the impregnable bunkers of Nuremberg the Holy Roman regalia also were to go back to Vienna by train. The operation was shrouded in secrecy in order to prevent any revival of Germanic nationalism. When workers were unable to get the huge box containing the silk coronation robe (which had to be packed flat in order to prevent damage) into the special steel boxcar assigned for the trip, Ritchie was forced to commandeer a C-47. Headquarters, always impressed when it came to crown jewels, gave him the same pilot who had flown Goering to Nuremberg for his trial.

9

The Veit Stoss altar, also in Nuremberg, did not go back quite as expeditiously as Eisenhower had hoped. The large figures were blocked in the bunkers by tons of other stored items and could not be extracted for some months. Moving them and certain other Polish treasures, including the

Lady with the Ermine

, would require a train of no less than twenty-seven cars. By the time all this had been arranged it was April 1946, and all too clear that the Polish government-in-exile would not be returned to power anytime soon. The “government of national unity” agreed upon at Potsdam was dominated by Soviet-backed Communists who would not necessarily welcome the publicity generated by the return of the altar by the U.S. Army. But orders were orders and official trips into the Eastern nations precious few, so that the basic party of MP detail and escort officer grew into a large group which included a number of reporters and several ladies. Only Captain Lesley, the MFAA officer responsible for the works of art, had exactly the right travel documents; nor had anyone consulted the American embassy in Warsaw about the delivery.

The train set out from Nuremberg on April 28. As Lesley reported later:

No more inept time of year for the return could possibly have been chosen. The arrival of Poland’s supreme treasures, brought by the U.S. Army as a gesture of democratic friendliness, happened to coincide with the workers’ celebration on the First of May and the Polish

National Independence Day, the third of May. The altar, and all persons connected with it, thus immediately became unwittingly a focus for demonstrations of solidarity and resistance against the incumbent government. The presence of U.S. personnel who, at the same time, gave the people of Cracow an opportunity to connect their emotional reverence toward the national shrine with democratic procedures was exquisitely embarrassing to the authorities in the U.S. Embassy.

10

At first it was all sweetness and light. The train was greeted at the Polish frontier by cultural officials. At Katowice the station was filled with singing choirs sent from the Catholic schools. In Tunel children completely decorated the train with green boughs and Polish representative Estreicher hung Polish and American flags on the sides of the cars. The platform at Cracow was lavishly decorated in the same manner. There was an honor guard, and a band played as the altar was greeted by the City President and the Archbishop. At each stop there were flowery speeches of gratitude for the American effort. On May 1 the American delegation toured Cracow Castle and even reviewed the May Day parade. But the next day the entire group, MPs and all, was suddenly whisked off for an out-of-town overnight tour. When they got back they found that thirty people had been shot in demonstrations during the Polish National Day parade.

Nonetheless, the program to celebrate the return of the altar, scheduled for May 5, was not cancelled. But access to the welcoming Mass and the vicinity of the Church of Our Lady was forbidden to the public and the lunch following was boycotted by the Archbishop. The event was even less comfortable for the Americans, who had been informed in the middle of the previous night that one of their enlisted men had shot two members of the Polish Communist militia and that an investigation was in progress. All American personnel were ordered back to the train, which was scheduled to leave the next day. The Poles produced a number of witnesses who went to the train and identified a Private Bagley as the culprit. When his fellow soldiers gave him an alibi, the Poles produced more “witnesses,” surrounded the train with armed guards, and refused to let it leave until Bagley was surrendered to them. Meanwhile, to the consternation of U.S. embassy officials who had been called in, the irregularity of almost everyone’s travel documents had been revealed. The escort party’s status was illegal and the embassy could not help them.

In the midst of all this, another MP, Private Vivian, came forward and confessed that he, and not Bagley, had fired his pistol at several men who had tried to rob him. This godsend provided the embassy with a Machiavellian

solution to the tense situation. Bagley, “with the most unselfish and commendable fortitude,” agreed to be handed over to the Polish secret police so that the train could depart. Once the train was under way, Vivian “confessed” and was “arrested.” This information was transmitted back to Poland along with a request for Bagley’s release. The Cold War being young, this extraordinarily risky maneuver worked; one can only hope that Private Bagley got a medal.

Karol Estreicher welcomes Leonardo’s

Lady with the Ermine

home.

A few years later the Poles made up for this graceless incident. John Nicholas Brown, visiting Cracow, was taken to a Mass at the Church of Our Lady, where the magnificent altarpiece had been reinstalled in all its glory. His escort was Karol Estreicher. After the service they went to a nearby workers’ restaurant for lunch. When Estreicher told the assembled crowd, which included the priest who had said Mass, that Brown had been responsible for the return of the altar, they all cheered and made much of him. Brown could not know then that the charming and grateful priest would later become Pope John Paul II.

Once the trainloads and truckloads had arrived back in the countries from which they had been removed, it was up to the various national committees

to decide to whom the contents belonged. In France the Commission de Récupération Artistique, organized in September 1944 and officially authorized in November, included Jacques Jaujard, Rose Valland, René Huyghe, and other familiar figures, and was directed by Albert Henraux, vice president of the Conseil des Musées Nationaux. It was most suitably housed at first in the Jeu de Paume. In a pattern followed by Holland and Belgium, the Commission would receive and identify the works, but leave actual restitution to agencies of the Foreign and Finance Ministries, the principal one in France being the Office de Biens et Intérêts Privés, or OBIP.

As soon as the existence of the Commission was made public a deluge of claims poured in from residents of France and refugees all over the world who had had no news of their possessions for years. Letters and cables of reassurance went out as soon as was possible to those whose collections were known to be intact. Maurice de Rothschild, staying in Toronto, was amazed to hear that many of his things were at Latreyne in the Dordogne. But for others the problem was far more difficult. The rub was proof of ownership. The works were stored in the Jeu de Paume and in various warehouses where one was faced with a bewildering array of paintings or furniture. Certain other Rothschilds felt so much at a loss that they hastily summoned their old family retainers, “who seized their bicycles and soon were at the scene like truffle hounds, accurately placing each object. ‘That’s the Vermeer

[The Astronomer]

from the Baronne Edouard’s dressing room’ and so on,” they would remind their employers.

11

Other owners, less well served, found the process more daunting. Mr. and Mrs. Hans Arnhold came back from New York to salvage what they could of the things they had brought to Paris from Germany in the thirties. Mrs. Arnhold was so undone by her first visit to the dusty warehouse of furniture that she never returned. At the Jeu de Paume they found a few pictures, but much, including six large eighteenth-century portraits of Prussian royalty, was simply not there. In the following years they recovered a few more belongings quite by chance. Mrs. Arnhold saw a mother-of-pearl box, inlaid with the family’s initials, in a Paris antique dealer’s window. Some of the furniture turned up at a Zurich dealer; these pieces they simply bought back.

12

Thousands of other families, refugees and château owners alike, whose works of art had gone to dealers or been removed not by the major Nazi looting agencies but by the neighbors, soldiers, or persons unknown, were not even this lucky; they recovered nothing at all.

If the retrieval of lost objects held at the official repositories was a painful task, the tracing of those dispersed through the trade was even

more so, and not to be undertaken by the fainthearted. The articles had generally passed through multiple jurisdictions, and the new owners were and are not always willing to relinquish them even in the face of overwhelming evidence. No case illustrates these difficulties better than the decades-long struggle of Paul Rosenberg and his heirs, whose possessions reposed not only in France and Germany but also in the neutral country of Switzerland.

Rosenberg started his quest very early on. He had lost more than four hundred pictures from both his private and business holdings. In July 1942 he sent a list of the paintings he had been forced to leave in France to the U.S. Customs authorities. In 1944, as soon as communication with France became possible, Rosenberg, in long letters to his brother Edmond, who had remained in France, tried to catch up on four years of family news and business. From Edmond, Paul heard details of the dispersal of his pictures and learned that his house and offices in Paris had been stripped and requisitioned by the Nazis. He was prepared for a long fight and asked Edmond to present his first claims to the Commission de Récupération.

Other books

Pushkin Hills by Sergei Dovlatov

Unleashed by Shadows (By Moonlight Book 10) by Nancy Gideon

Selected Prose of Heinrich Von Kleist by Heinrich von Kleist

Something Special, Something Rare by Black Inc.

The Book of the Dead by Carriger, Gail, Cornell, Paul, Hill, Will, Headley, Maria Dahvana, Bullington, Jesse, Tanzer, Molly

Voyage of the Fox Rider by Dennis L. McKiernan

Mother Daughter Me by Katie Hafner

Buried Evidence by Nancy Taylor Rosenberg

The Safe House by Nicci French