The Ride of My Life (30 page)

I finally got a window of opportunity to B.A.S.E. jump in January of 1997. Actually, it was more like a peephole of opportunity. I was doing a vert demo at the Superdome in New Orleans, Louisiana—the same Cajun metropolis where John Vincent happens to reside. Immediately after the bike demo I was scheduled to make a trip to Colorado to see a shoulder specialist at the Steadman-Hawkins clinic. I needed to get my arm working again and knew I would be out of commission for a while after the surgeries. I was aching to do one last gnarly thing to hold me over during recovery time. The day after the demo we awoke with the chickens, five-thirty in the morning, and hot-wired an elevator. Our goal was to get to the top of a fifteen hundred-foot-tall steel antenna on the edge of town. This structure transmitted Soft Rock Hits of the Seventies and other radio signals to the good folk of Louisiana. I was going to jump off it.

John generously loaned me his favorite chute. I was so driven to get this jump in that I actually talked my friend Bryan—who was completely terrified of heights—into helping pull off the caper. His role was to accompany me up the tower, not look down, and capture the moment on tape. The crucial three-chip digital video documentation was not so much for my glory reel—it was so I could study my technique and learn everything I could from my actions.

It was supercold, and we all had bed head and bad breath. The service elevator carried us up about a hundred feet and it froze. Try as we might, the thing wouldn’t climb another foot. In retrospect this was probably a good omen. I was getting frustrated, excited, and desperate to get a jump in before I went under the knife again. My mind was so focused on jumping that there was no way I was backing down. I hadn’t taken

into consideration that John’s rig was set up for B.O.B. (Bottom of Bag) deployment chute. My rotator cuff was so jacked up, and my shoulder was barely functional, so the reach and jerk technique needed for this type of deployment would have been extra hairy. My arm could have slipped out of its socket and I wouldn’t have been able to get the chute open. I was being stupid, and even the best jumpers are smart and humble enough to back down on occasion. Thinking back on that moment, I feel fortunate the elevator denied us the opportunity to reach the exit point.

But John knew of a bridge. It was two hundred and seventy feet tall and spanned the Mississippi River, just across town. “

Hell,

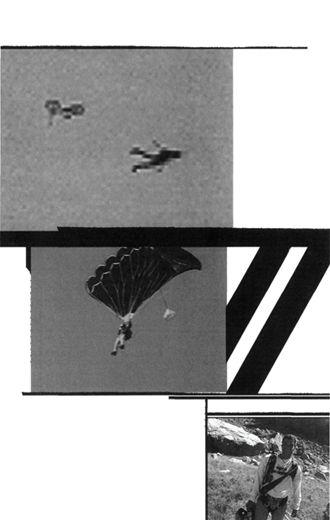

yeah,” I said. It was decided that for this short height I’d need to do a Hop-N-Pop, a technique in which you throw your pilot chute the second after your feet leave the ledge. I climbed up the concrete beast like an eager little tick, ready to suck on some life. The wind was gusting, and to add to the list of weather hazards, it started sleeting. I figured out the wind was going perpendicular to the river, which meant I didn’t have to worry so much about being flung back into a bridge pillar or support buttress by a rogue blast of air. If anything, it was gonna blow me away from shore. I looked out over the surging brown waters of the Mississippi, with cold air filling my lungs. I had about eighty skydives in my logbook. I’d been practicing, I had my track down, had my on-heading openings down, landings down, everything. I knew if I waited for my upcoming surgeries to heal it would be four months. As I was up on the apex, psyching myself up and preparing to drop, a squad car was scoping out Bryan on the ground. Bridge, river, guy with video camera, and at seven thirty in the morning. What’s wrong with this picture?

When you jump, it’s like committing suicide but not dying. Even though you trust in your rig and your capabilities, it takes a moment of pure conscious decision to get yourself over the edge. You have to fly the Fuck It Flag and just… go. I leaped, got a brief taste of intense ground rush, and popped open. The wind made short work of me, and pulled me out over the water. I splashed down in the dirty, swiftly moving currents and went under. My winter clothes and a helmet were heavy, but the parachute was the real problem. A parachute works by creating lots of drag, even underwater. It was going to drown me if I didn’t get it off, pronto. I felt guilty because it was John’s, and not only expensive but, more important, it had a personal value that was irreplaceable. He’d done about five hundred hectic jumps with it, and it had never let him down. I swam for shore and crawled out soaked to the core and shivering. I ran, trying to beat the currents carrying the parachute down river. There was a dock nearby where tugboats operated, accessible via a nearby building. The door was locked but shaky, so I gave it a few swift kicks. I whipped out two wet $20 bills and passed them off to Steve, who was on our ground crew. Through chattering teeth, I asked him to hire a tugboat captain for a rescue mission to retrieve John’s chute. I turned around to make my way back to John and Bryan, when I heard someone approaching from behind me.

“Son, what’re you doin’? Are you stupid?” the voice of authority said to me as I sat in the back of the patrol car, cuffed. I was dripping bilge water everywhere, mildly hypothermic, had just replaced my surgery recovery time with a jail sentence, and I was worried about John’s gear. “Yeah, I’m not arguing with you officer. I feel pretty damn stupid right now.” The cop began running my name for a warrant check and noticed my Oklahoma driver’s license. “Boy, what the hell are you doing down here in Louisiana?” Dejectedly and absentmindedly, I muttered that I was in town doing a bike show. The cop stopped and brightened up. A smile cracked under his moustache. “At the Superdome? Were you the one doing the flip?” The demo I’d done was indeed at a monster truck show in the Superdome. “Yeah! That was me all right!” I said, trying to sound chummy. The cop said his kids loved my show. In two minutes the entire situation was reversed—I was unarrested, and the city supervisors en route to press charges had been radioed and talked out of it. The cop gave me his card and told me to send a photo of the day’s jump and advised me not to try it so damn early next time. Roger that, officer.

When a human being falling at one hundred and sixty miles per hour collides with a jagged pile of granite, it’s really bad. Your skeleton comes out of your body. All the organs, cavities, and sacs of fluid inside explode. Everything hard—bones, teeth, the spirit—shatters like glass. It has to be a terrible way to go, supereded by probably the purest, most alive, mind-blowing twenty-second ride possible.

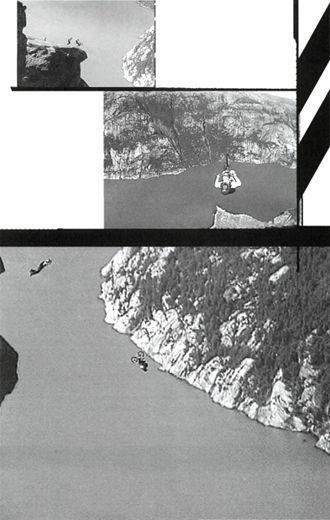

John and I had been trying to find a way to combine bike riding with skydiving. We wanted to cook up a rush that would burn for months inside our hearts. He said he knew a place, a Norwegian cliff top B.A.S.E. jump hot spot called Kjerag. At thirty-two hundred feet tall, the exit point is higher than both the World Trade Center Twin Towers were, combined. And you could ride a bike right off the edge. Unforgettable, but also brutally unforgiving. A razor-sharp, diamond-hard shelf of rock extends from the cliff and creates a severe hazard about twelve seconds down. Jumpers have to use maximum caution and track far enough from the cliff face to clear this ledge. “I will figure out a way to get us there,” I told John. I started making phone calls.

In late June of 1997 Kjerag attracted the attention of accomplished skydiver Stina-Ulla Ostberg. Stina had twenty-five hundred skydives to her credit, but Kjerag was unlike anything she had ever attempted. Sources say she failed to heed local experts’ advice about the dangers of the shelf. At the twelve-second mark, Stina realized she wasn’t going to clear the rocks and threw her pilot chute. Seven-tenths of a second later she impacted and was killed instantly.

This was my fourth B.A.S.E. jump. There are no words to justify the intensity yet peaceful feeling these jumps create. It was beautiful.

I rolled into town eight days later. My shoe sponsor, Boks, was footing the bill, but John and I were on a simple mission: Get in, get off, get out. I brought Steve for support, and a camera crew of our friends Shon and Morgan to document. We stayed in the nearby village of Lysebotn, in a hostel. The most lavish expense on the trip was beer, which cost eight bucks apiece for cheap stuff. We were at the ends of the earth, down the fjords and up the mountain and in the middle of nowhere. But Lysebotn was infamous. B.A.S.E. jumpers from around the world were attracted to the cliff like moths to a flame. There was a community of jumpers who lived in the shadow of Kjerag, hiking up and hucking off as often as possible. The exit point was discovered and jumped for the first time in 1994 by Stein Edvardsen. He was one of the local masters and the go-to guy if you intended to jump. Because of the recent death of Stina and a series of other tragedies on the mountain, the Lysebotn locals were extra critical of who was jumping. They were assessing skill levels and strongly discouraging amateur attempts. They didn’t want thrill-crazy tourists pillaging their playground and spilling blood on the rocks because of inexperience and stupidity. With John’s help and B.A.S.E. jump street cred, I got the nod from Stein, who was a bit wary that this would be my second B.A.S.E. jump ever. I told him I was definitely an amateur jumper but ready to absorb any advice he had about successes and failures. I was humbled by what we were about to do, yet driven to do it. I wouldn’t have traveled halfway around the world to Kjerag if I thought

maybe

I could make it. This was a stunt I’d spent seven years building up to; all the split-second life-death skydiving skills and tests would be put to use. Stein poured me a cup of tea and calmly said I’d need to listen to him carefully if I didn’t want to die.

It took close to four hours to get to the top and earn our fun. We chugged along, swearing and joking, gasping for breath as the incline turned our legs to putty. Craggy boulders and rushing mountain creeks were crossed, the path put us through pockets of dirty summer snow and fields of mossy green lichen. With the Norwegian sun shining twenty hours a day, its rays bounced off the granite and made the ground sparkle like jewels.

We arrived at the peak and got a look over the rim; it took my breath away with its staggering beauty and sick vertical drop. Just seeing the bottom of the void felt powerful. Way down below, the icy waters of the fjord rippled with wind, and gray rocks the size of tract homes dotted the shoreline where the landing area lay waiting for us. It was less than a minute away via the Kjerag express route.

It never left my mind that a thing this gorgeous could also end my life, but my focus was needed elsewhere. I took a few moments to get into the mental state of 100 percent concentration on what I was about to do, my pulse racing and my mouth dry. Time to live. John and I exited together. Four seconds after my feet left the cliff I was doing one hundred miles an hour in a headlong dive bomb; my biggest concern was the critical factor of clearing the ledge. Because my rotator cuff on my

right shoulder was unpredictable, I was throwing my pilot chute left-handed for the first time ever. I was also wearing John’s rig. Both of these factors increased the odds of a screwup, but I was in control and feeling great. My altitude awareness was sharp, and I held on for a few more seconds as I milked the ground rush of my life, then deployed my chute with about five hundred feet of air to spare. I made a landing as adrenaline charged my blood with electricity.

We hiked and jumped a second time that day. I asked John if I should attempt a double gainer off the exit point. “Sure, why not,” he said, confident and casual.

The drop from the exit point gave me twelve seconds before I’d reached the jagged outcropping in the cliff face that had killed Stina, and it took a six-second lateral track away from the cliff wall to clear the outcropping. That gave me six seconds to complete two flips, six seconds to track away from the wall, and after I’d cleared the outcropping, I could drop another six seconds before having to open my chute. When calculating these details, I realized the numbers involved were 6-6-6. Weird.

I ran off the cliff and threw a backflip, getting an upside-down glimpse of the cliff wall blurring by just a few feet from my head. I could hear it whistling past, the spookiest sound in the world. John had jumped just a second behind me, wearing a helmet cam. I saw him above as I came around on the second flip. Then it was time to get my delta track in place, get out past the ledge, and pop the chute.