The Ride of My Life (38 page)

The second I left the coping I could tell I wasn’t going to ride away from it. That was the worst part, being powerless to alter the situation as I shot straight up past the twenty-, twenty-two-, twenty-five-foot hash marks on the pole. Fifty feet and change above the ground. At that height, it’s pretty insane to toss your bike and try to run out of it, so I held on, angled my bike to avoid hanging up, and came in crooked. I mentally braced myself to take the hit and landed way too hard. My arm, weakened after four rotator cuff surgeries, gave out and I nailed the ramp with a mighty spank. I don’t know if it’s a good thing, or a very bad thing, that I still don’t remember much of that day. The impact erased those memories—and all my memories—from my hard drive. Later, I could barely bring myself to watch the crash on video. It was bad.

When I hit, even the best helmet in the world could only do so much to save my head. My helmets are made by Simpson and are, bar none, the best head protection you can get. They’re the choice of pro stuntmen and NASCAR drivers and cost $450 and up. Mine was even custom-made, the ultimate armor with enhanced peripheral vision. As I piled into the ramp, my face shield exploded, and the jagged fragments tore my lip off. I was instantly knocked out, and as I plowed across the ground my body was dead limp. It took my friends and family about three minutes to revive me by screaming my name, afraid to move me for fear of spinal injuries. There were a lot of tears that day. An ambulance arrived and rushed me to the hospital, where I spent the day in and out of consciousness, and then another three days in a total fog, blacking out at random. Plastic surgeons put my face back together. A battery of brain scans and EEGs revealed more terrible news—my brain activity was all over the place, registering abnormal. My memory was wiped, and I was so dizzy I didn’t regain my equilibrium for nearly three weeks. The doctors said there was nothing they could do except treat the symptoms and prescribed a huge bottle of pills that I was supposed take every day for the rest of my life. The medication was definitely not an improvement; instead of balancing my brainwaves, the pills doped me up to the point where all my senses were blunted. Riding was not an option.

In all my years on a bike, I’d learned to diagnose injuries and had developed an internal sense of what was necessary to recover. But a head injury like this was impossible for me to assess—I’d damaged my brain and was unable to use the very tools I needed to gauge the extent of how badly I was hurt. I kept forgetting things and had no memories of vast chunks of my life. Jaci would mention something—like a trip we’d taken to

Japan

. “I’ve been to Japan?’ I’d ask, stunned. She’d have to fill me in on the trip, or show me photos, and something would trigger a vague memory, and I’d be able to mentally reassemble my experiences. As the weeks passed, my physical scars and injuries began to gradually heal. But there was a lot of emotional damage, too.

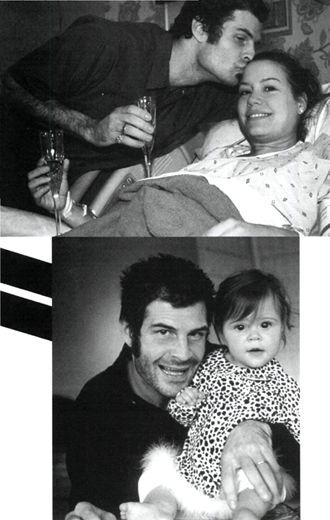

This little girl steals my heart. Baby G was born on December 19, 2000.

The people around me were worried for me, but they were also kind of pissed. I’d come damn close to taking myself out—twice. While everybody wanted to see me break my old height record, they wanted it because they hoped it would put an end to my obsession with huge airs. I don’t have a death wish; I have a life wish. I’ve always craved the experience of living at my potential—that has been the driving force behind every crazy thing I’ve ever done. The twenty-four-foot quarterpipe was part of that need, and for a long time I thought I’d never be able to top the feeling I got from fifty feet up. I was wrong.

One afternoon during my recovery, I was goofing around with our little girl, Gianna. She was only about four months old—since the day she was born she’d been basically a cooing, crying, gurgling little squishy thing wrapped in fuzzy clothes. But her senses were developing bit by bit, and that afternoon a change happened inside her, right in front of me. I made a face and a silly noise. Gianna looked back at me with a sparkle in her eyes, and for the first time ever I made her laugh. I did it again, and her reaction doubled—she cracked up, hysterically. This funny face game was repeated about five hundred times. It was so awesome. Her laughter and the look she gave me was the most precious substance. I think I changed during that moment, too. While my family and friends always had to accept me for who I was—a guy prone to high-risk activities—my daughter had never agreed to those terms. I brought her into this world, and I had a responsibility to be there for her. That feeling I got from her laughter was a high that overpowered even my love for pushing my own limits. It put a knot in my stomach to think I could’ve missed out on her first laugh. As I lay there with my nose pressed to Gianna’s, everything clicked.

It was time to leave the big ramps alone and be satisfied with what I had: Twenty-six and a half feet, and a little person who could always count on me.

“You win,” I said to Gianna.

“Bloo,” she replied.

Dialing down the center.

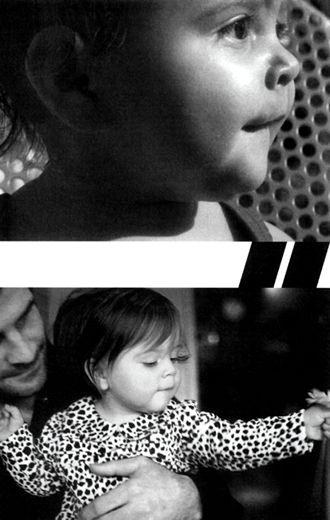

Flipping for a 1997 X Games commercial directed by Samuel Bayer, the same man that directed Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

HOLLYWOOD

The first time I met Johnny Knoxville he was a skinny joker known as PJ Clapp. That’s his real name. PJ was a writer/slacker who’d transplanted from Tennessee to Hollywood, eventually slipping into the commercial acting scene with his charming personality and jacked-up sense of humor. I think I’d seen him once or twice on TV before we actually met; he’d be holding a can of Coors beer looking stoked or eating Taco Bell nachos in a rowboat looking confused.

In 1996, PJ came to Oklahoma to do a commercial to promo the X Games. The theme of the commercial was PJ pretending to be a laser-guided supergroupie, driving around the country in a car and hitting up all the hot bike and skate spots on an odyssey to find athletes. He was going to sneak into the Hoffman Bikes warehouse and steal some T-shirts. The HB crew and I were supposed to chase PJ through a field and kick his ass.

We did.

The next time I saw the T-shirt PJ had snagged from the warehouse, it was a year or two later. PJ was wearing it while waving a gun around, a nickel-plated .38 snubnose revolver, as a shaky-handed videographer documented him in some remote location. It was the most gripping scene in the second

Big Brother

magazine video,

number two

, and PJ was about to “field-test” a Kevlar vest. He set up the scenario by suiting up with the vest, then tucked a slim stack of porno mags underneath the shirt, for extra armor. PJ scrawled a circular target on the shirt with a marker, then he stuck the gun in his ribs and pulled the trigger. The .38 slug could’ve easily gutted him, and PJ had no idea if his stunt would work until the moment of truth. The bullet blew a smoking hole through the cotton and left a deep dent in the Kevlar and a giant bruise on PJ’s concave chest. But the vest did its job and saved his life, and the insane act topped a long list of totally unbelievable moments in action sports videos. It would later become the shot heard round Hollywood.

Fast-forward about a year: I was in LA for the E3 convention—an electronics and video game industry trade show.

Kelly Slater, Shawn Palmer, Tony Hawk, and I had all

signed deals with Activision. It felt pretty cool to be handpicked alongside such legends, and each of us had a video game coming out to represent our sports. Before the trade show, I was sitting around the hotel, bored. I gave PJ a call. “What have you been up to?” I asked. He cackled on the other end of the line. “We’re coming over to show you,” he said and hung up.

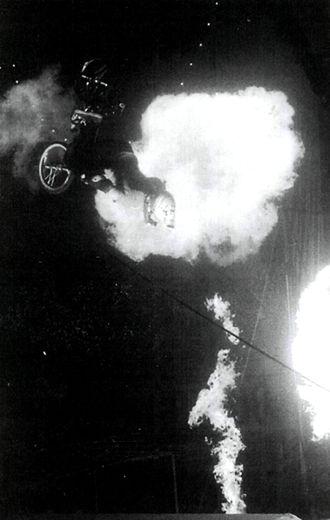

These were the proposals I sent to the MTV’s Senseless Acts of Video show. Hell yeah!

A second later he called back, to get my room number, then hung up again.

In the months that had transpired since the

Big Brother

video premiered, PJ and friends Jeff Tremaine (

Big Brother’s

art director; old school readers of

Go: The Rider’s Manual

may remember Jeff’s name) and Spike Jonze (also a

Go

alumni) had been busy. When PJ and Jeff knocked on the door to my room that night, there were holding a VHS tape—the product of their labors. They were calling it

Jackass

. The tape was popped into the VCR, and the TV screen lit up with a barrage of homebrewed street skits involving fire, trampolines, weapons, self-induced animal attacks, clowns on stilts, bad driving, vomit, shit, midgets, pranks, and farting. It borrowed from the best of

Big Brother

magazine and skateboarder Bam Margera’s infamous

CKY

underground pranks video. The Jackass run-and-gun digital video style was documentary/reality TV taken to a new level. It was, in a word, hilarious. It was also a little like watching a car crash—you wanted to turn away, but… couldn’t. After the tape was finished, PJ and Jeff both had stupid, triumphant grins on their faces. They were going to try and sell it to a TV network but didn’t know how or who quite yet. “That would be the best show on TV—

if

you could get it on TV,” I said, still laughing. We decided to head downstairs to the hotel bar and have a beer. Or two.