The Ride of My Life (20 page)

The description sort of chose me, not the other way around.

Here’s a little Hoffman Bikes humor to sell product to dealers. This was for a postcard we mailed to our dealers that said, “Everything must go, but the helmet.” (Photograph courtesy of Adam Booth]

Candybar, at the Southsea Skatepark in England. (Photograph courtesy of Mark Noble)

HIGH ENOUGH TO DIE

It all began with a phone call from Hollywood in 1990. A research intern from the

Stuntmasters

TV show wanted to know if I could jump my bike over three burning cars. Yeah, I told him, I could do that.

Within a few days, I was whisked to Los Angeles to film. The stunt coordinator was Roger Wells, better known by his motorcycle moniker, Johnny Airtime. Johnny was an accomplished stuntman with a flair for the technical. His repertoire included stuff like launching his motocross bike one hundred and fifty feet off a ramp and landing in the back of a speeding pickup truck going fifty-five miles per hour. He did another jump over a speeding train that smashed through his takeoff ramp a split second after he was airborne. Johnny had it down—he was a physics wizard and a demon in the air. He’d prep for his stunts by calculating all the various variables, factoring in height to weight ratios, G forces, speed, wind resistance, tire pressure, what he ate for breakfast. He had never broken a bone in his body.

The stunt I had to master didn’t require much math; it was your basic pedal full speed, leave the ramp spinning (I’d decided to 360), and hang on tight. The distance was about thirty feet across, with a blind landing because of the smoke and intense heat from the burning cars. I was flown in a week early to practice and build up to the big leap. Within a few minutes of arriving on location, I was airing my bike over the ramp-to-ramp gap, having a good time. The producer saw what I was doing and called me over for a conference. He was worried that I wasn’t experiencing enough difficulty clearing the jump. He explained the importance of a dramatic TV buildup to my test of fire. For the next four days I had to fake like I was having trouble clearing the distance, and also fake a lot of deep personal contemplation while being documented by a film crew. The set was stationed in a hot parking lot out in the San Fernando Valley with nothing much around. This was my first taste of Hollywood.

On stunt day, I had to be on the set first thing in the morning to be wrapped in fireproof Nomex clothing, and go over the jump one last time before we rolled film. I was supposed to look as serious and nervous as possible. Instead I was dazed and totally giddy. The location had been moved to a nearby site so they could film with a lake in the background. The runway was downhill. During the practice runs there were no cars, and when they parked the cars between the ramps for the real thing, it stretched the gap to about forty feet. It didn’t seem as easy as it had earlier in the week. I was given a warm-up run before the cars were ignited, and on my first try the producer got his wish—it got dramatic. I overrotated my spin during the 360 and crashed. My back wheel turned into a taco. I was tired as hell, and now, beat up.

I was watching the jump site from about one hundred and fifty feet away—three times the runway that I needed—but the director wanted a camera in a truck to follow the shot and get a close-up of my expression and intensity. They also put a microphone in my helmet. “Let’s light the cars on fire!” said the director with nervous glee. With a demonic

whoosh

the cars burst into greasy flames, and I was given the cue to jump. I took my first cranks toward the target and started to chuckle. By the time I hit the ramp it was all-out laughter. There was a split second of terror as I twirled through the furnace, which I could feel even through the protective clothing. I landed the 360 perfect and touched down still cracking up. The host of the show rushed over with video cameras in tow, eager for a poststunt interview. The air was filled with the smell of burning tires and the sound of me laughing hysterically. I took a couple of seconds to compose myself, and I was greeted by the producer, who was chapped about my good humor ruining the dramatic tension of the moment, which made it even funnier to me.

The best thing that came out of the stunt, however, were the conversations I had with Johnny Airtime. We talked about something I’d dreamed of for years—a twenty-foot aerial on a bike. Airtime broke it down for me: The standard halfpipe height was a ten-foot-tall ramp with a

foot of vert. Hitting that transition at full pump provided about thirty miles per hour of speed and created a vertical speed of about eighteen miles per hour. This put about two and a half Gs of gravitational force on my bike and body. On an eleven-foot ramp, I could get about thirteen feet over the coping. Airtime reasoned that by applying that same formula toward a larger transition at a greater speed, it would be approximately the same amount of G forces—the critical factor that determines the way the air feels. “Just build a twenty-foot-tall ramp and figure out how to hit it going sixty miles per hour, and bingo,” Johnny said. “It’ll feel about the same as airs on a twelve-foot ramp.”

My mind was ablaze with possibilities as I boarded the return flight back to Oklahoma.

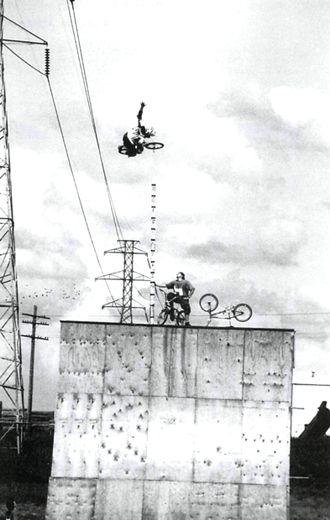

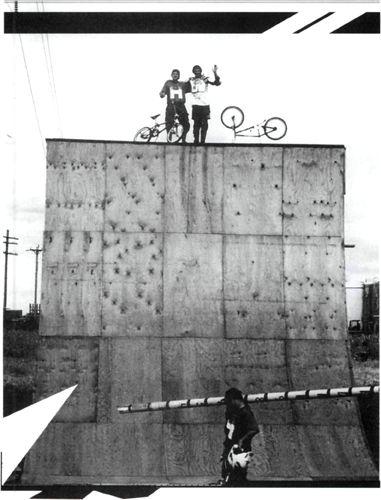

Half the battle in airing the first twenty-one-foot ramp was getting to it via this sketchy runway.

The stuff I know about riding, I learned one crash at a time. These are the things I have discovered by riding vert.

The secret is in the timing, the flow, and the rhythm. People mistakenly refer to vert riding as a very aggressive discipline. You have to be relaxed to truly flow on a ramp, and the only way to be relaxed enough is to build your confidence. It takes years of riding to master this game of staying physically loose in a very heightened mental state. Once you learn to flow, you start riding smooth and going higher. The higher you go, the more nervous you get, thus, the more relaxed you need to be because the more dangerous it becomes. If you want a new trick too badly, you can’t have it. You have to possess the confidence you can already do a trick before you even try it, otherwise you’ll be too stiff and probably wreck.

The goal is to land a fraction of an inch from the coping. That’s a perfect air. You pump as you ride down the transition, milking it for all the speed you can. String a few walls’ worth of perfect airs together and you go higher each time, the same way you pump to go higher on a swing set. If your wheels clip the top of the ramp on reentry, you’re in for some pain. Hanging up or casing your back wheel on the coping will make you flip forward and dive into the bottom of the ramp headfirst. Usually you wake up with a flat tire. If you’re paranoid about hanging up and pull out too far from the ramp during an aerial, you’re also in trouble. Landing too low on the tranny or in the flatbottom causes you to lose all your speed. If you bottom out hard enough, you can break bones or bike parts. And finally, if you come in too vertical and land low on the transition, you flip over the bars onto your head, thrown into the flatbottom like a lawn dart. Some people call this one a dead sailor. It’s notorious for knocking riders unconscious. Safety gear doesn’t make a vert rider invincible, but it decreases the pain potential. I wear kneepads, elbow pads, a chest protector, knee or arm braces to protect past injuries from worsening, and, of course, a decent full-face helmet. After being knocked out a couple times wearing the same helmet, the foam becomes compressed and it needs to be replaced or it won’t offer enough protection.

As time passes, you start to read ramps like a book. You drop in, and by the third wall you can draw a map in your mind of the ramp’s sweet spots and weak points. On ramps with a lot of inconsistencies, it’s always good to carry stickers and mark the danger zones to stay away from. It’s tough to ride a freshly painted ramp because it throws your depth perception off. A ramp needs some color and light variance so that you can gauge your landings and when to pump. This is why sessions at sunset get more dangerous as the shadows start stretching across the transitions. Tire marks are the best footnotes for identifying lines, or just marking wear and tear.

Ramps can be built out of just about anything, and I’ve ridden the spectrum: Some were kinked death traps made of street signs and scrap wood; others were pieces of incredible art. The surface layer plays a huge factor in the ramp’s character. Just as

James Brown knows what kind of wood a stage is made of by the way it feels when danced on, I can tell what I’m riding on by how it feels under my tires. Plywood is the most economical and one of the fastest surfaces. For skaters it’s too choppy against polyurethane wheels, but rubber bike tires absorb the irregularities of plywood, and since it is hard, it’s fast. Fast is good. A lot of European ramps are layered in Scandinavian birch plywood, which is the shit—seven layers thick and the hardest,

fastest ply you can get. Both skaters and bikers love Scandinavian birch. It makes you tingle when you ride it. The only problem is it’s about sixty bucks a sheet, approximately five times more expensive than regular plywood. Birch plywood in the United States usually comes from Canada, and you have to settle for five-layered wood, with more filler, which is softer and slower.

This was the day we finished building the ramp. Steve and I rode to the top for the first time. It was spooky.