The Ride of My Life (17 page)

As a mother, she was the best. She supported all her kids in anything, regardless of how unconventional the idea, and looked at our successes as her own. I was the youngest and last child, so I got a lot of extra attention from her, which really made me shine.

By the time the tumor was found in one of her lungs, it was serious. She had an operation the same week and immediately began an aggressive chemotherapy campaign. The medicine made her sick for nearly a year, but after the months of treatment it looked like she was getting better. Throughout the ordeal, my mom never lost hope or let any of us feel sorry for her. To keep focused on the positive, she designed a dream home. She was going to beat cancer, she and Dad would build a great new place to live, and the Hoffman family was going to get on with life. The doctors were optimistic, and it appeared the disease was in remission.

After toughing it through a hard winter, just as the flowers began to bloom, Mother became really sick again. There was more chemotherapy. June stretched into July, and we all waited and hoped for a sign that she would be okay Nothing makes you feel more helpless than waiting. Some new tests were done, but she and my dad didn’t give us the details. Mom was always so positive; she never wanted to be a burden or make us worry. She and my dad encouraged me to do a weekend demo, so Travis, Steve, and I took the semi down to Ardmore, near the Texas-Oklahoma border for the shows. Before we headed out, Travis and I spent some time with Mom. We told her we’d see her on Monday morning. We left on Friday, June 17, 1990.

We made Ardmore around midnight but couldn’t find our hotel. We pulled into a strip mall parking lot for a map check. Suddenly, several police cars roared up with their lights blazing, surrounding the rig. My first thought was, “What did we do now?” I tried to remember if we’d avoided any weigh stations on the highway. Then my father’s business partner Rick Kirby got out of one of the police cruisers, and my heart sank, because I knew…. In the middle of the night, in the middle of nowhere, we found out our mom had slipped away.

Five days after the funeral, I was supposed to go on tour. I didn’t give a damn about my bike, or anything else for that matter. My dad told me I had to go—he wanted me to get on with my future, to keep my mind on other things, and to fulfill my commitments. I tried my best to keep it together, but inside I ached with a pain unlike any I’d ever felt before. There was a constant lump in my throat. I went on the road with Rick Thorne, Eddie Roman, Dennis McCoy, and Steve Swope, grateful for friendship during that tough time. My mom was in my thoughts every single day, and when I rode in the shows that summer, all the loss and loneliness I felt were channeled into my bike. I didn’t care if I got physically hurt because inside my heart was numb. Emotion poured out of me and took the form of bar hop tailwhips, 900s, and 540s with any variation thrown in, pushing eight or ten feet high. I started to scare my friends with my actions and my attitude. Every time I got on my bike I threw down everything I had.

The beautiful, the wonderful, the one and only Joni Hoffman. My mother.

In the fall of 1990 a European promoter brought me overseas for demos. He had a bad rep for stiffing his talent and had burned some bridges. I didn’t find out the scope of his shifty ways until after the trip, but I agreed to do a double demo for him. First, I’d make a TV appearance he’d lined up in Germany, and two days later I’d fly to England for a more traditional indoor half pipe comp with a demo afterward. The trip to Germany was fast and weird. I arrived wondering who was picking me up, where I’d stay, that sort of thing. It worked out in the end, and I wound up on a German variety show with Maxi Priest, the British musician. Our dressing rooms were adjacent, and when I saw his ornately braided hair, I thought he was Milli Vanilli. I yelled, “Hey, Milli!” and he gave me an evil look. The show ramp was sub-par, which only fueled my frustrations.

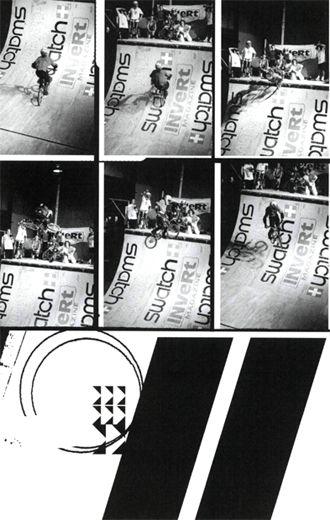

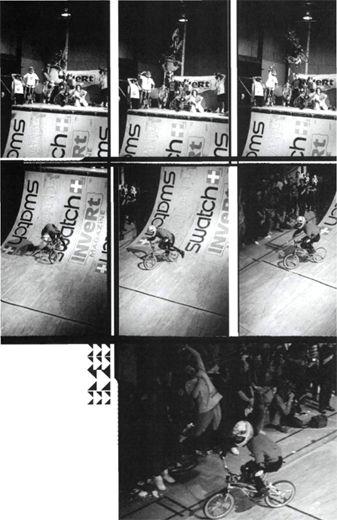

The contest in England was on a halfpipe that was pretty good. The ramp was solid and on my first warm-up run I pulled a 540 about eight feet out. The British love their twirling tricks, and so I strung an all-540 variations run together with a superhigh 5, into an inverted 5 on the next wall, into an X-up 5, into a no-handed 5. Then I gave the Brits a 900. They were pretty stoked, but there was really only one reason that I was going off. At the contest I met a little boy, about ten years old, named Matthew Jarvis. He had terminal brain cancer and had been brought there by the Make-A-Wish Foundation. His wish was to meet me. It filled me with sadness to see such a sweet, innocent kid facing his fate calmly. Being asked to ride for Matthew was the greatest honor I’d ever had. He only had a few days to live. During the demo I was crashing a lot, but I kept getting back on my bike—I hoped it wouldn’t break before I was through, because there was something I wanted to do. I’d never pulled a flair before and had been trying them for months. Deeply moved by Matthew’s presence, I dropped in for my last trick and blasted a big backflip and twisted it around 180 degrees. It was the first time I’d ever attempted a flair in public. I crashed hard, and the place erupted in swear words and cheers. My body and bike seemed operative, so I got back on and tried another. The second time I got off a good arch, landed it, and rode out of the flair; the first one I’d ever completely pulled. As pandemonium broke loose inside the arena, I rolled off the ramp and into the stands and immediately gave my bike to Matthew. It was probably the best reason I could imagine for pulling that trick for the first time. I would have done anything to make things all right for my brave young friend.

Losing my mother when I was eighteen messed me up for a long time. Our family began drifting apart, each of us finding our own ways to grieve and get on with our lives. The sport slipped into a recession, and it seemed like my entire world was changing, regardless if I was ready.

I lost my dependence, grew up, and started living completely on my terms all in a very short, intense time period. The one thing I felt I could trust was my heart—the thing inside me that my mom taught me how to use. I began doing things the way I thought they should be done, instead of listening to others or even to my own doubts. I questioned everything and was willing to risk whatever it took to find the answers. I wasn’t governed by anyone but myself. I became my own boss. I’ve never had another boss since.

TESTIMONIALA FLAIR FOR SPONTANEITY

Mat had his secret warehouse in Edmond, Oklahoma, and was like a mad scientist. He was so removed from the Southern California-based bike industry that, unless you were in his crew, you didn’t know what he was up to. I was announcing at the demo in Manchester the day Mat unveiled the flair in public. It wasn’t until just before he did the trick that he mentioned he had a new one. I was very excited and nervous. If Mat was going big with something new, it could end in a bad wreck. His first attempt, he pumped a few airs and hucked this big backflip and came in 180, landing it as an air. He crashed it, but that just added to the tension. His second try, he stuck the flair. What followed was the most spontaneous natural reaction that I’ve ever seen—I was totally blown away, as were the thousand-plus people in the building. I get goose bumps thinking about the magnitude of that day and that one trick.

-KEVIN MARTIN, KOV CONTEST SERIES ANNOUNCER AND TOUR MANAGER

A one-handed, no-footed candybar. This was at a 1992 BS comp at Stone Edge Skatepark in Daytona, Florida. (Photograph courtesy of Mark Losey)

H.M.F.I.C.

With the sport continuing its downward spiral, withering and shrinking, there were hardly any events or competitions left to attend. The thriving scene of the ’80s was gone. But freestyle was far from dead—it was just underground. From my perspective, I didn’t really have a choice. I needed a bike, I needed contests, I needed a community. In short, I needed to get off my ass and make it happen.

The companies that still made freestyle bikes didn’t seem particularly committed to, or even interested in, freestyle as a sport. They saw it as a number, and with the bike industry sales in decline, that number did not command much respect. In the past, I’d been offered a chance to have my own signature bike on Haro. I should have been stoked, but my

question everything

mind-set was provoking me to do a lot of soul-searching. If I was going to put my name on a bike, I didn’t want it to be at the mercy of bean counters. I didn’t want somebody’s lackluster bike sale stats to control who I

wanted to be. My lifestyle revolved around a sport of self-control, mastering the ability to adapt to weird environments. If there’s one thing I knew how to do, it was ride transitions.

I didn’t know dick about building bicycles, I just knew how I wanted mine to ride. I ransacked my Rolodex, making calls and asking questions of some of the manufacturers in the industry researching how stuff got built, and how to translate my ideas as a rider into bent and welded steel. I got ahold of Linn Kasten, one of the greats in BMX history. Linn is the guy who basically invented the BMX racing bike. He was in charge of the first awesome BMX bike company, Redline (who also had the first great BMX team). To his credit he had the creation of the first tubular forks, handlebars with a crossbar, and high-performance Flight cranks. It was an honor to have him help show me the ropes. I started planning the way any kid with a dream does, by scribbling my frame designs on paper. I went to Linn’s house where my crude drawings became intense technical discussions. We tuned the geometry in the drawing and discussed the dilemma of weight versus strength. I wanted a bulletproof bike, but it had to fly. There were incidents in the past where I’d broken three brand-new bikes in one day—and was sick of that crap. I wanted top quality, which meant using American-made 4130 aircraft grade chrome-moly tubing, the best money can buy. I was also stoked that it was going to be built in America, which was a rarity for freestyle bikes. A couple of weeks later Linn’s machine shop had built me five prototype Condor frames, one for Steve Swope, Rick Thorne, Dave Mirra, Davin Hallford, and me. Our mission was to try and break them. The Condor was good. It was quick, it was stiff, it had clean angles, but more than anything, it was built to last. I rode my prototype frame and fork set for seven months, trying everything in my power to bring it to its knees. The bike held up to flatbottom landings, rooftop drops, handrails, gaps, dirt, street, ditches, extreme weather conditions, name-calling, and giant ramps. I caused my body way more harm than my bike, and the rest of the prototypes held up, too. Midway through the testing phase, I made a couple of minor improvements and declared the design phase done. Time to see if the public would buy them.