The Ride of My Life (15 page)

While we shopped, he painted for me in broad strokes his vision of what would need to be fixed before the Sprocket Jockeys were ready for the big leagues of state fair demos. First, he went into a tirade about firing Dennis for his cocky attitude. “That McCoy kid is trouble,” he insisted, not really going into details. Then Scura suggested I issue Steve the ultimatum to chop off his hair or hit the road. At that point I knew his ideas and mine were going to clash, but I finished the trade show and we shook a few hands, then I returned to Oklahoma. A few days later Scura called me.

I listened as he laid out his plans for reworking the Sprocket Jockeys show routine to include more choreography, a whimsical cops-and-robbers-style chase scene, and a part of the show where I’d purposely crash so I could rise up and lip-synch to the hit tune, “Broken Wings.”

Give me Fugazi, Dag Nasty, or a little Public Enemy. But I could not merge my riding with Mr. Mister music.

“Let me get this straight, Brian,” I said. “You want me to

crash

my bike on purpose, in a show?”

“Trust me,” he said. “They’ll love it.”

There was no way.

“This is

show

manship,” Scura started to get defensive about it. I explained to him the only show I was interested in creating would revolve around the talent I’d developed riding my bike. No gimmicks, no singing, no cops and robbers. I’d go big, build up to my hardest tricks, and ride my best. Period. That’s the business I wanted to be in.

There was a long pause and I could sense the gears whirling in his head. Finally, in a cold tone, he told me, “You’re never goin’ anywhere with that attitude, Hoffman,” and hung up on me.

I cracked up.

We needed a semi. The C-60 truck just didn’t have the horsepower to pull the portable halfpipe. At sixty miles per hour, the ramp created considerable drag and was essentially a giant parachute. The C-60 would dog out and wheeze up the slightest hill or headwind, unable to cut the mustard. Steve and I found a diesel truck headhunter, who tracked down rigs for sale around the country. Since nobody would sell a semi truck to a seventeen-year-old in the state of Oklahoma, we had to go out of state. After some searching, we got a line on a flat-nosed Peterbilt cab over a 350 Cummins diesel engine, out in the boondocks of Kansas. Steve and I hopped a flight, then took a taxi down a dirt road to a farmer/trucker’s house. I knocked on the door with a $12,500 cashier’s check in my hand, a smile on my face, and no idea how to start the thing. Much less a license to drive it.

“Son, you do know how to drive a semi, don’t you?” was the first thing the owner of the truck asked, skeptically. The inside of the cab was a wall of buttons, knobs, and levers. My eyes glazed over. I assured the guy I was a quick learner. We started the truck up, and it rumbled like thunder. Steve and I drove off in first gear, waving to him out the window. We kept driving down the dirt road and most of the way to the highway in first—first gear tops out at five miles an hour.

It takes a certain rhythm, and an ear for the right rpm whine, to know when to shift a truck through her sixteen gears. After the low gears, you don’t use the hydrostatic clutch, you just throw the stickshift and let off the gas pedal for second. Your body gets in tune with the road speed, engine vibrations of the truck and you just sense when it’s time to upshift or downshift. It’s almost like playing chords on a giant instrument—when you don’t get it into gear right away the music turns into the most incredible,

unsettling, jolting metal-grinding sound. It’s the ultimate penalty buzzer. Steve and I had shifting figured out by the time we arrived home a few hours later. Unfortunately, we smoked the clutch to a crisp during our training session.

The first order of business was to get the rig outfitted with a booming stereo. It got a fresh paint job next, which we did ourselves with the help of our friend Davin “Psycho” Hallford, an expert at art and fire. Soon there were lacquered flames curling down the side of the truck and trailer. And of course, we got us a CB. My handle: Condor. Steve’s: Bull. The cab had a sleeper section, but it was pretty grim, like a metal prison cell on wheels. The bunk stank like a public toilet and featured the comfort of a thin mattress.

However, nothing was more punishing than having to ride in the Mephistopheles Mortuary. The Mortuary was a small room at the front of the trailer, which I originally envisioned as a rider’s lounge or a recreation room. I wanted the Sprocket Jockeys to have a plush air-conditioned oasis with a little TV set, a couch, a shag carpet, and a minifridge stocked with snacks. I envisioned it as the cushiest place on the road. Unfortunately, I never got around to making it highway-friendly. It was pitch dark inside, and hot as hell in the day and freezing at night. It was unprotected from the engine sounds, the road vibrations, and the constant howling of wind. The springs and shocks on the truck were heavy duty enough to haul a hundred thousand pounds of iron, but not designed for the pleasure of soft humans. It rattled so badly inside the Mortuary that if you were lying down on the couch, you would often catch two or three feet of air at random and get slammed to the floor in total darkness. Any time there were more than four guys on the road, it meant somebody had to ride in the Mortuary. If you drew the short straw and had to ride in back, you would be on your own for a few hours because there was no way to communicate with the people in the cab of the truck. The Mortuary smelled like diesel fumes and other fluids the truck would periodically leak, and, technically, it was illegal to ride back there.

The legalities of operating a big rig were a bit of a grey area for the Sprocket Jockeys. I honestly tried to get a semi driver’s license, the legal route, and passed the state’s written exam but failed the driving part. I never quite got around to retaking the test. Besides, it was illegal for me to drive the semi outside of Oklahoma under the age of eighteen anyway. Steve eventually got his CDL license, and when he turned twenty-one he could take us anywhere in the country. Being up to code was on our list of concerns, it was just never that high a priority Our mantra became “Avoid Authority.” We learned to switch drivers at sixty-five miles per hour. We bought the special trucker maps with the interstate weigh stations clearly marked, so we could take alternate routes. We couldn’t afford to pay fines.

The weigh station inspectors seemed to take pleasure in giving us a hard time. The rig looked like a carnival ride, which had bad reputations for causing highway accidents. We didn’t have four seat belts in the cab, and the truck typically had at least one mechanical violation. The inspectors always hassled us for narcotics. Searches could take hours. At a weigh station in the Bible Belt, after being detained for a while and repeatedly asked where we kept our weapons or drugs, the inspector asked Dennis McCoy, “Do you have any weapons in your possession?” Keeping a straight face, Dennis held up his fists and said, “Just these.” The inspector’s mood shifted from grumpy to irate, and we ended up spending about three hours getting searched for nonexistent contraband.

If there was no other way around the weigh station, I’d pull in and they’d shut me down and tell me I had to get a licensed driver to move my rig. I’d hang out until they closed down their booth for the day and then sneak out. Once, we came up fast on a checkpoint in Mississippi and there was no way around it, no way we would pass inspection, and we were in a hurry. I blazed past the station and kept the semi pointed straight down the highway. Minutes later a wildy gesturing man in a white truck with an orange light and Department of Transportation insignia on his doors had pulled up alongside us, yelling, and pointing, and carrying on. Steve and I pretended not to see him, which made the guy even madder. We debated pulling over and just decided the guy didn’t look like enough of an authority figure to get us in

real

trouble. So I put the pedal to the metal and drove on. He gave chase for another few miles, and finally we crossed the state line and left our pursuer in his own jurisdiction. The weigh stations were a pain in the ass, but these were actually the least of our concerns with the semi.

We would roll into remote truck stops in the dead of the night in a rig with flames and names painted down the sides, and a pack of freaky, longhaired, tattooed, shit-talking joke-cracking kids would stumble out and proceed to act goofy. It attracted the stares and glares from the seasoned road veterans we encountered. I started to work on my Oklahoma accent, letting it thicken up nice and hicklike. I peppered my convo with plenty of hellfire and swear words and grew sideburns and shaved them in the shape of lightning bolts. I got an “American by Birth, Trucker by Choice” solid pewter belt buckle

and had the word “Condor” branded into the leather across the back of the belt. I also practiced the lost art of spitting, and even though I didn’t dip tobacco, I could fake it so real nobody knew the difference. I also figured out the best way around trouble was total denial.

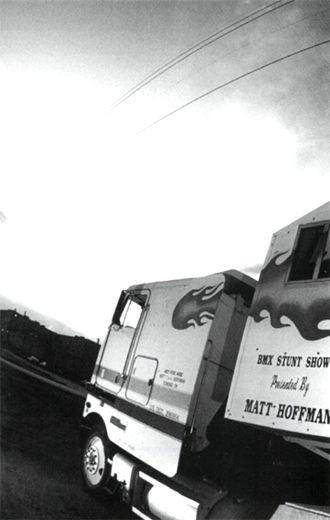

Redesigned with a fresh new paint job. I did a wall ride on it to christen it. (Photograph courtesy of Spike Jonze]

“Are you the crazies who jump them bikes on the U-Track?” fellow truckers would ask with an ominous tone, confused about what to call the halfpipe.

“Hell, no. We just drive the damn rig around for the crazies,” became the standard reply. I could talk the talk, and after visiting a few hundred truck stops, I was gradually accepted into the trucker family.

At first it was the coolest feeling to settle down in the Naugahyde booth of a truck stop diner, macking in the elite “Professional Drivers Only” section. Then we realized how many truckers are also chain smokers and got a peek at the menu: chicken-fried this, country-fried that, deep battered with a side of butter covered in homemade savory gravy. Truckers are not the healthiest group of guys on the planet. Sometimes we’d pull into a truck stop at four in the morning, blind tired, and find truckers packed in the video game room, bleary-eyed and hands vibrating with two cigarettes going at once, a supertanker-sized jug of coffee at their side, pumping quarters into a

driving

video game. I couldn’t figure if they were warming up, or coming down. Steve’s vice was chewing ice cubes to stay awake, and I discovered the black magic of coffee. I’d talk rapid-fire and he’d have a numbed mushmouth effect going as we cranked Operation Ivy and Minor Threat, and rumbled down the interstate. It was like a punk rock, trucker buddy movie.

The Sprocket Jockeys started landing shows in states as far away as Texas, Virginia, Florida, Washington, and Michigan, and close calls became more frequent. One time we were driving to a show and the trailer got a flat, then another flat, then all three wheels on one side had blown out. I couldn’t tell the difference behind the wheel, the 350 Cummins was unstoppable and would go seventy miles per hour, no matter what. We dragged the trailer like a giant steel sled, metal melting onto concrete for who knows how long. Finally some frantic motorist got my attention and I casually glanced in the side mirror to see a twenty-foot-tall rooster tail of sparks showering behind the truck, causing cars to swerve and traffic to hold back behind our Peterbilt powder keg. I started laughing hysterically as I pulled over to the side to sort out the mess.

Keeping the semi running was a constant game of duct tape fixes and shoestring budgets. The first priority was always putting money into paying the Sprocket Jockeys and making sure the riders were taken care of. Rarely was there leftover cash. The truck seemed to know exactly how much money I had on me and would break down and need exactly that amount for repairs. People would sometimes ram their cars into the truck to collect on insurance. There was one situation involving high speed and a low bridge—I hit an overpass and knocked the ramp off the trailer into the highway. Steve and I had to retrieve ramp hunks from the fast lane of the freeway, like

Frogger

only while dragging giant sheets of metal and plywood. We got the ramp almost entirely out of the road and some guy in a station wagon hit the last piece and got a flat. The police made us pay for his tires on the spot, and then two months later we got an invoice from his insurance company for a $3,000 transmission.