The Ride of My Life (21 page)

I cleared the Ninja Ramp height pole the first day. This was my victory air. I knew it was going to work.

Masonite is common in a lot of indoor ramp parks. It’s not weather resistant at all. It warps and bubbles if it gets wet. A wet ramp is a slow ramp. Dry, indoor masonite also produces dust when ridden, making the surface slippery. There is typically a dust cloud over a park full of masonite. As a riding surface, masonite is smooth, and better for skaters. It’s also softer than wood. Metal ramps are super-fast but are also slippery when dusty. When the dew hits in the evening, the non-porous surface turns into greased lightning. The other downfall is that metal gets hot as hell in the sun. I’ve seen riders slam on metal and knock themselves out and then get third-degree burns because they cooked to the surface. For the modern era, I think Skatelite is the answer. It’s got the best properties of plywood and masonite in one package: It’s smooth, fast, durable, and not too slick.

Coping is an often-overlooked part of the ramp. The early bike ramps didn’t have coping, so the sharp edges where the deck and transition joined were a leading cause of flat tires. The concept of coping, borrowed from skate ramps, helped reduce pinch flats. Coping also bonks your front tire out so you can time exactly when to pull up for your air. Different types include pool tile, mideighties-style PVC, and the good old two-inch-diameter black steel unthreaded pipe. The two-inch black steel has been the overall winner through the years. Galvanized steel is good and slick but grinds down eventually and gets tacky; then you have to wax it, or you’ll screech to an abrupt halt on peg-to-coping contact. Steve Swope was the first bike rider to do peg grinds on coping, adapted from skateboarding. I was the second guy. When we learned to grind, we switched to metal coping. The ramp at the Paris KOV event in 1988 had the biggest coping I ever rode. It was close to six or eight inches in diameter and was impossible to get a flat on, no matter how hard you hung up.

Halfpipes have decks where the riders wait to drop in for their runs, or do platform or lip tricks. At big comps, there are a lot of distractions from the crowd on the areas of the deck closest to the stands. Decks with ladders or stairs mean lots of photographers and miscellaneous people can climb up top, so riders will also usually roost on the side only accessible by riding up and popping out. Decks are where you breathe, tune out the world, and stay focused on your bike.

The framing and foundation are the skeleton of a ramp. Everything has to fit together perfectly, be totally level, and solid. The less flex a ramp has, the quicker it rides The first quarterpipes required a couple people to stand behind the ramps and brace them, because these gems tended to slide backward when ridden. Ramps that are permanent structures are generally pretty solid and fast.

Temporary ramps built for demos or contests are sometimes assembled hastily or by inexperienced crews, and these can be a nightmare. I’ll ride whatever, but it’s frustrating as hell when people have come to see big airs and the ramp sucks. You just have to deal with it. It’s like someone gave you a zebra instead of a bike and told you to bust an air.

I’ve been on a ramp where someone decided it would be a good idea to attach the two by six cross-braces (the backbone of the ramp] sideways. It flexed so badly the transitions absorbed most of my momentum, and it felt like it was layered in carpet. But the worst ramp I’ve ever ridden was a makeshift number for Club MTV. Downtown Julie Brown could have built it herself; from the broomstick coping, to lack of cross-bracing, to the abruptly kinked three-step transition. I think I could have bunnyhopped over it easier than pulling an air out of it. It was silly, and 100 percent MTV. By contrast, I’ve seen master ramp builder Tim Payne start with a pile of wood in the middle of Shanghai with seven Chinese guys who couldn’t understand a word of English. We had a perfectly built vert halfpipe in seven hours. Don’t ask me how.

Concrete is in a world of its own. It has no competition. Speed, character, durability, texture, and then some. It’s what turns transitions into art. Unfortunately, it also takes a serious commitment to build a concrete riding environment. One of my first experiences riding concrete was a short session at the Upland Pipeline skatepark before it was bulldozed. It was dark and spooky, like a big hole. In the Combi Pool, it was an accomplishment to make it to the top and bonk your front tire on the coping. That half-day I spent there gave me a new respect for the skatepark-era riders and what it took to flow the way Eddie Fiola, Mike Dominguez, Brian Blyther, Hugo Gonzales, Jeff Carrol, and others rode ’em. It was nothing like a halfpipe. It’s a whole different discipline.

The other way to ride cement is to steal your sessions. Backyard pools are fun, because the thrill of the hunt and temporary nature of your session factors in there. When my brother Travis got his pilot license we would rent a plane and fly around neighborhoods with a map and mark down everywhere we’d see an empty pool. Then we’d wait until the owners left for work, and we’d go ride it. We found a semiabandoned pool once that seemed especially ridable. We had to empty it, so we rented a water pump, drained it, and cleaned it out, animal carcasses and all. Within twenty-four hours a bunch of kids threw all the garbage back in, so we cleaned it all out again and rode it. The next day all our tools were gone from our secret stash spot, and the pool was completely filled in with dirt and leveled off. That was the last good local pool I rode.

In the weeks following the Stuntmasters shenanigans, Airtime’s advice about bigger transitions was still ringing in my head. I did some calculations of my own and didn’t like the way things were adding up. The building materials needed to construct a twenty-foot ramp would cost about $7,000, even if I stuck to a slim budget. I didn’t have that kind of cash laying around, especially with the Peterbilt money pit. But Rick Thorne said he had a friend who wanted a Haro frame. A friend who happened to work at a lumber store and was willing to make a shady deal. A few days later, I tested the black market value of a red Haro frame and fork set I had left over from my old sponsor. I rented a U-Haul trailer (the semi was broken) and drove to a Kansas City lumberyard. The scam was, I paid for my order up front, and the crew in the back would load it up for me. (The loading zone guys all rode.) I purchased one 2×4 for four dollars, and the clerk told me to pick up my order at the loading dock. A squad of smiling bikers piled it high with sheet after sheet of 4×8 plywood, hundreds of 2×4s, 2×6s, and 4×4s. It was enough wood to build a house. The weight of the lumber made the trailer droop.

Steve and I had never gotten into anything this big before. We’d built a few ramps in our time, and Steve had worked a couple jobs as a carpenter’s helper, but this was new territory. We cut the first transition, a twenty-foot radius with a foot of vert, and wrestled it upright to check out the standing height of our baby. “Holy shit!” screamed Steve. “That’s taller than a telephone pole, Mat.” He sounded real nervous. I took one look at it and began laughing uncontrollably, like a little kid on Christmas morning.

The ramp put up a fight, but it started coming together piece by piece, day by day. Steve and I built it near my dad’s warehouse on an unused section of the property. The back of the ramp was at the edge of a landfill that had been a dumping ground for scrap iron, cinderblocks, and industrial junk. It was also where the office septic tank seeped into the ground. We cracked it when we were using the bulldozer to level out the area where the ramp sat and the whole area smelled like shit.

We’d spend a few hours each night after work nailing and framing. It was the middle of winter and constantly wet, windy, and cold. The ice-crusted ground gave us a stubborn battle as we dug holes for the four-by-four support pillars, which would provide a solid foundation. The building project took over a month, consuming most of my energy and thoughts. Finally the day arrived when we were hanging off the back of the ramp mounting the last of the decking—minutes from completion. It was pitch dark, twenty degrees, and sleeting, but Steve and I were focused on finishing. Everything was starting to ice up. To reach the top, we had stacked up three sets of scaffolds, and on the uppermost platform we had to put a few cinderblocks and a plank to make an even taller workstation. On the top of that was a chair, which is where I stood. Steve was on the scaffolding, bracing my legs as I whacked away with a framing hammer, trying to get the last sheet of plywood secure without falling thirty feet off the back of the ramp. Steve was so pissed at me. He thought we were being stupid and one of us was going

to fall. But I was superdetermined, and he stayed out of obligation. I probably should have listened to him, but I was beyond reason.

I felt a deep sense of accomplishment when I finally stuck the last nail in the wooden beast. Steve and I built a twenty-foot-wide, twenty-one-foot-tall quarterpipe—the biggest quarterpipe ever made. It was time to air it.

I had to put aside everything I knew about ramps and treat it like a new form of riding. My main concern was if my body could take the G forces when entering the ramp with a sixty-mile-per-hour approach speed. For the first attempts at the ramp, I was towed while holding onto a pickup truck, but the truck couldn’t get up to speed quick enough. Then some guy on a Honda street bike stopped by to see what the hell we were doing. I convinced him to tow me down the dirt path toward the ramp. On my first air, I cleared my previous record of fourteen feet by a foot. I went out looking for a motorcycle to tow me. That same week I found out I’d won “Freestyler of the Year” award by BMX Plus! magazine. The prize was a motorcycle. It was pretty slow street bike. I had it shipped to a local motorcycle shop in Oklahoma City and traded it in for the fastest used dirt bike I could get, a KDX 200. I held a ski rope with one hand and steered my bike with the other as Steve towed me down a two-hundred-yard plywood sidewalk. This process sent me flying out of the quarterpipe over twenty feet.

It felt amazing. The airtime was several seconds of climbing, an exaggerated sensation of stalling out, then reentry. At the peak of my airs I was more than forty feet off the ground, higher than anyone had ever gone on a bicycle. On a normal ramp, at the apex of an air I can see the coping and adjust myself accordingly. On the big ramp, I was too high to see the coping clearly, and my perspective had changed dramatically. I could see the entire building, people on the ground, behind the ramp—stuff that you’d never notice riding a small ramp. It’s a pretty crazy feeling at first. I painted logos on the center of the transition, which became the target to aim for.

Wind was a wild card I had no control over, and the higher I went, the more susceptible I was to being bullied around by air currents. It was a guessing game trying to counteract it, and eventually we started flying a flag on the deck as a wind gauge. The power of the forces at work made themselves apparent one day when I hung up my back wheel on reentry from twenty-one feet out. I was going so fast when I clipped the coping, it ripped the tire off my wheel and wrecked my rim. Luckily I didn’t get hurt, but that was the tipping point for me—the moment it sunk in how serious it was. The impact speed was unreal. Bailing from the twenty-foot range (over forty feet off the ground] had major consequences, which I would soon learn. The fat trannies made it a bit less scary because their huge radius helped absorb some of the velocity, but when I did crash, I’d hit and continue skipping and bouncing across the ground for a long ways, like a puppet hucked out of a car at freeway speed.

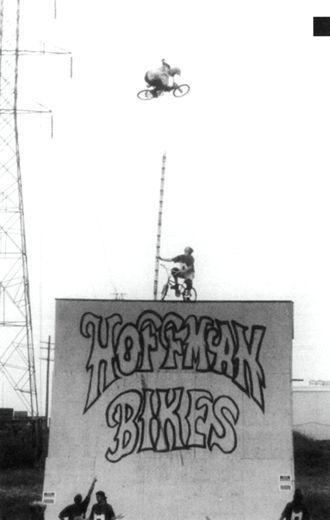

I made the first Hoffman Bikes ad from this photo. I asked the Sprocket Jockeys to run out on the ramp to give it perspective. I had my sister shoot this with my mom’s camera. Little did I know at the time it was published that I would get flack for this image. People thought it was fake.

We kept a lid on the big airs and took some photos for an HB ad. My sister, Gina, shot it. She used my mother’s old camera as a tribute to mom’s strength and passion for life, art, and following your heart. My heart had led me there, in a field with a few friends, testing the boundaries of everything I knew I could do, and what I dreamed I could do. The shot we picked was a boned-out aerial, twenty-one feet over coping, forty-two feet off the ground.

When the ad debuted in the June 1992 issue of

Ride

magazine, there were people who didn’t believe it. Even though I had a reputation for doing high airs, I was also notorious for having a goofy sense of humor. Powerful desktop software like Photoshop had started gaining popularity in print, and eye-popping computerized effects were the latest rage in music videos and movies. The skeptics who saw the ad were critical of digital hoaxes and had a pretty strong argument: What kind of idiot would actually build a twenty-one-foot-tall quarterpipe?