The Ride of My Life (33 page)

The next time I got on my bike, I had to struggle to clear five feet of air. I was being mellow, trying to get acclimated to the feel of my bike moving underneath me. It was so foreign. It gave me a whole new respect for bikers. I couldn’t believe how much I’d taken my skills for granted when I was at the top of my game. Now those skills were gone. I played around, sticking to lip tricks until my brakes slipped on a Canadian nosepick. I dropped to the bottom like a dot-com stock. When my leg hit the ramp, my lower leg sheared off and rode up my femur, completely tearing my ACL. I couldn’t believe it. I wondered,

again

, if this was it for my days as a biker.

February 1999. I decided I wasn’t ready to give up yet. After crashing the Canadian pick and trashing my cadaver components, I became desperate for a way to fix my knee. I’d need another operation just to walk, so I figured I might as well research every alternative treatment done on ACL/PCL replacement. Thank God for the Internet. I found hope in the form of synthetic ligament replacement procedures. Just as quickly, I ran into a brick wall in the United States, because the FDA refused to sanction synthetics, citing that it wasn’t a long-term option. By even giving me advice on how to get the procedure done elsewhere, a doctor practicing in the United States would put their medical license in jeopardy. It’s funny how you think you own your body, yet the government really has control over us in so many ways. Dr. Yates knew the deal, though, and was very helpful in steering me in the right direction for plastic parts: France. Their top orthopedic doctors had been successfully doing ACL repair on rugby players using a thing called the LARS ligament. These guys were back on the field after only four weeks—my previous surgery took me out for six months.

I started sending faxes and E-mails to French doctors with unpronounceable names.

I narrowed it down to two options. I could go to France to have the surgery done, or go to the French province of Montreal, in Canada. I chose Canada for its socialized medicine. The prices were right, only about $5,000 for the entire operation. It ended up going down like a drug deal on

Miami Vice

. I had to go alone, and bring cash, and pay the doctor in my hotel room the day before. The downside was, they wanted me to be a human guinea pig. They were doing research on the operation and wanted to prove it could be done without extensive anesthetics, which are the most dangerous part of any surgery By proving it was possible to do the surgery without anesthetics, they could promote it as a safe alternative to ACL reconstruction, increasing their odds of being sanctioned by the FDA.

The procedure called for them to open up my knee and drill a six-millimeter hole down the length of my femur. The drill bit was fifteen inches long. I would be fully conscious and have no pain medication for the surgery. In fact, I could watch close on three TV monitors in the room.

It was kind of like an interactive horror movie. My skin was numbed with a local anesthesia, and then the doctors brought out the drill. “We haven’t figured out a way to numb the inside of the bone, so this will hurt,” my doctor said to me. It hit bone and the room filled with a smell that, well, I don’t think you ever want to get a whiff of your own bones smoking. The drill surged and grunted onward, the tiny motor straining as the pain began to increase. Then the tip broke though into the marrow. My heart rate was supposed to stay below eighty beats per minute, and it shot through the roof when

I felt the hot drill strike the soft marrow inside my femur. It was pain taken to a new level. On a scale from one to ten, the knobs turned to an eleven-kind of painful. It didn’t help matters to actually see what bone marrow looks like; spongy red and yellowish pulp, like corned beef hash. I had to struggle and concentrate on my breathing to get my heart rate down, while squeezing the steel rails of the bed with my hands as tightly as I could. Every once in a while the nurse would lean over and say in broken Franglish, “You doing real well, Mot.” This went on for the longest thirty minutes of my life. Once there were holes in my femur and tibia, the doctors threaded a polyester ligament through the bony tunnels. Basically, they put a ski rope where my ACL once was.

Afterward I was sewn up and I sat up on the table. There was an awkward pause as the doctor snapped off his latex gloves. I’d just had major surgery, without drugs. “Am I free to go?” I asked, my mind reeling and unsure of what to do. “Yep,” said the doctor. We shook hands and I limped from the surgical table to go outside and flag down a cab.

I finally got a cab and crumpled into the backseat, marveling at the incredible strangeness of life. Ten minutes ago there were six hands shoving tools and titanium screws inside my knee, and suddenly I was in some dirty shoebox of a taxi, hustling back to my hotel. I kept thinking I was doing something wrong; there was very little postoperative pampering and nurturing going on. At the hotel, I fell in bed and flipped on the TV. I settled in for what would become a forty-eight hour pay-per-view marathon, starting with the buddy cop comedy

Rush Hour

, subtitled in French. Before long I had to use the bathroom and faced my first crisis; I couldn’t walk and had no crutches. I got two chairs under my arms and used them to

slowly

crab across the room to the beckoning toilet. It was a painful, sluggish struggle.

On the third day I got in a cab to the airport, boarded my flight, and went home a new man, with a new knee, and a new lease on life.

When I’m too injured to skydive or do anything physically active, my guitar is my passive therapy solution. (Photograph courtesy of GG)

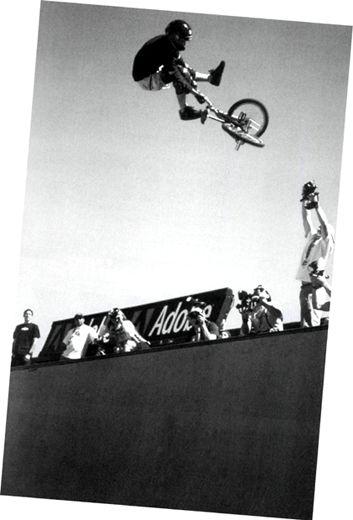

I broke two metacarpals in my foot, so I had to rig a makeshift cast at the 1996 X Games. To make my shoe stiff enough to ride with, I pounded a steel spike down the sole of my shoe and carved an insole out of masonite. It was a pretty interesting comp.

May 1999. The LARS ligament healed up clean and quick, and I was back on my bike in a month. I rode and grew stronger, clearing my brain of business troubles by carving around on the halfpipe. Before long I was eyeing a line that had been calling me for over a year: a big transfer from the vert ramp to the street course. It was during a casual session at the Hoffman Bikes Christmas party, when I decided to give myself a present: the gap. I launched and pulled the highest backflip I could over it, and in my enthusiasm, overrotated. I was wearing a knee brace and still managed to dislocate my knee on impact. The synthetic ligament was ripped out of my femur, and I was back to square one. I didn’t know what to do and felt totally defeated. It was another black day at Hoffman Bikes.

I sent a letter to the doctor in Canada who did the LARS surgery, and he said it would have been really hard to break the synthetic ligament; they were supposed to last at least five years. Dr. Yates did an exploratory surgery and found the ligament wasn’t broken, I’d just yanked it out where it was anchored into my femur. He reattached it with a better procedure, implanting a little more titanium into my body. Two weeks later I had a fully functioning right knee again.

But I didn’t hop back on my bike immediately. I’d just been through a frightening two years, plagued by knee problems, and I wanted to be mentally ready for what came next. I didn’t want to rush out and push myself in a race to get back my chops. It was also a tough time to make this decision. The sport was bigger than it had ever been, and it was the most lucrative time to compete in the pro vert class. You could make $10,000 for a flawless two minutes on the ramp. I was staging events, running a company to pay back my debts, and watching everyone prosper.

I’d pushed the boundaries throughout my career and knew there were other things I still wanted to do on my bike. But I couldn’t expect my body to keep up with my mind, without ending back up in the hospital. I wanted to go in a new direction entirely—one that was a challenge, but also without expectations. I took my brakes off, to rediscover my bike under the new terms I was dealt. I didn’t know what was possible on a bike without brakes, and it was like a new sport. At one point I stripped my bike down to just the essentials: a frame, fork, bars, crankset, and wheels. Just to see what I could do with that. I was in my own world. I went back to the beginning, to the rewards that got me interested in the first place. Just riding. Not competing, not endorsing, nothing else but discovering what I could do with my bike and my body. I wasn’t in a class anymore.

People ask me if all this trauma and suffering was worth it. I’ve invented over one hundred original ramp tricks. I can roll in and catch fifteen feet of air without pedaling. I’ve felt the rush of taking off my hands during 540s spun eleven feet out. I’ve jumped my bike off the edge of a thirty-two-hundred-foot cliff. I’ve shot up a ramp to see what the ground looks like from fifty feet above it and rode away from peril. I’ve ridden for crowds of screaming people, eighty thousand strong. And I’ve ridden by myself where the only sound was my breath and my tires singing on plywood for hours on end, when there was no else left to ride with.

None of it would have ever happened if I thought the pain and suffering it would take to ride my bike and follow my heart wasn’t worth it. If you want to experience life’s pleasures, you have to be willing to take all the pain and failures.

I love what I do. No regrets.

TESTIMONIAL

PROVING IT

Once you know a trick is possible, it’s a little bit easier. Nowadays you have foam pits and resi mats to help you take that next step, learning tricks on vert. Even if you don’t have the foam, it’s easier to learn it once you’ve seen it being done. Mat blazed the trail with the flip fakie. The flair. The endless different combo variations. He was the guy who took variations like tailwhips very high. I can think of a lot of instances where Mat was the one to do something big and gnarly. He took the slams for everybody else to learn a trick. He was the guy that found out what was possible.

--DENNIS MCCOY, PRO RIDER

Doing a tailwhip during practice at the 2000 X Games. Media frenzy.

“CAN I HAVE YOUR AUTOGRAPH?”

Popularity is a trip. One that comes with a lot of extra baggage.

I grew up thinking bike riders were untouchable superhero-demigods. When I was twelve, my friends and I devoured every page of the BMX magazines (there were no videos in those days, and bikes were never on TV). We were under the spell of the twenty-inch bike industry-marketing machine—an industry that was small potatoes back then. To overcompensate for its limited size, the industry barraged its fan base with visual cues that pimped the dream. Pages were packed with action snapshots and advertisements. The images oozed with an undercurrent of success, fame, and glamour: hotshot pros throwing tabletops over top-end automobiles; sweaty gladiators brandishing giant cardboard victory checks, getting mobbed by hundreds of kids after winning a national event.