The Ride of My Life (18 page)

Precision materials and craftsmanship came with a steep price tag, and I found out I couldn’t afford to have Linn Kasten’s shop do production. Mike Devitt of SE Racing saved the day. Mike was another old school BMX guy, and he’d been through the ups and downs of the industry with another legendary company, SE. Their machine shop could make a limited run of custom frame and fork sets. The condition was, I had to pay for half the batch up front, the other half on delivery. “Make me two hundred of these,” I told Devitt and sent off the schematic for the Condor with a down payment check for $18,000.

With bikes on the way, I needed employees. Steve didn’t even have to think about it—he was in. We set up offices in the Ninja Ramp warehouse, cobbling together desks and chairs from thrift stores. Steve and I both concurred we’d need a computer or we’d be dead in the water. We bought a new Apple II LC, 80 mhz with about eight megs of RAM, which was state-of-the-art 1992 hardware. As we pulled the Mac out of the box, neither one of us knew how to turn the thing on. I called Brad McDonald, publisher of the newly minted Ride magazine, who seemed to have his act together with computers and desktop publishing. Brad gave me a few phone tips, and Adobe Illustrator was installed. I stayed rooted in front of the screen for twenty hours a day, mousing and clicking, and two weeks later the first Hoffman Bikes product catalog was ready to take to Kinkos to get printed. While out in Los Angeles on a shoot for Dirt magazine, Spike snapped photos for the catalog for free (Spike, thanks again). Steve bought an accounting and inventory program, and he embarked on a crash course, teaching himself operational basics in a series of long nights. We were a company.

A couple months later, the UPS guy rolled up with a truckload of boxes and a big fat C.O.D. invoice. The first batch of Hoffman Condor frame and fork sets had arrived. It was a glorious day. Some were already earmarked as giveaways—I gave a few to deserving riders—but the bulk of the shipment was going to dealers. We stacked the bikes right next to the Ninja Ramp, polished them and slapped on the decals, then reboxed our booty and prepped our orders. In the time we’d waited for the payload of frames to arrive from the machine shop, Steve and I had worked the phones and faked our voices to sound older and more confident. We convinced a few shop owners around the country to carry our product line, which was a feat in itself considering the bleak bike market. Because of the manufacturing costs and high-quality materials, by the time the Condor frame and fork sets were hanging on bike shop walls, they cost around $350. At the time, a budget-minded shopper could pick up a generic, entry-level complete bicycle for around $200. But there were ample numbers of hardcore riders out there willing to shell out the clams, and by some miracle, we sold out of our first run of Condors in one month.

This cycle was repeated as fast as we could afford to rebuy another production run and get the machine shop to fabricate the next batch. It took about six months. In my opinion, that was too damn long to wait for a bike. I felt orders slipping away; I knew if I were a kid with a wad of cash in my pocket, I’d have a hard time waiting half a year to get a new bike. Another problem we had involved juggling the money—we’d bring in cash from doing demos or touring with the Sprocket Jockeys, but the semi literally burned cash every time we turned the key in the ignition. In addition, although most of our bike shop accounts were pretty honest, there were a few rubber check writers out there. Accumulating the down payment dough to set SE’s machine shop into motion on our bikes involved a substantial amount of scraping, saving, truth-bending, and creative financing. A bank loan was out of the question—they wouldn’t give me the time of day. I was a dropout with an eighth-grade education and no manufacturing experience. Furthering my anxiety, I had a feeling sometimes the SE guys would stop in the middle of a run and work on another company’s production jobs. Delays eat into timelines, and it was frustrating. Steve and I knew from the interest we’d had with our bike shop accounts, we could sell everything we could make. We just had to supply the demand, pronto. My solution to this economic mayhem: Dig the hole even deeper.

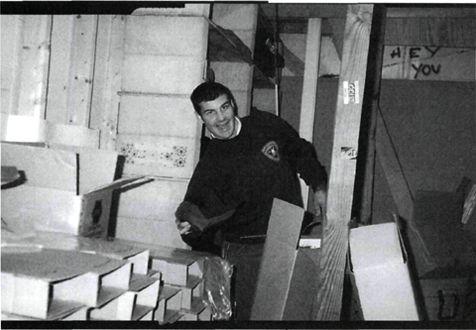

Packing orders under the deck of the vert ramp. We were always crowded for space.

I went to the Small Business Administration (SBA) and met a lady named Susan Urbach. I expected her to give the “you want to do what?” corporate laugh, but I thought I’d ask her advice about getting a manufacturing facility set up. She told me I needed a business plan, gave me some books, and told me how to put one together for her. I studied the materials, figured out what a business plan meant, and submitted mine to the SBA. It ended up securing us a $40,000 loan to get our operation up and running. We began checking out just how to buy all the machinery needed to start building bikes.

“Y’all want to start a machine shop, eh?” clucked the guy from the local vo-tech center. “How much money you got?” He sounded skeptical, eyeing our long hair and young faces. Steve and I relayed the good news, that we had forty grand. The guy, whom we’d come to for advice as a shop foreman, said there was no way to get all the equipment needed to cut, grind, weld, bend, drill, mill, and polish metal for forty. He said it was going to take two hundred and fifty grand, and that was for a no-frills machine shop. He chuckled again and suggested we come back when I’d saved up for another few years. I told him we had forty, so we’d just have to make that work. We thanked him for his time and bought a newspaper that contained classified ads for industrial equipment.

The critical step in our grand scheme was to lure a seasoned shop foreman to help us. There was a guy who fit the bill named Gack. He was from California and had training and technical skills in bike building. Gack was an accomplished rider, which was the main bonus as I looked over his résumé. We lured him out to Oklahoma, and with his help we sourced the tools and raw materials for our products. Through persistence and wild deal-making, we’d found all the machines we’d need to turn tubing into gold. The only machine we had to improvise on was the one that bent round tubing into an ovalized shape for the down tubes of our frames. The real version of the machine was tens of thousands of dollars. Steve, Gack, and I figured out how to get similar results using two flat steel plates and a car jack, carefully smashing the tubing until it looked oval. It was rigged to duplicate the same shape—we may have been sketchy, but dammit, we were consistent.

Within a year we quadrupled production capacity, paid back the loan, and won the SBA’s Young Entrepreneur of the Year award. The machine shop became our lab, enabling us to tinker around with our designs to enhance performance at will. We built frames for flatland, dirt, and street, but perfecting designs one frame at a time was only part of the picture. We needed to crank out a prolific volume of product and do it in time to make the trade show dates and retail schedules of the industry. It was going to take manpower. If sourcing the right tools to form a machine shop was mildly traumatic, finding the folks to operate those tools was an ongoing nightmare.

The bulk of the work was not that technical, or dangerous. It was boring. Local journeymen and metal workers all wanted $25 an hour, even for repetitive tasks like

pulling a lever three hundred times a day. That hourly rate was too spendy for us, so we turned to the only other option available—the unemployment office. We staffed up with a crew of ex-cons, slackers, sketchers, grifters, and various types of human driftwood. There was a high turnaround of employees, and we quickly discovered that a favorite scam of the terminally unemployed involved working for just long enough to collect benefits, then quitting for a relaxing vacation paid by the state. However, even the hassles associated with finding trustworthy employees were a piece of cake compared with the ongoing management issues we dealt with on a daily basis.

Polishing chrome-moly before it was chrome plated was the worst job in the building. Our resident expert was a salty-looking forty-year-old dude with dreadlocks. He was perpetually covered in a thick layer of dust from the polishing booth, but the guy was good at his job and never complained. He was on the rebound after a stint in prison, and you could tell he’d lived a grizzled life. I considered him one of our better employees—he showed up on time, put in a reasonably good effort each day, and he was entertaining. He constantly communicated in rhymes, and every sentence that flowed out of his mouth sparkled with the lyrical quality of a professional orator. His only flaw: The man was addicted to nicotine. I hated to come down on the guy, but after several months on the job his smoke breaks were getting longer and more frequent. It was beginning to cut into our production schedule, and a quarter of his day or more was spent on smoke breaks. I was informed to include a “yellow slip” in his pay envelope—which was the work performance evaluation paperwork that ensured if I had to let an employee go for work inadequacies, I didn’t get stuck paying their unemployment benefits. The little yellow slip in this instance basically asked my polisher in a nice and professional way to cut down on the Camels and increase the work output. The guy got his paycheck and must have assumed we wanted to can him, or he really took his cigs seriously. He asked to borrow twenty dollars for a carton, which I loaned him, and then he said a rhyme and cha-cha-cha’ed out the door. We never saw him again.

On occasion, it was not a matter of keeping employees but getting rid of them. Once, I’d traded a pair of Airwalk shoes for a printout of a major manufacturer’s entire customer database—about a hundred thousand names. The mailing list was huge, and valuable, but the info needed to be typed into a computer before we’d really be able to capitalize on it. Steve and I both sucked at typing, so we hired a temp to do our dirty work. She was an okay data entry person but terribly grouchy. She hated the fact that she was working in an environment of dodgy machinists and sweaty bikers and that the people giving the orders seemed to be young and goofy. To try to get her to lighten up a little and join the party, I utilized my favorite computer technology discovery—setting the control panel to play custom error messages instead of the standard beep. I turned the volume all the way up and recorded a message. The next morning everybody was treated to a speaker blasting swear words and curses every time she made a mistake. By the end of the day, she flipped out and stormed away.

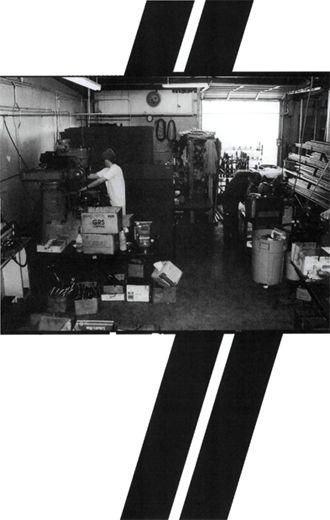

Hoffman Manufacturing. This is where the magic happens—the machine shop separated by a plastic wall. On the other side of the wall is the Secret Ninja ramp.

Adding the scores at BS comp in Oklahoma City.

The employee who usually made the most dramatic impression on everybody was Rocky. Rocky was our TIG welder, and he was a true craftsman. Every bead of every weld had to perfect. Physically, he was a sight: taller than an NBA forward, Rock weighed over two hundred and eighty pounds and sported long black hair and a bushy beard. He had been a Marine Corps demolitions expert in Vietnam but was discharged because even the Marines were spooked by Rocky’s passion for blowing shit up. Between his size, his dubious background (he’d been shot in the back, for instance], and his fiery temper, Rocky could intimidate anybody. It was sometimes hard to muster up the guts to give him direct orders. He had a problem with authority, and he was also impulsive—I deduced this after he told me he spent $19,000 on stereo equipment, despite the fact he lived in a tiny, run-down bungalow. He also drove a car that cost about $300, in which he’d installed a single modification—a brand-new, chrome-plated chain-link steering wheel that cost $400. But for all his quirks, Rocky was a master at his job. He personally welded about half of the entire Hoffman Bikes product output between 1992 and 1997. Our other master welder was Nate Charlson—normal by comparison, but still an artist with the torch. Between Nate and Rocky, we rarely got back any warranty replacements.