The Ride of My Life (22 page)

The last thing I needed was to ride that thing in front of a lot of people, under pressure. It was enough of a head-trip just facing the big ramp. I wanted to ride it for myself, by myself, when the time was right. If I had some fire in me that day, I could go get it out by riding the ramp, but it took Steve to pull me. I could talk him into it, and trusted him with my life, but knew that he didn’t always like what he was doing. He didn’t want it on his conscience that he’d towed me toward my own demise. I decided to build a ramp I wouldn’t have to rely on anyone to ride. I began plans to turn the quarterpipe into a halfpipe.

It took two years of planning and saving before construction on the world’s tallest halfpipe was nearly finished. To pump a twenty-foot-tall tranny, I’d need speed. Tons of it. Without motorcycle assistance, the next best thing would be a giant roll-in, like the takeoff for a ski jump. I went with a forty-six-foot-tall platform that shot me into the ramp at a sixty-degree angle. The halfpipe took two months to build and, like its predecessor, was also a winter construction project. One night when I was close to completion, I could see the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. I was out there alone. It was mid-January and just after midnight. All I had to do was get the first layer of plywood on the roll-in. I didn’t have a deck built on that side of the ramp yet, and the roll-in connected to the roof of my old warehouse. I made my way up the roll-in, laying down one piece of ply at a time. I’d nail a short block of two by four sideways into the transition, to act as a step, while I attached the next piece of plywood up the ramp. Finally I’d gotten every sheet on except the last piece, which needed to bend sharply at the top of the roll-in. As I tried to get the plywood properly positioned, it popped off and began tipping sideways. I got out of the way and watched it slide down the ramp. The

wood acted like a wedge, knifing under the top block of my wooden stairway to heaven. The block popped out with a chunking sound, then the sheet dropped down to the next step. Cachunk! And the next… chunk! Chunk! Chunk! Cachunk! Chunkchucnkchunkchunk! I stood at the top of the roll-in and stared down at nothing but nails sticking out where the blocks had been. It looked like a runway of golf spikes, all the way down the sixty-degree wooden slope. I sat there for a while, dazed and thinking how in the hell something like that could happen with such flawless, total destruction. Then it dawned on me that I was stuck at the top of a forty-six-foot-tall structure and the only way down was to slide through a field of nails. I could wait until morning, when people would show up for work, and they could get me down. That was in eight hours.

Twenty minutes passed, and I was freezing. It was windy, and I’d stopped working, so my body temperature was dropping. I knew I’d be a Popsicle if I waited much longer. I stood there, no foot planks, looking down the barrel of the roll-in until I felt the

Geronimo!

instinct kick in. Because of the cold, I had on superthick Carharrt workpants and four layers of clothes, I went down the slide and the nails ripped my clothes to shreds. I got to the bottom, breathing fast, pant legs in tatters, and thought, “All right, we’ll call that a night.”

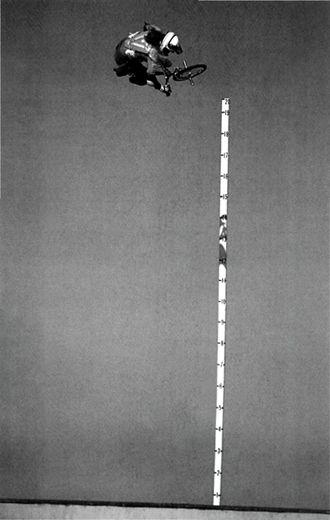

When the ramp was all finished, I stood on top of the roll-in with my bike. I could clearly see downtown Oklahoma City, ten miles away. The halfpipe resembled a giant boat. The stomach-floating effect of taking the roll-in was the same sensation as bungee jumping. I could drop in and clear eighteen feet on the first wall.

The only problem was, my bike was too small—the wheel base was three feet, and the twenty-inch wheels would quickly reach their maximum velocity. After my first air, the transitions would slowly bleed my speed no matter how much energy I put into pumping the walls. I went from eighteen feet, to fifteen feet, to thirteen feet. I’d need another solution besides the roll-in.

This was the photo Mark Losey shot for the cover of

BMX Plus!

It was the third incarnation

of giant ramp, and the first time I rode it after I lost my spleen on the half-pipe. (Photograph courtesy of Mark Losey)

People sometimes ask me how I can stand living in Oklahoma, when the riding scenes seem to thrive in other places like California, Texas, or pockets of the East Coast. I’ve always let the space in my brain exist as its own environment. My body might be in Oklahoma, but my mind’s been someplace else the whole time. I’ve never really needed to subscribe to another social circle. I always had a ramp, I had a family, and I had weird projects running around in my head. All I need is a place to let them out. Oklahoma has been the cheapest laboratory I could find. For the record, Oklahoma is also probably the best place in the entire world to convert a bike to run on a reverse-engineered weedeater engine. Nobody involved ever questioned the ridiculousness of it. The general attitude was, “Yeah, that sounds cool, man. Let’s get it on. “After some research into various motor types, I bought the biggest weedeater I could get. My friend John owned Road and Track, a local performance motorcycle shop. With John’s help, I repositioned the points so the little engine would run backward, driving my rear sprocket. We machined a drive shaft for it, welded motor mounts to the frame, and duct taped the gas tank on. I had to use a tiny 13-tooth sprocket on my front, and a 122-tooth freewheel. There was no chain, so I tightened my cranks and pedals in place. We set up the throttle cable through my Gyro, so I could spin the bars and keep the throttle cable from tangling. After completion, I’d set up on the roll-in, grab the throttle and dive into the ramp with the engine whining at seventy-two hundred rotations per minute, full speed. The first airs were in the nineteen- to twenty-foot range. The bike had a weird gyroscopic effect in the air, and the engine, fuel, and extra metal on board put the center of gravity way off to one side. My back end would lag every time. It’s also weird getting used to the timing of a bike that doesn’t naturally decelerate; I’d reenter the ramp with the throttle fully cranked and have to let off before the opposite wall. What I was doing lost a lot of the elements an aerial has; on normal twelve-foot airs you can look over your shoulder and see the coping as you start steering the bike toward reentry. On twenty-foot plus airs, I would go fast and launch straight up like a missile, and try to turn around after I’d slowed down at the peak height. I had to wait until the bike has stopped upward momentum, and if my timing was off, I didn’t turn. I fell.

It took a few sessions, but I got used to it, and began working up until I was clocking airs in the twenty-three- and twenty-four-foot range. Then

MTV

Sports called and asked if I was working on anything new.

Maybe it was karma’s way of getting back at me for taking advantage of the deal on heavily discounted wood in Kansas City, but the bill was about to arrive. MTV sent a skeleton crew of two guys, a producer/sound operator, and a camera man. They were in town for only two days. The first day was too windy to get high airs, and the next day it was gusting about twelve miles per hour. Any wind speed above five miles per hour made it really difficult to ride the big ramp because the higher altitude seemed to magnify the wind many times over. Having a weird bike with a weedeater engine didn’t make it easier. But I wanted to show them what I could do on the thing, and so I rode anyway. We taped for a few minutes, and the airs were getting higher, consistently over twenty feet. Then I missed my timing on one and didn’t rotate enough. I went from rocket to rock.

I tried to keep my head from hitting the ramp and took the force of the blow with my ribs. I saw stars, but didn’t get KOed. Sometimes when you hit that hard your body just starts throbbing, but you can’t really diagnose what’s wrong. You have to chill out and let everything settle down and figure out if you need to go to the hospital. I got up and walked it off, pretty shaken, and went inside the warehouse to relax a little bit.

We watched the crash on video, and it didn’t look that bad. I knew I’d slammed harder, even on smaller ramps. This was a smack-n-slide crash. My midsection got it pretty good, but I also caught quite a bit of the fat transition, which helped lessen the impact. What I didn’t know was what was happening inside my body. I’d been beating on my spleen all year, taking crashes in shows and practices. The organ was in a constantly swollen state, and the impact from over twenty feet was enough to burst it. We were still talking about filming more high airs when I noticed my collarbones began to ache. I hadn’t taken much of the fall on my arms or shoulders, and I couldn’t figure out why they were throbbing. It was pressure from blood hemorrhaging inside my abdominal cavity. Before long I began to get dizzy. On the way to the water cooler, I leaned against a wall for balance, and the floor rushed up to greet me. Steve, my girlfriend Jaci, and the film crew knew this was not a good sign. I was only out for a few seconds, because as soon as my body got in a horizontal position my heart could generate enough pressure to get blood moving to my head.

The paramedics were called, and a few minutes later, when they arrived, I was worse. I’d passed out again from trying to stand up, and people were starting to get that crisis situation panic about them. The paramedic put a blood pressure cuff on me and took my pulse. He said it didn’t register but told me not to worry because his medical gear had been malfunctioning earlier. Steve asked about internal injuries, and the paramedic told him I’d have bruising and discoloration, from the blood pooling inside. I didn’t. As I lay flat on my back, the medic tried his blood pressure cuff and got a weak pulse. I didn’t have $500 for the ride to the hospital, and my health insurance was a shake of the dice, regarding what they’d cover and what they wouldn’t. We told the ambulance to go away, and Steve and Jaci brought me in.

You turn into a mumbling, happy fool when you are about to die. And you don’t care. The human body is amazing the way it heals itself, reacts to trauma, or prepares to shut down. Your pituitary gland unleashes a flood of endorphins, which takes the edge off anything and calms you down. Pain, stress, and fear start to melt away. “I need my keys,” I slurred to Steve as they tried to get me in the backseat of the car. “Don’t let me forget my keys.” I was talking gibberish; what I needed was a surgeon. En route to the hospital I was mad because Jaci wouldn’t let me go to sleep. The ER doctor examined me and told Steve I’d need an emergency spleenectomy to save my life. Inside, my ruined spleen was leaking massive amounts of blood—I had lost four pints. He said another twenty minutes and I wouldn’t make it.

A spleenectomy is one of the crazier abdominal surgical procedures. The doctors remove all thirty-something feet of your intestines and put them in a bowl next to you while they mop up the blood and remove chunks of broken spleen floating around inside you. Your spleen produces white blood cells, which helps your immune system fight off infections. But it’s also somewhat of a bonus organ. Your body doesn’t need a spleen to keep on living. After the ruptured spleen is cleaned out, the doctors check your intestines for holes by hand, like looking for a flat tire in a bike inner tube. The surgery takes a couple hours, and the recovery time is pretty fast thanks to modern medical techniques.

The first thing I saw when I woke up was the MTV producer. I’d just had my colon fondled from the inside, could barely open my eyes, my brain was spaced out on anesthesia, and my whole torso was throbbing from the trauma. “Hey, Mat. I know this is a bad time, but, could you sign this, ah, liability release form for us?” I couldn’t even hold a pen. I tried waving him off by mumbling that I accepted full responsibility and would never sue anybody for something I did on my own. He said his job was on the line, because he’d forgotten to get a signature before we started filming. I signed the paper and haven’t worked with MTV or attended any of their sporting events since.

We all want something nobody can take away. A personal mark that stands for a time when you did your best. I believe this desire is inside everyone. It’s there the day you are born—your true calling. It takes experiencing life to reveal that purpose. You have to realize your potential, then challenge it. You must give everything you’ve got to get there. If it were easy, it wouldn’t mean so much. By accepting whatever consequences may arise, you’re free from having to worry about getting validation from others, or permission. Approval or failures don’t matter. All that matters is that you pursue what you have inside you. Once you’re on that mental plane, anything is possible.

I knew my mission was to go higher than anyone. I was willing to break rules, break convention, break my bank account, my body, and whatever else it would take to reach that place. I had already gone about fourteen feet out of a ramp, but I felt there was more. I listened to people who told me a twenty-foot aerial was impossible, and then I listened to my heart tell me that without challenge to what is known, there is no progress.