The Ride of My Life (35 page)

For established expert and pro caliber riders, there were a lot of new opportunities to plug into sponsorships. There were big[ger] bucks at stake and global exposure on TV, the Internet, video games, cereal boxes. You could feel it on the decks—what was once a space reserved for riders, and maybe the occasional brotographer, was now real estate that required a laminated pass to access. It was now a world of cameras, and postrun interviews, and in-depth analysis of things, like Dennis McCoy’s fufanu reentry technique. It was so cool to see hard work and dedication paying off for the independent companies and riders who had dedicated their lives to a cause. It was also odd-several of the top riders bought houses with money earned off fingerbike sales.

One telling detail about the turning point from famine to feast could be observed by going out to eat with a table full of bikers. In 1993, the check would arrive at the end of the meal and everyone would root around in their wallets and half-heartedly chip in for the check; somehow the stack of cash would

always

be about twenty-five percent short of the bill. In 1997, the same situation usually resulted in the bill and tip being

overpaid

by about thirty percent—everybody wanted to flaunt their success and make up for the days of being broke.

Another thing I noticed was a dramatic increase in the number of people approaching me for autographs. It seemed as if everywhere, from the grocery store to the airport bathroom, I’d hear my name spoken and turn to see a fan with a pen. For years, I’d ridden behind the disguise of a full-face helmet and lived a fairly anonymous life. I’d been on more than thirty magazine covers, and nobody on the street knew I existed. After a few times hosting TV shows, people suddenly knew who I was and wanted me to sign stuff. It was like fame created merit, instead of merit creating fame. I’d be asked by people who didn’t know who I was to sign something for them, because they’d seen me signing an autograph for somebody else and instinctively knew I was somebody “famous”…

but who was I

?

It was weird. Cool, but weird.

Bikers were drawing unprecedented attention from a whole new fan base, many of whom didn’t even ride or skate. A lot of this attention was the direct result of hype, and marketing. Those signs you’d see people holding up in the stands during the X Games that said “Miracle Boy,” or “SPIN to WIN,” or, “John Parker 3:16” were often made by ESPN2 interns, who then “placed” the signs in the crowd. The network reasoned this colorful spectator support would help create a fan culture and give the action a familiar, TV-friendly appearance to viewers. They used to do it all the time with stick and ball sports. As long as there were plenty of active participants in bicycle stunt riding, it didn’t disturb me too much. What was hard to watch, though, was seeing the way a few riders became blinded by their own rising stars. TV had a way of converting natural charisma into a thing called an

image

. A few guys bit the hook and bought the hype and began to live up to the icon or nickname they had developed. I’d see dudes roll up to a session in flossed-out cars, boasting about blingbling spending sprees that covered everything from jet skis to jewelry. It’s hard to tell a friend who is skilled, successful, and enjoying themselves tremendously that they ought to slow down the frontin’, because they could be one knee injury away from a heap of credit card and income tax debt. And on top of it all, the injury would render them unable to do what really matters: ride a bike for the sheer enjoyment of it.

Medicine has the power to cure and the potential to become poison if the dosage is too high. I saw the benefits of TV coverage—we had saved the sport from near extinction, and TV was definitely helping usher in a new era of prosperity. For this I was grateful. Amid all the new opportunities to ride, get paid, travel, and get coverage, the very thing that was growing our sport was also threatening to alter its history. The sport came from driveways, parking garages, and backyards. It was kind of freaky seeing it in the surreal space of prime-time television. For the first time, the sport had a season, because all the contests happened in a compact timeline building up to the Summer X Games. I don’t want to snivel and moan about bringing a change I signed up for, but one thing I realized, in retrospect, was the sport was starting to develop a cycle of repetition. It was getting harder and harder for the voices from the underground to be heard or expressed, because they were overshadowed by the sport’s success. I’d put on a contest. Television (ESPN) covered the competition. Kids, because they were rarely exposed to riders who don’t compete, wanted to know more about the guys they’d see in the contest. So magazines understandably catered to their readership, by focusing on the “popular” riders. It seemed to be the same riders all the time because the choices were so limited. This, in turn, provided a shrinking perspective of our sport, making it difficult for a rider who didn’t become a part of the cycle to have an impact on the sport. Look at flatland riding—flatland is such a highly technical facet of bikes, it’s hard to understand the nuances unless you do it. It didn’t seem to get people fired up as easily as the lowest common denominator in excitement: big air and big crashes. So most of the coverage from contests ended up focused on dirt jumping, park riding, or vert (which, by the way, also gets shorted on magazine coverage). And the top flatland guys, all just as dedicated as any of us, made considerably less money for putting in just as much work.

When we have a battle between the Gene Simmons action figure and mine, my daughter Gianna always picks the daddy figure.

I was young and I needed the money. (Photograph courtesy of Adam Booth)

Heat is how the entertainment industry calculates the popularity-to-dollars potential of people, places, and things that are cool. Pop culture icons are supposed to be “cool,” which gives them “heat,” and the hotter the heat, the cooler one is perceived to be. But stuff that’s processed to be cool is usually lame. The

really

cool things are often not very popular, and in fact are considered lame by the mainstream—which is what makes the things cool in the first place. But if something is lame enough to stand out, it attracts other people with similar aesthetics, and a culture begins to form. Then this lame (but actually cool) thing that is underground heats up as more people discover it. Punk rock and action sports used to be considered lame, which was cool. Then they got cool, which is kind of lame. But I guess that’s cool.

Being a pro bike rider has still got to be one of the best jobs on the planet. But, like the saying goes, pimpin’ ain’t easy.

This was right after I figured this trick out at Woodward at the CFB finals.

THE COMEBACK KID

As the middle 1990s stretched toward Y2K, my riding ebbed and flowed through spurts of progress. Airtime was cut into by injuries, surgeries, recovery periods, and workload-related drama. I’d taken on a lot of responsibilities; keeping the bike company going full tilt, promoting Sprocket Jockeys shows, and running the BS event series and a TV production schedule put me under steady pressure. I was juggling and struggling to stay on top of it all and still keep focused on why I was spread so thin: I love being a bike rider.

One of the best perks about an occupation in action sports is travel. There’s a magic, invincible feeling being a stranger in a strange land, riding with friends who all rule. Walking into an arena in a country where you don’t even speak the native tongue, and hearing ten thousand kids screaming the universal language of stoked…and above the din, recognizing your name being chanted. It gives you chills, makes you feel alive and young. You want to try hard to be the invincible guy they think you are.

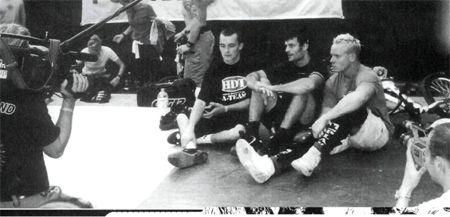

The 2000 World Championships, right after I won my tenth title. Simon Tabron, Kevin Robinson, and I got the top three spots.

From the start of my career, I racked up enough frequent flyer miles to get a free ticket to Jupiter. The irony: For the longest time, the only thing I’d see on most trips was the hotel and the halfpipe. If I was lucky I’d get a chance to street ride. Jaci convinced me to start making the effort when traveling to visit a museum or two and to embrace foreign culture as a truly unique aspect of my job.

When I was offered the opportunity to bring the first western riders into Malaysia for a bike stunt tour, I didn’t leap at it right away. Sitting in my office in Oklahoma, reading an E-mail talking about something called the Golden Dreams tour, I was a little skeptical. I didn’t even know exactly where Malaysia was on the map. The Golden Dreams guys asked me to assemble the very best riders in the world—often a sign of people who had no idea of the price tag for such a request. It sounded iffy, and I figured the promoter would recoil when they realized the costs associated with importing ten bikers and three skaters. I spat out a number off the top of my head: A twenty, followed by three zeroes, per rider, for seven shows. But the golden dream turned out to be real—a few weeks later our posse arrived in Kuala Lumpur, greeted by a wall of insane air pollution and superfriendly short people. Our first demo was in a stadium, so we went over to the check out the ramps they’d built us and found an incredible disaster—twenty-foot transitions cut down to ten feet tall—not the ideal big air devices we’d need. I got out the pen and a few sheets of paper and started scrawling. I handed it to the lead builder, who spoke little English, and asked him to see what was possible in twenty-four hours. I have no idea how many laborers they roped in, but we came back the next day and there was a street course and a vert ramp built to spec. We’d arrived thinking we could show up, strap on our gear, and get down. The Golden Dreams promoter pulled me aside before our first show and asked how our choreography was going to work with the DJ they had spinning our music. Uhm, choreography…

right

. I told him to hold that thought, while I called my crew of riders over for a quick huddle. In fifteen minutes we’d worked out a pretty tight show that went off without a hitch. This format was repeated for our shows throughout the remaining cities on the tour; we also got downtime to hang on the beach, eating omelets, getting sunburns, and acting like fools.