The Ride of My Life (27 page)

As was often the case, I’d be out of town or overseas doing demos. Steve and Jay would be dispatched to drive the semi truck to the fair shows. Sometimes they spent weeks on the road, packed into the cab of that Peterbilt. The lifestyle of a Sprocket Jockey was a demanding one, and over time, the close friendship Steve and Jay shared began to unravel. To complicate matters, Jay had the metabolism of a field mouse, and we could only afford to pay him $15 per diem. I’ve seen him consume $60 worth of food a day [we’re talking road grub, too—not spendy New York steakhouse fare], and he’d still be famished. And if Jay’s daily caloric intake was insufficient, he’d get hypoglycemic and a scary transformation would occur. We called this personality phenomenon Larry. When Larry made an appearance, hotel rooms got trashed, swearing was rampant, and destruction reigned over everything. Nobody was fond of Larry. After a grueling tour and months of stress, Steve and Jay were getting along like two cats trapped under a laundry basket. In a Texas hotel room, Jay announced he was quitting the team; Steve agreed it was probably best for all. Later that evening, psychotic Larry made a confrontational midnight entrance. There was urine involved. Push came to shove, and Steve, blind as a mole without his glasses, got clocked in the head.

Jay was gone the next day.

He got picked up by Schwinn, one of the bike industry giants who had a spotty track record when it came to supporting the sport—but they had money and were gearing up to build a new BMX and freestyle team. I was glad Jay got the sponsorship opportunity he’d been searching for, and after hearing about Larry and Steve’s hotel room showdown, knew it was time for Jay to move on from the HB family. I wasn’t that stoked Jay took the bike design we’d been working on with him. We built a beer bottle opener into the frame near the seat mast. It was supposed to be his signature frame. The design carried over to his new Schwinn model, minus the bottle opener. But whatever.

When Dave Mirra wanted a pay hike, it also came at a time when every extra cent we generated was already going to my team riders; I couldn’t afford to cough up much more. I was already paying Dave

$1,000 a month when he came to me and asked my advice—he had an offer from Haro on the table. I told Dave I could maybe go up to $1,250 a month, but even that was really out of my league. Haro was bidding $1,500. But I didn’t want to forfeit to Haro by $250—if I was going to lose a good rider and friend, I wanted to lose big. I told Dave to tell Haro I was paying him $2,500 a month, but also said that if Haro didn’t try to top that fictitious salary, I wasn’t going to be able to swing it. It was shady, but Dave was up for it. Haro bought the story and “matched” his salary of $2,500 a month. I was bummed to see him go but happy that I’d helped boost his starting wage—Dave deserved every dollar he earned, and he quickly proved himself a valuable asset to Haro’s team roster.

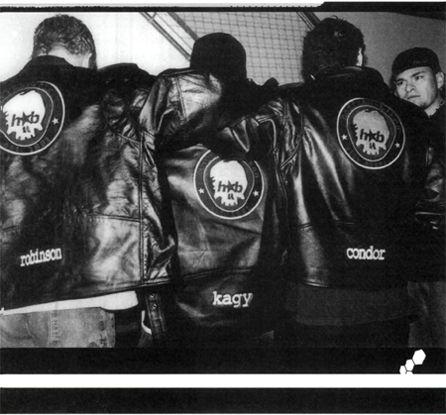

Kevin Robinson, Chad Kagy, and me. I’d just given everybody on the Hoffman Bikes team new leather jackets.

The formula for success at Hoffman Bikes has always been to find people I could trust, who were ambitious and energetic, and empower them with all the tools they needed to kick ass. Finding trained, groomed workers was never as important as finding the people who had the passion and were willing to commit to the cause. I’ve picked up an incredible staff using this hiring approach.

The second full-time salaried employee I brought on board after Steve was a guy whose real name, for the longest time, I didn’t even know. I called him Chuck. Chuck was a pale, freckled, red-haired guy who stopped by to ride with us at the Ninja Ramp—he lived out in the boonies and we didn’t see him around often. Chuck found out about our plans to start a company, around the same time we got the BS series off the ground. Chuck offered to help us put on our second BS comp, which was in Arizona. We didn’t know the kid too well but figured, what the hell, free labor. We left Oklahoma on Route 40, one of the longest, driest, most boring, desolate highways in the United States. Just a couple of miles into our twenty-hour minivan journey, Chuck got violently ill. Steve and I exchanged, “Aw man, who

is

this knucklehead?” glances as our volunteer bent over on the side of the road, heaving his guts out. It was going to be a

looong

weekend. Since I’d already experienced the nauseous joy of putting on and riding in a BS contest while extremely sick, I had no desire to repeat the experience. I told Chuck to stay a couple seats behind me in the van. We frequently pulled over to the side, with the hazards flashing, while Chuck got his heave on. Between bouts of vomiting, he asked me why I kept calling him Chuck. I didn’t want to tell him it was because I’d forgotten his real name (which I later found out was Mark Owen). I’d come up with Chuck because he reminded me of a red-headed kid in school who used to beat me up. However, I didn’t tell him this, either—I told him it was because he bore a striking resemblance to Chuck D of Public Enemy. “Oh, okay,” Chuck said and folded back in half to let loose another roaring torrent of regurgitated Burger King Whopper slop.

Chuck proved himself at the Arizona BS contest. By the time the comp was over and Chuck’s bout with food poisoning had passed, Steve and I knew he was employee material. He was cheap, worked hard, rode bikes, and understood what we were trying to do: change the world. Chuck moved in with Steve and began working at HB as a jack-of-all-trades. When he started, he couldn’t turn on a computer—he went on to become our in-house bike designer. He taught himself computer-aided drafting (CAD], learned to source materials at machine shops, and eventually became the guy who oversees all bike production. I call him the “I can do Anything” guy, because that’s what he’s capable of. Chuck also volunteered to work at every single contest we held and gradually became known to us as Mark Owen. If you’ve ever been to a BS contest, you have to give it up for Chuck. I mean Mark.

Other guys from our Edmond riding posse, like Page Hussey and the Collins brothers—Mike and Chris—came into the fold and made vital contributions, too. None of the friends I hired had much training in the jobs they would eventually master and excel at, but they were highly resourceful. They lived the lifestyle of 100 percent riders and action addicts. The ramp park in the back of the warehouse attracted people from all across the country, and sometimes this plywood playground acted like a Venus flytrap, snaring many potential victims … I mean, employees. Street pro Keith Treanor came to ride the park and ended up working with us for a spell. And there was a helpful Hawaiian named Big Island who had a trustworthy face—he was tapped to handle the cash-box at the door and the sign-up table at BS contests. Eventually I stuck Big in front of a souped-up Mac and we discovered he had skills as a designer. I could use all the help I could get in the art department—the graphics for the first batch of Hoffman Bikes were press-on letters from the art section of the local Kinkos, which looked like it spelled “Condo” instead of Condor. I enlisted the aid of HB team rider and artist Davin “Pyscho” Hallford to help craft better logos and also found a guy named Bryan Baxter working at Massive Graphics, my T-shirt print shop. Bryan rode, played music, and was an artist, so I had to steal him to work at HB. He was our first art director, and when we started doing video production and websites, he took over that territory Big and Chris Collins became the new art department regime and began designing ads and art directing the materials. With a Web presence, slick titles and video production, and good graphics on our stuff, the HB image smoothed out and started looking pretty pro.

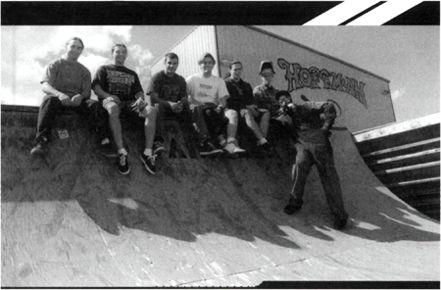

HB in effect, circa 1993. Team rider Jay Miron; vice president Steve Swope; me; head engineer Chris Gack; TIG welders Shane and Paul Murray; and our do-everything guy, Mark Owen.

Sales were super, but after four years in business we were spinning our wheels. To grow and keep up with the demand, we’d need to expand into the territory claimed by the well-distributed manufacturers like GT, Haro, and Schwinn. In short, we’d need to take our bike line from strictly hardcore vert, street, and flatland fare into the realm of budget bikes. The idea was that since most bikes sold are entry-level rides, we could get new kids into riding, gain presence in our shops, and once the shops saw how fast the low-budget models moved off the floor, they’d order some of the more serious equipment.

Building an economical bike couldn’t be done with our in-house machine shop—we were cranking out product as fast as we could get raw tubing on the shipping dock, but it was walking a razor’s edge just to stay afloat. To cut the margins and try to make things cheaper would sink us for sure. The key was to source a competent manufacturer in Taiwan, where the prices were more affordable. But even setting up that program cost a lot of money, because the Taiwanese factories had minimum orders and needed down payments before they would do a production run. Mike Devitt, my old friend from SE, mentioned the T-word to me and I brushed it off, saying I couldn’t come up with the down payment money. Mike suggested I get a letter of credit from a bank and that would work as a cash advance for Taiwanese companies. I had a better idea. I got my international distributor accounts to preorder and send me letters of credit from

their

banks. I sent these letters to my Taiwanese manufacturer to finance my order. Whatever profit I made from these preorders I used to finance additional bikes for me to stock. It was a way of covering the fact that I had no money, and to my surprise, it worked. With the profit I made from selling these bikes, I was able to order an additional container. So, for no money out of pocket, I got two-for-the-price-of-none and was able to bring a new bike to the Hoffman lineup. It looked like a rare occasion where math was working in my favor.

We called our first Taiwanese bike The Egg, because we just knew they were built to crack. The geometry and componentry were okay, but the frame and fork sets, compared with the heavy-duty Condors, were merely high-tensile steel tubing. It had an affordable price of just $199.99. Perfect for the beginning rider for transportation to school and back. Unfortunately, our reputation preceded us, and despite our best efforts to alert bike shops that The Egg was

not

the same style bike as our infamous American built, high-end, high-performance lineup, a lot of the hardcore riders bought Eggs. They tried to jump them, street ride them, take them on vert, and literally scrambled the Eggs. We got back tons of cracked frames and choppered fork sets; it was clear we had to do something before our reputation was destroyed. The Egg sold out but cost Hoffman Bikes a chunk of credibility. I knew we couldn’t make the same mistake twice and had to find a better way to get bikes made in volume.

Taiwanese manufacturers had machinery I would drool over. With their equipment

they could build more consistent bikes than what I could do in my shop. They just needed somebody looking over their shoulders, to make sure everything was done to our specifications. With the help of a friend in the industry, we found an agent to help us find the cream of the crop in Taiwanese manufacturers. Our agent could source a shop to build anything we needed and would make sure it got done the way we wanted. I would also send Mark Owen over there to peek in and make sure they didn’t cut any corners. With the new system, a complete bike was not coming from one company but several smaller and medium-sized facilities: the tire guys, the seat guys, the crankset guys, the handlebar guys, and so forth. We just cut a check, and several weeks later the finished product arrived at our warehouse. We had a dependable lineup of small Taiwanese shops staffed by craftsmen who could create the bike we wanted to meet the demands of the hardcore riders and could make lower-end units, too. It took a ton of pressure off of us back in Oklahoma. I wound down the in-house machine shop and phased out the headaches of running a massive staff.

One of my favorite things about owning a company is I got to name the bikes. I decided my fat cat, George, was too awesome to not have something named in his honor. The Hoffman Bikes George model was questioned by a lot of shops because it sounded like a stupid name for a bike, but most of the Georges sold. One day my agent in Taiwan called me at home to notify me that the tire company that was developing our new line of tires could put a signature or fancy name embossed on the sidewalls of the tires. She wanted to know if I wanted

Condor

on there or if I had any other ideas. George had just crapped on the stairs at home. “Hmm,” I said, staring at George’s steaming mess on the white shag, as he dragged his ass across the carpet as toilet paper. “How about Skidmarks?” Six weeks later the first batch of Skidmarks tires arrived on U.S. shores, and they’ve been Hoffman Bikes’ standard tires ever since.